Becca McCabe releases our newest tagged snowy, an old adult male we’re calling Hochelaga. (©Rebecca McCabe)

It’s been a cold winter across much of central and eastern North America, especially the regions where we have tagged snowies this year, from the northern Great Plains to eastern Canada. But that’s changing, with some dramatic warming underway, and we’re already seeing the start of the spring migration — with one owl in particular that’s made a big leap north.

We also have a new snowy to add to the roster, only the second newly tagged owl of the winter — a lovely old adult male with a fondness for the Montréal airport.

Falcon biologist Julie Lecours with Hochelaga after the old male was caught — almost five years to the day after he was first banded at the Montréal airport. (©Julie Lecours)

We’ll start with our newest recruit, which was trapped by biologist Julie Lecours of Falcon Environmental on March 2 at the Montréal-Trudeau International Airport. Julie immediately realized the bird — a pure white male — was already banded, and records showed Falcon had originally trapped him at the airport on March 4, 2016, by which time he was already mature and almost completely white.

We normally avoid tagging new owls so late in the winter, because our main focus is studying wintering movement ecology and the spring migration is coming up fast. But tagging an old, experienced adult with a history of returning south is good investment, even if this bird migrates soon; he’s a proven survivor, and chances are very good he’ll be back in future winters.

In keeping with our normal nickname protocol, which uses local place names or geographical features — and with helpful input from the Falcon crew — we dubbed this bird Hochelaga, the name (as passed down through French) for the original Iroquoian village at what is now Montréal.

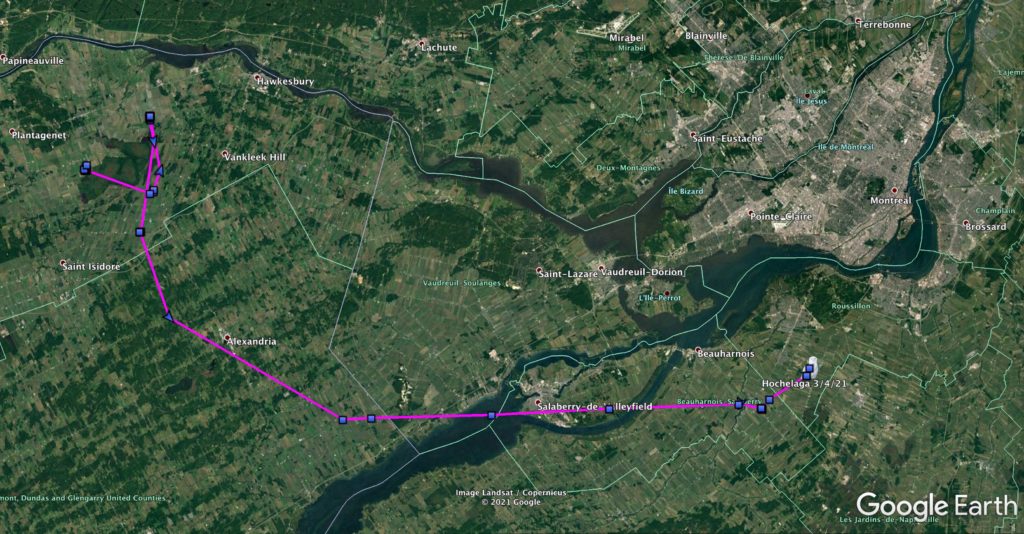

Owl or boomerang? Hochelaga makes a beeline back toward Montréal. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Hochelaga. (©Rebecca McCabe)

Hochelaga also provides another source of data for Becca McCabe’s PhD research on airport relocations, testing how altering the direction and distance of the relocation affects the likelihood of an owl returning to the airport. She moved Hochelaga a long way, 90 km (55 miles) to the northwest, releasing him in farmland near Alfred, ON. And…he immediately began moving back toward the airport. When Hochelaga checked in Thursday night, March 4, he was just 20 km (12 miles) across the St. Lawrence from the airport, closing in on what is obviously his favorite wintering spot. If he does return to the airfield, Julie and her Falcon colleagues will try to trap him yet again — they added some temporary blue dye to the bends of his wings before his release so he’s easily identifiable at a distance.

We’ll have a map for Hochelaga posted in the next few days.

