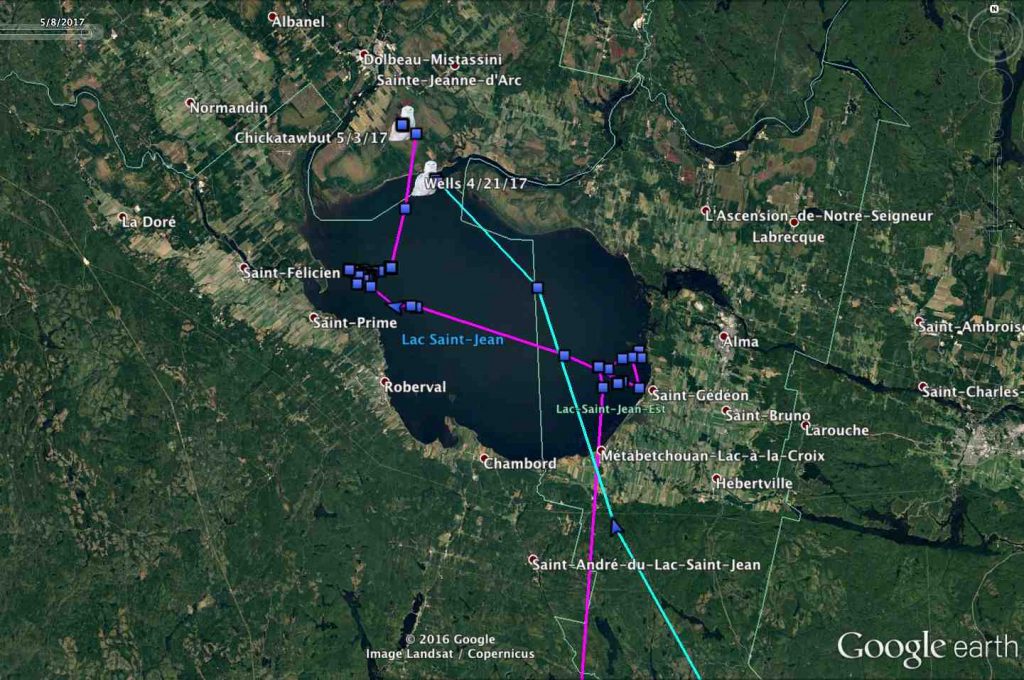

A popular place — both Wells and Chickatawbut wound up (at different times) lingering on Lac Saint-Jean in southern Quebec. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

It’s been a while since we’ve posted an update, which doesn’t mean nothing’s been happening on the snowy owl front — just that we’ve all been incredibly busy. (SNOWstorm is our passion, but it isn’t anyone’s day job, and sometimes work gets in the way.)

But the fact is that the winter season is winding down, and one by one, our tagged birds have been moving north. By this week, we have just a single owl still in cell range — a bird that was actually heading the wrong way.

First, though, let’s catch up. When last we checked in with Wells she was finally moving north through southern Quebec, having left her longtime stopover site along the St. Lawrence in Québec City. By the third week of April she was on Lac Saint-Jean, 230 km (143 miles) northwest of Québec City. That was the last we’ve heard from her, and presumably she moved out of cell range shortly thereafter.

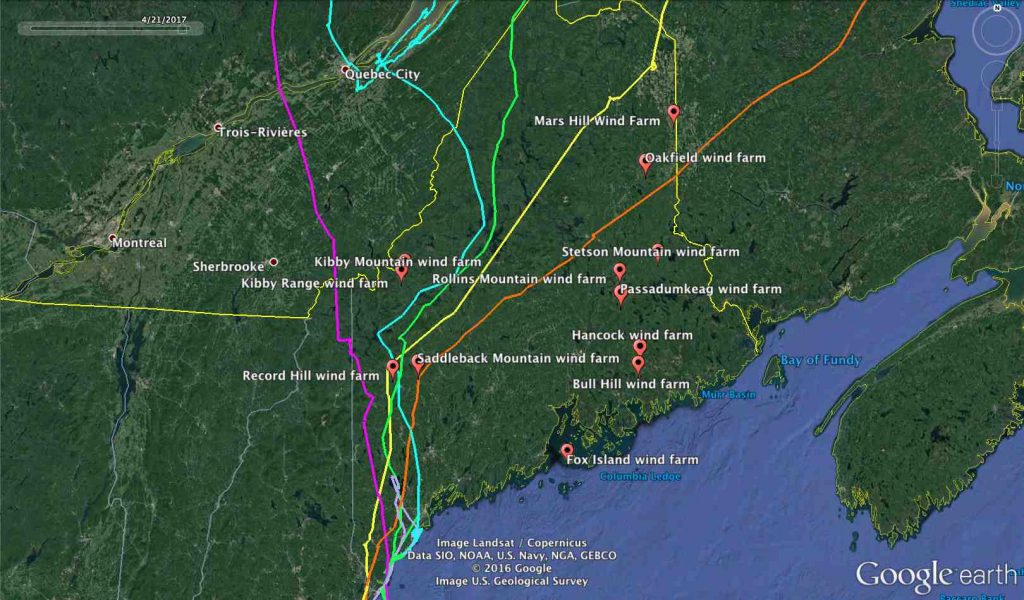

The next to move north was Chickatawbut, who had been out in the Isles of Shoals off the Maine/New Hampshire coast until she dropped off the radar in mid-April. As we suspected, she vanished because she was pushing north through the remote (and, from a cellular perspective, poorly serviced) area of western Maine. It’s a very similar track to ones taken in previous years by four other New England coastal snowies, including Wells — a surprisingly narrow alleyway up through the rugged mountains on the Maine and New Hampshire border, as you can see from this map.

