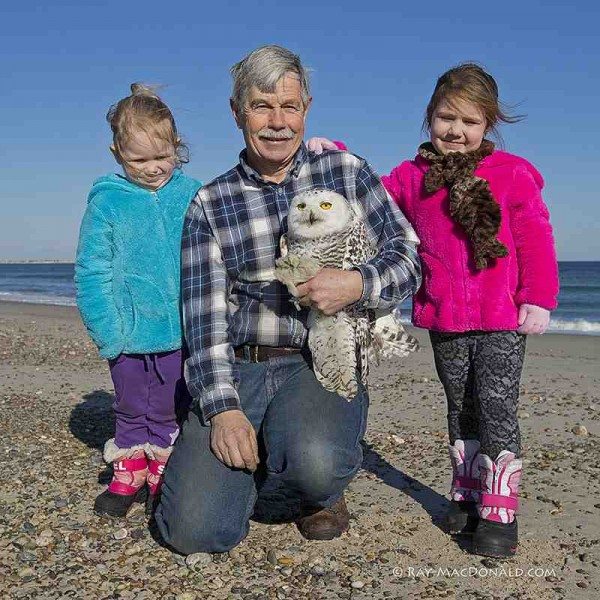

With his granddaughters Gabby and Alexa by his side, Norman Smith releases a banded snowy owl, relocated from Logan Airport in Boston, a few days before Christmas. (©Ray-MacDonald.com )

There’s been a lot going on behind the scenes at Project SNOWstorm since the beginning of the year — though not always the working out the way we hoped or expected, which is often the way things go with wildlife. Here’s an update on what we’ve been up to.

* * * * *

We continue to track the movements of our returnee owls, Dakota, Baltimore and Hardscrabble — although that last bird, Hardscrabble, has been off the grid for the past week and a half, in an area with poor cell reception about 100 km (60 miles) west of Ottawa, ON.

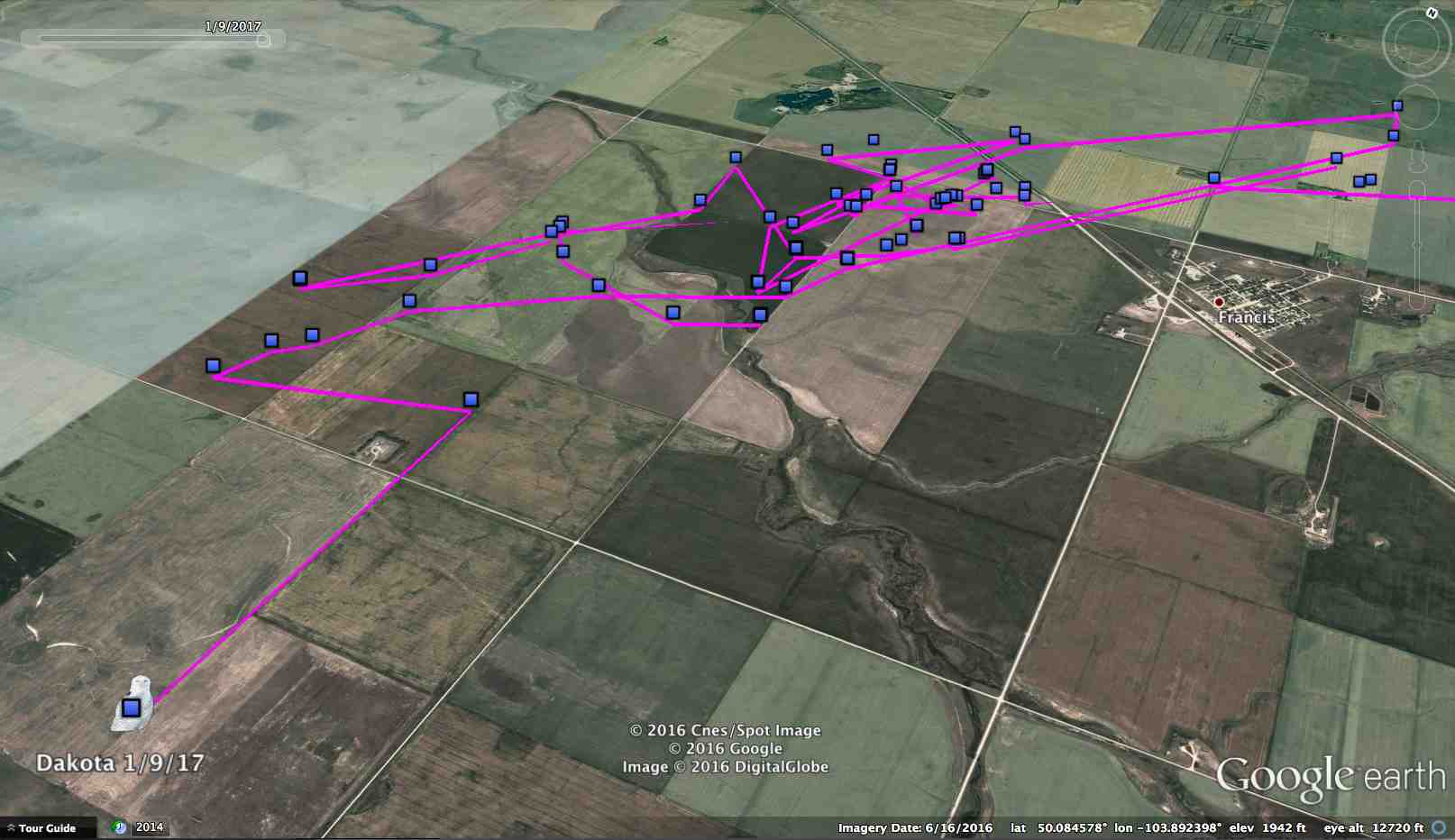

Dakota seems to be finding southern Saskatchewan to her liking, and remains near Francis, SK. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Dakota remains in the same general area around Francis, Saskatchewan, where she’s been since the beginning of December, using an area of about 19 sq. km (7.5 square miles).