As for the other owls, Yul and Alderbrooke remained last week where they’ve been all winter, east of Montréal in farmland on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. We had a report Friday of a snowy owl struck by a car near Alderbrooke’s last location; we don’t know if it was her, and the report came after her last data transmission of the week on Thursday night. We hate to see any owl hit by a car, but we’ll be crossing our fingers that tonight’s regular check-in has good news for us, and that she wasn’t the victim.

Dorval remained in Ottawa at last report on March 2, although a day or two later, the folks at Predator Bird Services think they spotted her at the Ottawa Airport, which she’s been avoiding most of the winter. She didn’t check in Thursday night but her transmitter battery has been limping a bit and might not have had enough juice. Simcoe, after spending many days drifting on ice on Lake Ontario (up to 65 km [45 miles] from her winter base on Amherst Island), moved back to the island as the ice broke up and has remained there ever since.

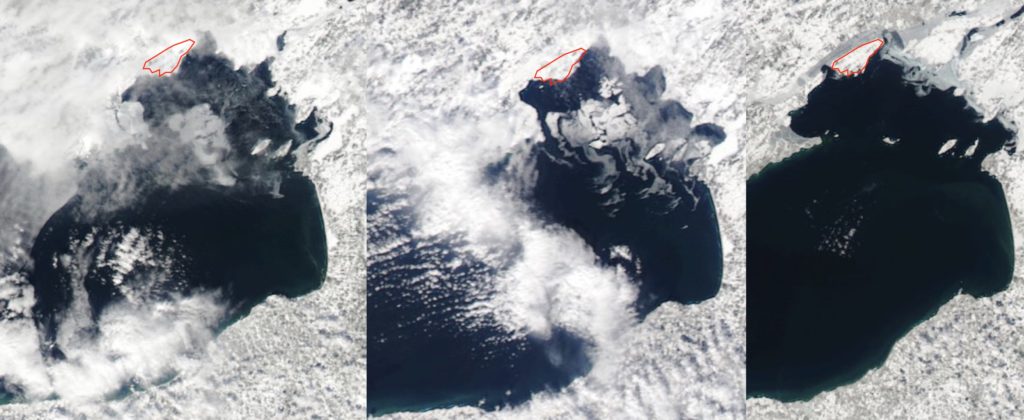

This series of satellite images shows how rapidly the ice broke up on northeastern Lake Ontario from Feb. 17 (left), to Feb. 21 (middle) and Feb. 26 (right). Amherst Island is shown in red. (NOAA CoastWatch imagery)

