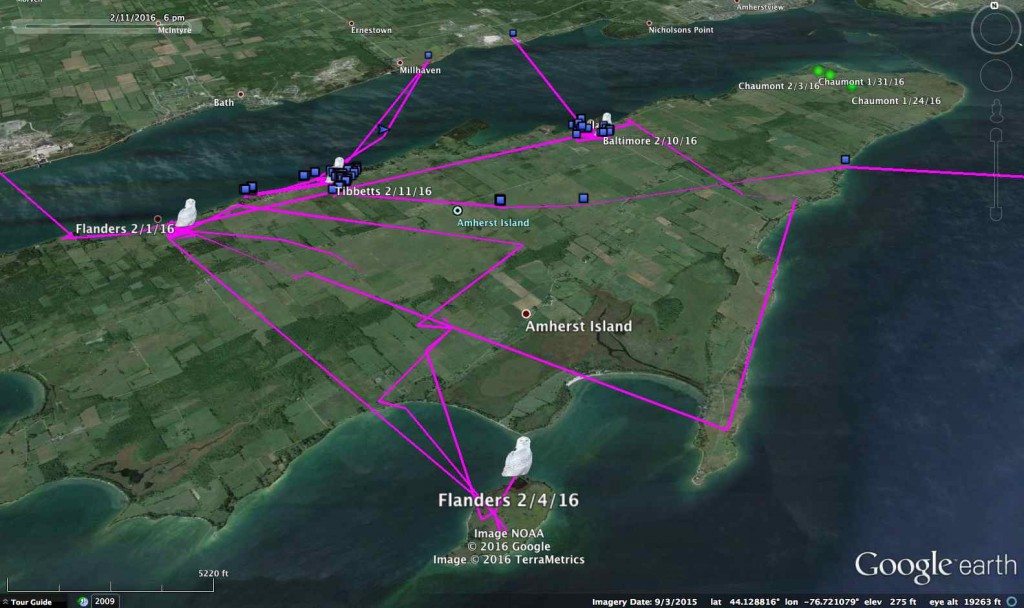

With the arrival of Tibbetts, four SNOWstorm owls are on Amherst Island in southern Ontario. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We’ve been talking all winter about how Amherst Island in Ontario has a reputation as an internationally famous owl mecca — and the fact that three of our tagged snowies have been wintering there only confirmed that distinction.

Well, make it four.

This week Tibbetts, who had been wandering around the New York side of the St. Lawrence near Chaumont Bay, suddenly put on his traveling shoes and headed north. He spent the day Feb. 7 on Grenadier Island, then at dusk skipped north along the edge of Wolfe Island and was by the wee hours of Feb. 8 perched on a barn roof in the middle of Amherst.

Since then he’s been sticking close to the north shore of the island, only about 2 km (1.25 miles) east of Flanders‘ last position, and about 3.5 km (2.2 miles) west of Baltimore.

Flanders, hanging out near the north shore of Amherst on Feb. 7, when a number of visiting birders were able to observe her. (©Katusaku)

Both Baltimore and Tibbetts made flights across the bay to the mainland — a hit-and-run visit on the part of Tibbetts, but several longer excursions across the water by Baltimore, who visited an oil tank farm and the flat expanse where a huge fiber plant was demolished a couple of years ago.

Janet Scott, the Bird Lady of Amherst, told me there have been a lot of ducks on the bay lately — that probably explains at least some of why all three owls have been spending time along the adjacent island shore. (Flanders did not check in this week, but we had a photo of her from Katsusaku, taken on Feb. 7 in the same area Flanders had been using the previous week, and other reports from visiting birders. No word from Chaumont this week, either.)

As for the others, Brunswick in Maine shifted her attention this week to the tidal marshes of Rachel Carson NWR, with none of her previous back-and-forth flights along the coast. She really seems to have settled down, perhaps because of the snow that pasted the New England coast at the beginning of the week. She has a couple of favorite rooftop day roosts, including a large motel, in the seaside town of Wells Beach.

