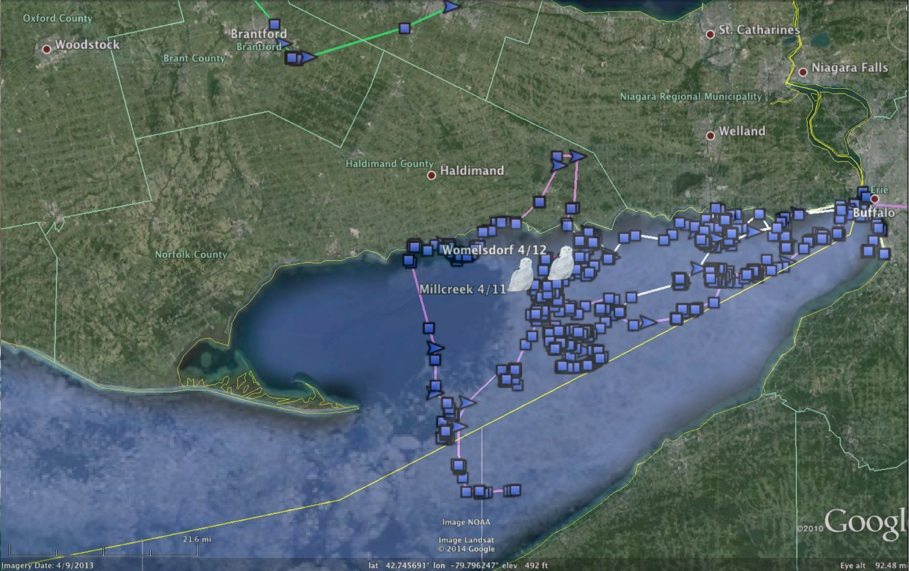

Womelsdorf and Millcreek are both haunting the edge of the shrinking ice sheet on Lake Erie. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth; MODIS imagery from NOAA CoastWatch)

A quick update on the latest data downloads from the past few days, mostly transmissions from April 11 and 12.

Millcreek and Womelsdorf were in fairly close proximity on the fast-shrinking ice of eastern Lake Erie. This combination image of the April 12 NOAA satellite image and their movement tracks show that they’re hanging near the ice edge — good hunting, presumably. Millcreek’s tracks are white and Womelsdorf’s are lavender, though at this scale the many location icons make it hard to see the tracks themselves.

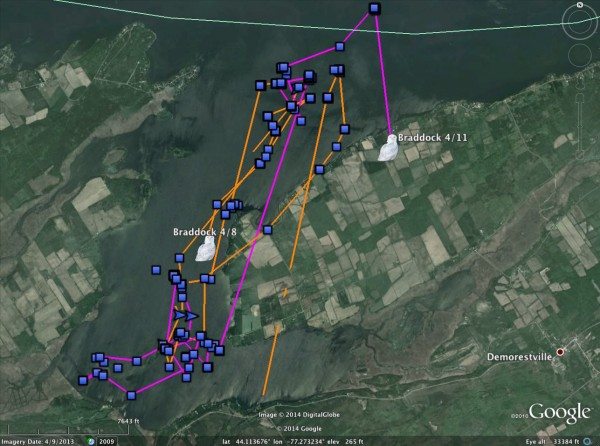

Braddock’s latest movements (purple) and his tracks from April 8 (orange) (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Braddock remained on the northern side of Prince Edward, Ontario, much where he’d been leading on April 8. Earlier this winter he split his time between land and ice, but he’s been sticking to ice lately — though you can understand why when you zoom in. All those nice, flat fields on Prince Edward are actually bracketed by wooded boundary lines every couple hundred meters, which would make a snowy owl feel badly hemmed in.

Kewaunee is still off the mouth of the Oconto River in Green Bay in northeastern Wisconsin, about 16 miles (25 km) from the Michigan line. Clouds have prevented any ice imagery there the past few days, but that area was still pretty solidly frozen last week. Given that he spent the winter just a few miles from Lake Michigan but never spent any time along the coast, it’s interesting to see him focus so completely on ice now that he’s moving.

Amishtown remains in a commercial/industrial area along the north shore of Lake Ontario near Whit by, Ontario. He spends his days on some of the big buildings, then moves at night to the lakeshore, making hunting forays offshore and along the beach.