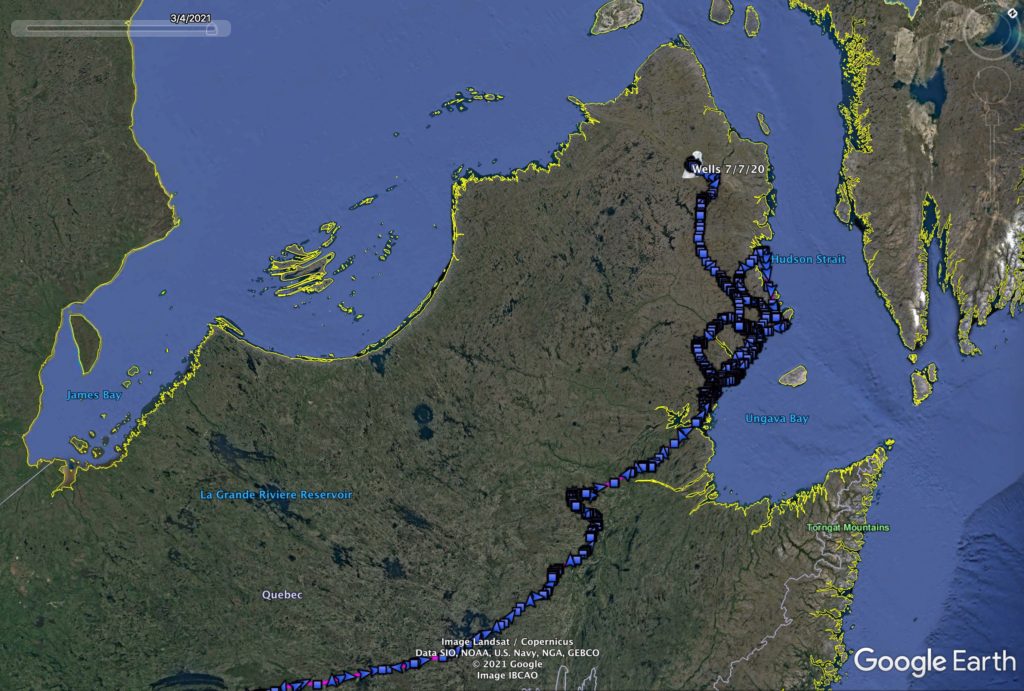

As her battery recovers, we’re getting more and more of Wells’ backlogged data, including these tracks from April-July 2020. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Wells surprised us last week with a large dump of backlogged data, everything from her departure north in April through early July. We can now say that she appears to have nested last summer in the northern Ungava Peninsula, where a number of other tagged snowies bred last year. (Ironically, we’re still not sure where she is currently, other than somewhere in southern Canada based on the cell network through which she connected. But with longer days and brighter sun we’re hopeful her old battery will continue to recover and we’ll get all of her stored data uploaded and caught up to the present time.) Here’s a map showing all of her movement since she was originally tagged in Maine in 2017, including the four summers during which we’ve followed her:

Four years’ worth of data, including four summers (as shown by dates) for Wells. (©Project SNOWstorm)

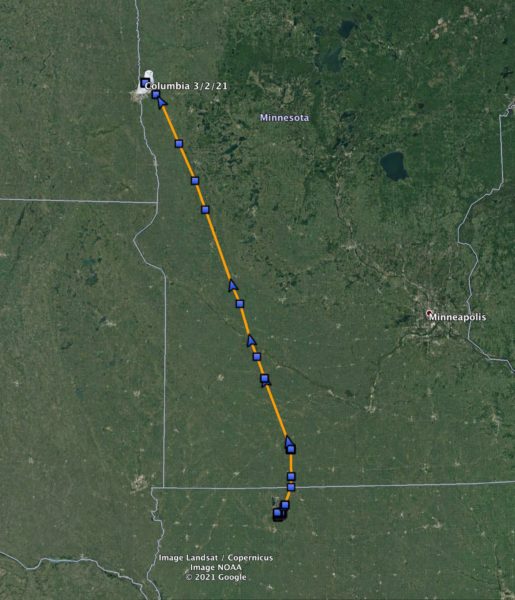

Columbia made the most dramatic migration this past week, leaving her winter territory in Iowa and bolting north. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Out on the prairies, all three of our tagged snowies have been moving north, none more dramatically than Columbia. This owl spent the whole winter in a very restricted area of northwestern Iowa, but on March 1 she started flying north, and by the next day she’d flown 267 miles (430 km) up through western Minnesota to just north of Fargo, though still on the MN side of the border. She hasn’t checked in since, which may mean she’s already moved into poor cell range in Manitoba, because her battery voltage was quite strong.