Baltimore has been more interesting. You’ll recall that when he first checked back in Christmas night, he was in the same neck of the woods as Hardscrabble. Then he moved down to Amherst Island on Lake Ontario, where he’d spent last winter.

To our surprise, though, Baltimore quickly moved about 130 km (80 miles) northeast, and since New Year’s Day has been near the town of Kinburn, ON, close to the Ottawa River and near the Trans-Canada Highway (though staying away from the busy road).

Our friends Dan and Patricia Lafortune, who had previously been checking on Hardscrabble, have been keeping an eye on Baltimore for us, and have gotten some photos of him.

Look carefully — the tiny white bump on the top of the billboard is Baltimore, on a frigid daybreak in southern Ontario. (©Dan and Patricia Lafortune)

Baltimore’s transmitter is just visible above his feathers as he flies to a new perch. (©Dan and Patricia Lafortune)

We did have a hiccup with retrieving backlogged data from both Dakota and Baltimore. On Jan. 1, for reasons that aren’t clear, their units jumped over the stored summer and autumn data they hadn’t yet sent, and began transmitting current location data. In Baltimore’s case, it left us hanging with his movements last spring, when he’d flown up the east coast of Hudson Bay and made a big, puzzling U-turn in late April at the Belcher Islands, turning back and flying south 330 km (200 miles) to the midpoint on the eastern James Bay. In Dakota’s case, the data skip left us partway through July, with her still incubating her brood in Nunavut.

The problem was most likely a glitch caused by a combination of still-low battery power and poor cell signals, and we have every reason to assume we’ll get the data once their respective transmitter voltages build up sufficiently. (Our colleagues at CTT, which makes the transmitters, have worked up some software patches to smooth that process.)

In the meantime, we’ve updated their maps to include the partial spring/summer data, as well as their recent movements. Once we get the rest of the backlogged data, we’ll let you know here, and post that on the mapping pages as well.

* * * * *

Naturally, we’re not just resting on our laurels. We’ve had teams in several states banding and trying to tag additional owls.

At Logan Airport in Boston, Norman Smith has trapped and moved nine snowies this winter, all young birds, and all in good body condition. But despite his best efforts, two other snowies have already been killed: a juvenile owl hit by jet-blast, and a second-year bird that was killed in a plane strike — unfortunately, the latter an owl Norman had banded and moved last winter, and which had returned this year.

Norman and his granddaughters, just before the big female owl knocked down photographer Ray MacDonald. (© Ray-MacDonald.com )

Just as Norman included his daughter and son in his pioneering snowy owl work many years ago, he now regularly includes his adventuresome granddaughters, Gabby and Alexa. Local photographer Ray MacDonald (who has generously provided many of his photos to SNOWstorm over the years) was on hand last month when Norman and the kids released a big female at Duxbury Beach, Mass.

“This was owl was a big, aggressive girl that weighed in at 2,412 grams,” Norman said — about 5.5 pounds.

One of SNOWstorm’s focuses is working with airports and federal APHIS Wildlife Services to keep planes and owls apart. Last week, John Wood from Maine Wildlife Services was trapping snowy owls at Brunswick Executive Airport (where we tagged Brunswick last winter). John caught a beautiful juvenile male, but at about 1,400 grams the bird, though perfectly healthy, was a bit too small and light for our collaborators at Biodiversity Research Institute to feel comfortable giving him a transmitter. (Our guidelines call for the unit, harness and band together to weigh no more than 3% of the bird’s mass. The total in this case would have been about 3.5-4%.)

A few nights later, CTT founder Mike Lanzone caught another young male in Stone Harbor, NJ — and although it was a bit heavier, like the Maine bird that one was also a bit too small for our tastes. Meanwhile, plans to trap a bird on Assateague Island in Maryland on Saturday were scuttled by the big coastal snowstorm that hammered the South and New England.

Out in North Dakota, USGS biologist Matt Solensky, who tagged Dakota last year, has been stymied by repeated heavy snows, biting cold and lots of drifts. “Let’s not make it sound like I’m Sir Edmund Hillary, though,” Matt told me. “I’m just driving around in a heated truck, with the game on the radio, looking for owls.”

The drifts are the biggest challenge. “They make the landscape look like there are hundreds of owl-shaped things out there, all of which need to be closely examined,” he said. Matt suspects there are fewer snowies than usual in his part of eastern North Dakota this winter, because of freezing rain that fell Christmas Day between two heavy snowstorms.

“The hard crust on the snow and the packing nature of the strong wind, combined with the depth of the snow, has likely made small mammals quite inaccessible,” Matt emailed. “I’ll keep at it though. It would really be interesting to see how big their range is during a year like this. North Dakota is a poor host this year!”