Tracks from five tagged snowy owls in 2016 and ’17 show a surprisingly narrow northbound migration corridor through western Maine, an area with several large wind farms. (Chickatawbut: purple; Salisbury: yellow; Wells: blue; Brunswick: green; Casco: orange; Merrimack: silver.)(©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

That’s also an area with significant wind development, including the Record Hill wind farm (22 turbines) and Saddleback Mountain (12 turbines). Last year, judging from her altitude data, Casco flew right through the blade sweep zone of one or more turbines at Saddleback, though she appears not to have been injured in the passage, and continued to migrate north.

Last year, Salisbury flew two miles (3.3 km) west of the Record Hill turbine array, and Brunswick about four miles (6.8 km) to the east, while this year Wells passed it two miles (3.3 km) to the east the night of Feb. 19.

A closeup showing the passage of Salisbury (yellow), Wells (blue) and Brunswick (green) in relation to the Record Hill wind farm. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Maybe a miss is as good as a mile, but it’s clear from our data that western Maine constitutes an important travel corridor for snowy owls wintering on the New England coast, and as wind energy development continues in the region, we hope that regulators and developers both will bear in mind the importance of this migration route for snowy owls.

Moving out of western Maine, Chickatawbut arrived April 17 at Umbagog Lake on the Maine/New Hampshire border — one of the most pristine lakes in New England, and part of Lake Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge. After hanging out for five days, she migrated north again April 21, and for the following five days moved in stages into southern Quebec, across the St. Lawrence and, by April 26, had arrived at Lac Saint-Jean — the same frozen lake from which Wells had last checked in five days earlier.

Chickatawbut seemed to be in no hurry, and from April 26 to May 3 she was apparently riding on ice floes, which judging from the tracking data were being pushed around by prevailing winds. Finally on May 3 she flew to land, spent a couple of hours in farm fields near the lakeshore, and sent her data at dusk. She’s missed two transmissions since then, which suggests she (like Wells before her) moved north and out of cell range.

Which brings us to the last owl with which we remain in touch — Oswego, who has been a bit of an oddball all winter. This juvenile female had been hanging around eastern Lake Ontario, and as of our last update she was still out on Bass and Gull islands, and nearby Association Island, site of a big commercial campground. Given that Gull Island is a noted waterbird colony, the presence of a hungry snowy owl could pose a real issue for the nesting black-crowned night-herons and herring gulls.

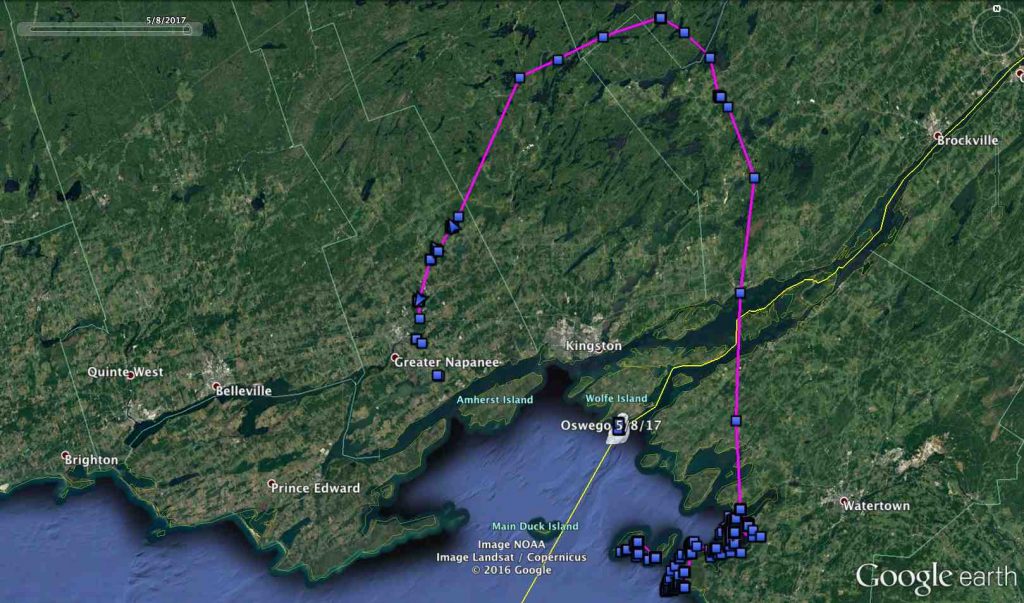

A bird in no hurry to go north: Oswego’s meandering loop through southern Ontario and back to the lake. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

However, Oswego finally started to move north on May 1, flying through southern Ontario May 2-3 — and then hooking back south again all the way back to Lake Ontario by May 7. Her transmitter, which has been erratic all winter, dropped some locations, but it appears she flew across Amherst Island and on May 8 (her last scheduled check) she was on the southwestern tip of Wolfe Island, a few hundred meters from the Canadian/U.S. border.

Why the meandering route? A lot of it may have to do with her age. Unlike all the other owls we tagged or tracked this winter, Oswego is a second-year bird, concluding her first migration. She is likely still years away from breeding age (though no one is sure exactly when snowy owls reach maturity), so unlike the adults, she’s probably not in a real hurry to get back to the Arctic.

Still, we’ve rarely had an owl stay this far south this late in the season, and some that have (like Oswegatchie in 2014) came to a bad end. We’ll keep our eye on Oswego, and hope she finds her bearings and starts heading in the right direction soon.

One Comment on “And Then There Was One”

Thanks for the update!!! Very interesting to see the data from several snowies using the corridor among the industrial wind turbines in Maine and New Hampshire, worrisome too. Lets hope the wind regulators and developers hear about this, so they can plan accordingly.

Hope by the next update Oswego has moved north instead of south! Yes, poor dear Oswegatchie stayed maybe way too long.