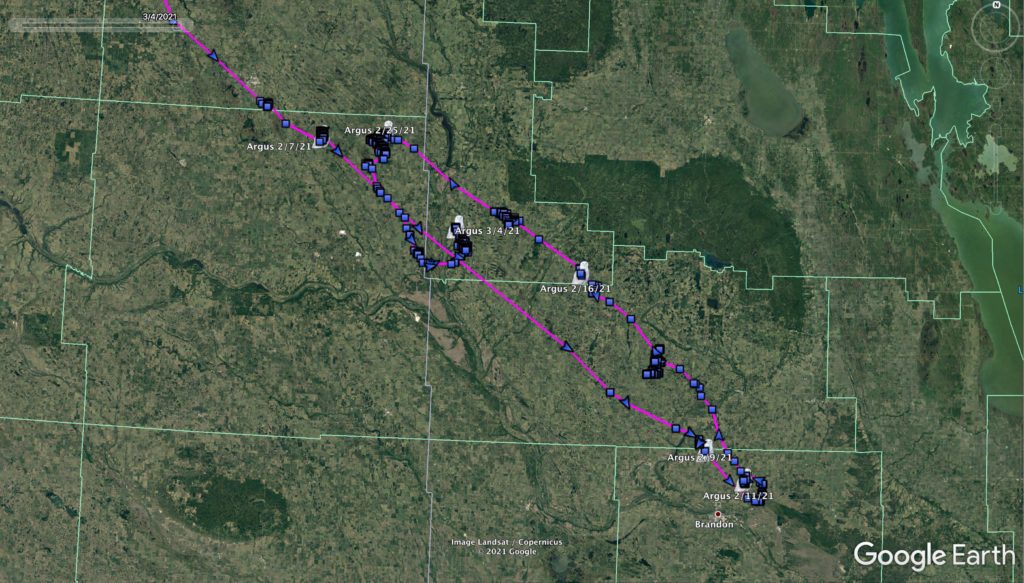

Stella continued her season-long movements, leaving northwestern North Dakota and checking in March 3 from just south of Lampman, Saskatchewan, in the extreme southeastern corner of the province. About 200 km (125 miles) to her northeast, Argus seems unable to make up his mind — he’s doubled back on himself a couple of times in the past month, moving in a narrow band between SK and MB, near Riding Mountain National Park in western Manitoba.

Argus really can’t seem to make up his mind: North or south? East or west? Saskatchewan or Manitoba? (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

21 Comments on “A New Face (and the First Stirrings of Spring)”

Columbia flew 267 miles in one day. Wow! The photo of Beca releasing Hochelaga is beautiful! Thank you for another update.

I photographed a gorgeous nearly pure white Snowie last weekend on the northern end of Pt. Peninsula, Jefferson county, New York…. he was magnificent! He was the only one I saw all day!

Last year I photographed 7 Snowies on Pt. Peninsula in day day…

Hello. Can you tell me the attraction the owls have to airports? In particular in the northeast? You never mention owls in other areas and airport. Thanks.

Kevin

Kevin, we assume snowies like airports because they look (a little, at least) like home — they are flat, open and treeless, a bit like the wide horizons of the Arctic. And airports are often the only open habitat in urban and forested areas. Add to that the fact that while there are lots of vehicles, including airplanes, moving constantly around airports, there are relatively few humans on foot, especially out near the runways, taxiways and large grassy areas that surround most airstrips. Many wild animals become easily habituated to vehicles, and snowies tend to be fairly trusting anyway, especially young individuals. Finally, airfields usually have a lot of owl food, either in the form of abundant rodents and other small mammals in the fields and grasslands, or proximity to large bodies of water with plenty of waterbirds.

I forgot to make clear, snowy owls do show up at airports across their winter irruption range. Our association with a number of airports in the Northeast, including Montréal, Ottawa, Logan in Boston, the Portland Jetport in Maine, etc., has more to do with where we have colleagues and partners than where the owls are. Our friend and SNOWstorm co-founder Norman Smith, for example, has been working with snowy owls at Logan since 1981.

I am very intrigued by how much some of these individual owls move around in the Arctic during the summer, and between years. It concerns me, though, that it might suggest that there are fewer of them than we might think…

Allen, you’ve hit the nail on the head. Until about 10 years ago, the global population estimate of snowy owls was about 300,000, based on simply adding up maximum numbers in different regions around their circumpolar breeding range. But telemetry work on the breeding grounds by Laval University in Canada, Denver Holt in Alaska and researchers in Russia and Europe showed that snowies may move thousands of km between breeding seasons. So Eugene Potapov (an early SNOWstorm member) and Richard Sale did a more careful analysis in 2012 taking that nomadism into account, and concluded the global population was an order of magnitude lower: about 30,000 owls. (This has been misinterpreted to mean that snowy owl populations have declined significantly. In fact, no one really knows what their global population trend is.)

Speaking about airports I can walk to Bradley International Airport where I live in Windsor Locks, Ct so when I was shown a photo yesterday of a Snowy owl taken there I was like O M G wish I had known about it! Of course when I showed up to look for it I turned up empty handed. I did however find a Rough Legged Hawk as a nice consolation prize!

How do you determine if there is enough prey in the places you are relocating the owls? Seems like that would have the most bearing on whether the owls stay on their relocated habitat or not. It would seem foolish to relocate an owl again to a habitat that may not have the needed resources to sustain the owl.

The fact is, we can’t. We do pick habitat that *ought* to hold plenty of prey — grasslands, farm fields and pastures, coastlines. But small mammal populations rise and fall cyclically, and what’s a hotspot for prey one year may not be the next, even though to a human eye the habitat looks exactly the same. The presence of lots of other raptors can be a tip-off that the hunting is good and prey are abundant, and the area in which Becca release Hochelaga has lots of diurnal hunters like red-tailed and rough-legged hawks; we’ve also targeted release sites with other snowy owls. But that’s a double-edged sword, because that also means more competition and harassment — raptors don’t play well with each other, and territorial redtails (to take one example) may harass a snowy owl mercilessly. Female snowies will also dominate smaller males. So we make the best judgement we can.