Oswegatchie can’t seem to make up his mind. Having moved about 30 miles (50 km) north from Ogdensburg, NY, by April 8, he turned around, flew back to town, then flew 50 miles (80 km) back north again by April 11. That’s not unusual behavior for a bird getting the migratory itch — it may be that premigratory restlessness that the Germans call zugunruhe, which we’ve mentioned in the past.

So what about the owls that aren’t updated here? At the moment, we’re not shielding the location of any owls (beyond the normal three-day delay we impose on posting updated maps). Some of the snowies have been off the grid for just a cycle or two, but there are several that have been missing in action now for many weeks.

All we can do is speculate — either their transmitters failed, or they came to a bad end. Monocacy is one we have a bad feeling about; she was hunting one of the densest urban centers in the country in Baltimore, and electrocution (which would probably knock out the transmitter) is an ever-present danger. Nor is it an urban danger only. A colleague of mine in Maine reported watching a snowy accidentally electrocute itself over the weekend, landing on a too-small electrical insulator.

In some cases, we’ve tried to locate missing owls. Tom McDonald did a search for Cranberry in March, checking the area where he last checked in Feb. 15, but without success — and with a three-day call-in cycle, Cranberry may have moved far, far away from that point before something happened, including the middle of Lake Ontario. As the hunt for Plum showed, it can be hard to find a dead owl even when you have a precise location.

In a few cases (Buena Vista and Assateague being good examples) we’ve continued to have sightings even when a balky transmitter wasn’t sending us data as regularly as we’d like. But in most cases, the birds simply disappear, which is obviously frustrating — even though it’s going to happen with any wildlife-tracking project, and we knew it was inevitable when we started.

Finally, as I mentioned in the last update, now that many of the owls are within a few hundred miles of the limit of the Canadian cell network, a single night or two of flying could take them beyond cell reception — meaning we won’t hear from them again until they come back south in a subsequent winter. But since the main point of the study was to document their wintering ecology and movements down here, what we get now is really just gravy. The trove of thousands of incredibly precise, 3D locations and movement that we gathered this winter is a bonanza, which we’ll be starting to analyze in the weeks ahead.

7 Comments on “April 14 update”

thanks for all the updates. This is so fascinating! I appreciate all the maps and photos and information about these magnificent creatures.I feel bad for the ones that didn’t make it :-(but I’m happy and excited for the ones continuing their journey :-)I hope the lost owls reappear eventually but even if they don’t, so much has been learned from them already. Are you planning to continue this study next winter? There probably won’t be so many snowies migrating but I’m sure there will be some to track! also just wondering if the snowies travel further when there’s a full moon?

We’re definitely going to continue SNOWstorm next year. We won’t see a huge irruption of young birds, but there will be a normal movement of primarily adult snowies into their typical areas along the Northeast coast, Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley. (And with luck, one or more of our tagged owls will be among them.) Coincidentally, this week almost all the collaborators in SNOWstorm are gathering (in person or via Skype) here in Pennsylvania for a planning session to look at our next steps, including getting the many samples we collected analyzed, and preparing the results of our work this winter for publication. One of the biggest issues on the table will be where SNOWstorm goes from here — and we have some really exciting possibilities to weigh and consider.

What happened to Duxbury?

Duxbury is one of the unknowns I mentioned in the update. The last transmission we had from her was March 14, containing 63 locations from Feb. 27-28. The last known location was the roof of the big Necco plant in Revere, Mass., at 2:37 a.m. on Feb. 28. The voltage reading showed a dramatic drop off thereafter, and the unit had just enough juice to send the partial transmission two weeks later. We don’t know what happened, but the most likely explanation was that Duxbury was killed at some point after leaving the plant, and was lying on her back, blocking the recharge from the solar panel.

Will they outgrow their transmitters?

Fortunately, that’s not a concern with birds, which are basically as big as they’re ever going to be when they leave the nest — unlike mammals and many other vertebrates, they don’t have a long growth period. The Teflon ribbon harnesses we use have some room in their fit to accommodate the kind of seasonal changes in weight that birds undergo, but we don’t need to worry about owls outgrowing their harnesses.

wow! when i look at my email first thing i get really excited to see your posts; particularly, enjoying the detailed explanations. i effusively thank you guys! question: do any of you participate in any other birding studies we could follow throughout the year?