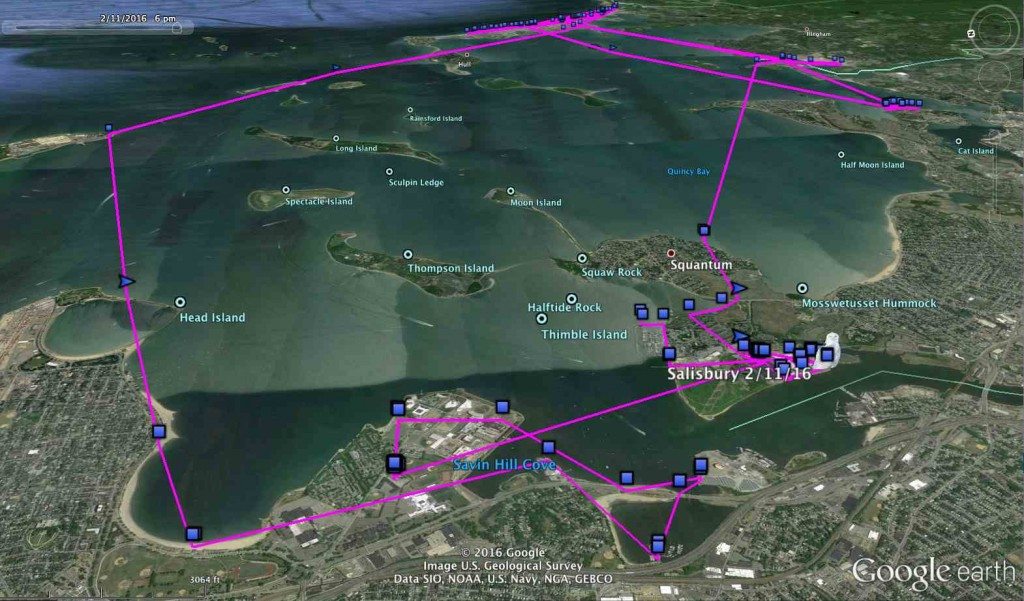

Over the course of the past week, Salisbury made a 70-mile loop around the southern half of Boston Harbor — but avoided Logan Airport. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Down the coast, on the other hand, Salisbury continues to roam all over the southern half of Boston Harbor, from Pleasure Bay in South Boston down to Quincy and South Weymouth. He spent a lot of time this past week out on Nantasket Beach, which frames the southern half of the bay, before looping back almost to Logan Airport, then winding up back at the Boston Science warehouse where he’d been roosting the previous week. (Given all the snow they got this week, the warehouse’s white roof probably isn’t the draw it had been.) In all, Salisbury moved almost 70 miles (112 km) last week, compared with Brunswick, who barely covered 20 miles (32 km).

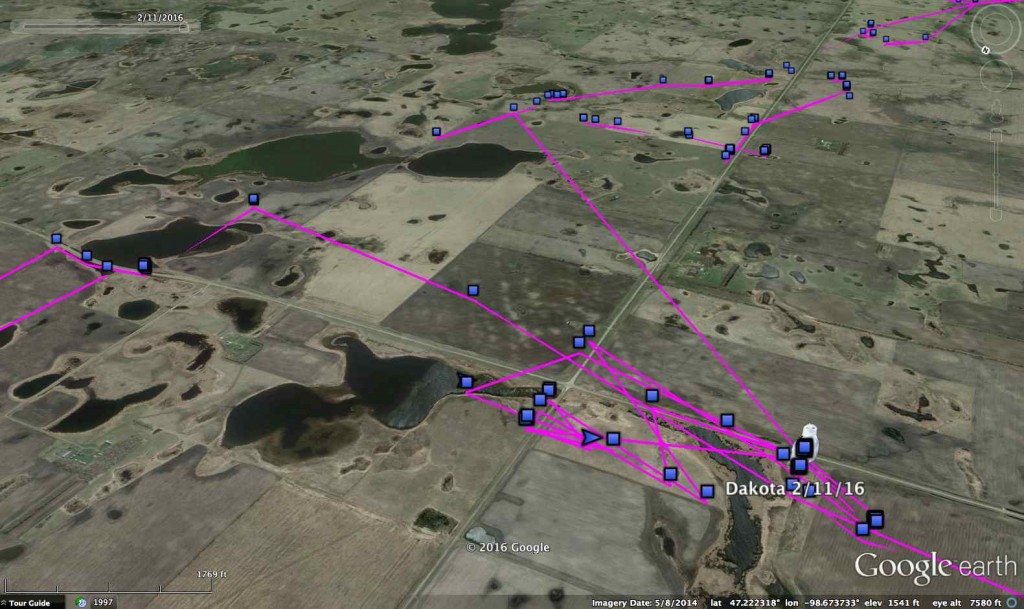

Dakota’s movements across the prairie of eastern North Dakota are showing the importance of ponds and wetlands, which in this heavily farmed region may represent the best habitat for prey. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

One of the interesting questions we can begin to answer this winter is how movements patterns for snowy owls in the Great Plains compare with birds wintering in coastal or urban environments. Dakota was moving around quite a bit this week, mostly in a narrow, north-to-south strip of prairie and grain fields about 9.5 miles (15 km) long and 3.25 miles (5.25 km) wide.

At first glance, the landscape may look flat and monotonous — but not to a bird, and certainly not to a snowy owl. Dakota’s spending a lot of her time along some of the thousands of lakes, ponds and marshes that dot this part of eastern North Dakota. In spring and summer, these wetlands constitute part of the amazing rich “duck factory” of the prairie pothole region, but they’re frozen now. So why the attention? Likely, it’s because they’re also surrounded by some of the only unplowed grassland in this grain-belt country — prime habitat for rodents, and good hunting for a hungry owl.

* * * * *

Finally, we had a terrific surprise yesterday afternoon — the first transmission this winter from Erie, one of our very first tagged owls. We’re not sure where he is — it was what we call an “I’m alive!” transmission, no data or even a current location, because his battery voltage was just above the critical threshold. We assume he just moved far enough south to start getting a decent amount of daylight, and our fingers are crossed that as his voltage climbs we’ll get his backlogged data.

Erie was our fourth tagged snowy, captured at Erie International Airport in northwestern Pennsylvania in January 2014. He spent that winter mostly on the ice on Lake Erie, migrated north to Hudson Bay for the summer, then came back south last winter to Lake Huron. We last heard from him in May, heading north across Lake Superior. We already have a tremendous body of data from his movements, and the prospect of getting another full annual cycle’s worth of data from him is very exciting.