Hi

We tagged Columbia at Madison Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary near Arlington, WI on Jan 28, 2020 and have been following her frequently. As Scott mentioned today she was just northeast of Fargo on March 2nd. Columbia left Fargo on March 2nd after 7:00 p.m. On March 3rd she stopped at Glenn Slough a few miles north of McVille, North Dakota. The exact area she spent a few days at in late March of 2020. As of 7:00 p.m. tonight (CST) she was 235 miles northwest of Fargo and a few miles northwest of Souris, North Dakota, and only a few miles south of the Manitoba border. Amazing data. We wish her well and hope she returns next winter.

Mark and Susan Foote-Martin, resident managers, Goose Pond Sanctuary

Thanks, Mark and Sue — you guys have been a great help for years, and we appreciate it and your enthusiasm. All the owls checked in Sunday night, a few hours after I posted my update, and Columbia continues making tracks north.

My favorite owl Stella, flew within 15 miles of my house, as she quickly exited North Dakota on the evening of Feb 14th. “Hi Stella!” Her wandering this winter is so unlike her past winters. Is there any chance that she could be searching for a mate? Could this be the summer when she raises her first family?

Just love reading their flight patterns and where they decided to settle in the winter months. Has anyone tried to band the one at Burke Airport in Cleveland, Ohio. We always seem to get one there every winter and there was a sighting at Maumee Bay State Park earlier. Thank you for sharing your data.

A few years ago I was in Ohio attempting to trap a large female for tagging, but she was smarter than me. We’ve worked with our colleagues at Black Swamp Bird Observatory (a shout-out to Mark Shieldcastle) to tag owls like Buckeye caught at Detroit’s airport, but we don’t have anyone on the ground in OH with the permits and training for regular trapping.

I was lucky to capture some nice images on March 5 at the Montreal airport of a beautiful male, after sunset. On Sunday March 7, another lucky day with two females in approximately the same spot.

It’s disconcerting to read that these birds are in decline. Each time I read a new posting, I gain more and more respect for these owls. I will miss seeing them on the shores of Massachusetts where I was able to witness them all alone at a quiet and respectful distance this winter. After seeing one this past weekend in the blistering -5 wind-chill, I thanked my owl for the opportunity to witness it’s beauty snoozing in the sun and wished him or her a safe journey home. Happy to say no one was in earshot or view while (sniffling and blinking back tears) either from frozen hands or being the sappy snowy lover that I am. The latter I confess. As always, thank you to each and everyone of you for your time and efforts partaking in the amazing project.

Elaine, please note that in my reply to Allen I didn’t say snowy owls are in decline — we don’t, in fact, know what their population trajectory is. What we do know is that scientists had been significantly overestimating their global population for a long time, but now we have a lower, more conservative estimate based on our understanding of snowy owl nomadism during the breeding season. I suspect if you polled most snowy owl researchers they would guess that on a global level snowy owls are in decline — but that’s just a guess. We don’t have the data yet to say one way or the other. We’re actually starting work on a project that may be able to answer that question more definitively, thanks in part to all the tracking data we and our colleagues around the world have accumulated.

Thanks for the clarification Scott.

Will snowy owls return to the same area each year ?

This year we had three in the same area !! one mail two female I think

We live outside of Montréal ca . Small village,Saint Denis!!

Thx Chet

Depends on the owl, and also to an extent on its age. Our tracking data, and that of our colleagues in Canada, Greenland and Europe, seems to suggest that immature snowies, in their first couple of winters, may shift their wintering areas quite a bit. Stella, for example, was tagged as a juvenile on Amherst Island in Lake Ontario, but migrated north along the west side of Hudson Bay and has wintered in the Plains ever since. Once they reach adulthood, though, many owls become highly faithful to particular areas, as long as the prey base is there to support them. Baltimore migrated his first two winters to Maryland, but thereafter wintered on Amherst or the Ottawa River Valley just to the north — using so reliable a territory on the latter that we were able to keep tabs on him for two years after his transmitter failed, and before we were able to catch him and remove it.