Baltimore as a third-year male, tagged and ready for his second release at Assateague Island in February 2015 (©Chris Hudson)

Of all the owls we’ve tagged since Project SNOWstorm started, perhaps the most exciting has been Baltimore.

He’s now wrapping up his third winter on our radar, and his second with a transmitter — and he’s produced what is arguably the most detailed record ever of the movements of an individual snowy owl.

As a juvenile on his first migration, Baltimore was initially captured in March 2014 by U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services biologists at the Martin State Airport outside Baltimore, MD. We didn’t have a transmitter small enough for him at the time, so SNOWstorm co-founder Steve Huy banded the bird and released him in western Maryland.

Last winter, though, Baltimore was back at Martin, where he was retrapped in February. This time we had an appropriate transmitter for him, so Steve and our fellow SNOWstorm director Dave Brinker, of Maryland DNR, tagged him. (The transmitter was sponsored by the Baltimore Bird Club, for which we’re grateful.)

Relocated to Assateague Island National Seashore, Baltimore was released Feb. 14, 2015 — and we’ve been tracking him ever since.

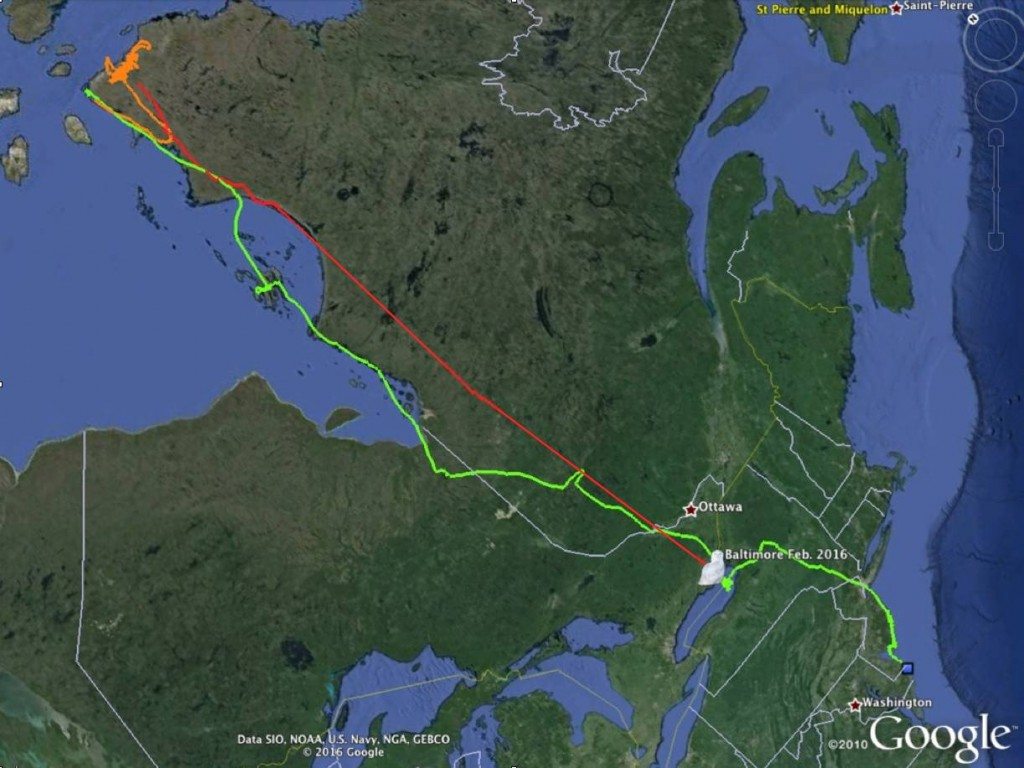

Baltimore’s route over the past year — northbound in green, summer in orange, and southbound in red (missing sections filled with straight-line patches).(©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth.)

Baltimore basks in some mild spring sunshine at Holgate NWR on on Long Beach Island last winter. (©Northside Jim)

“The information we’ve gotten from Baltimore is by far the most detailed record of the movements of any snowy owl ever tagged,” Dave said. “We have locations — accurate to a meter and in three dimensions, including altitude — every 30 minutes for almost his entire migration. That’s more than 14,000 GPS points, and counting. No snowy owl has ever been tracked for so long with such precision.”

Baltimore has certainly gotten around. After his release, he quickly moved north, and spent the remainder of that winter hunting mammals and waterfowl among the islands and tidal marshes of Little Egg Harbor and the Holgate unit of Forsythe NWR on the New Jersey coast.

On March 25, 2015, Baltimore began flying north, traveling about 35 mph and hugging the New Jersey coast. He crossed Sandy Hook and flew up the middle of Manhattan, landing for a short rest on a 58-story skyscraper (One Penn Plaza) next to Madison Square Garden. The view apparently didn’t suit him, though, because he continued quickly north, skirting the Catskills and Adirondacks to eastern Lake Ontario.

For the next two weeks, the owl spent most of his time on the decaying ice sheet that still covered the eastern third of the lake, presumably hunting the abundant waterfowl then migrating through the region — a typical behavior for snowy owls, as we’ve seen, which gravitate to ice on both the Great Lakes and in the Arctic.

April 15, 2015, the bird resumed his migration, traveling north and west through Quebec and southern Ontario. That’s when he went beyond the cellular network, and we lost touch with him — but his transmitter continued to log GPS locations every 30 minutes around the clock, storing up those data.

By May 5, Baltimore had reached the southern tip of James Bay, and a week later had crossed into Hudson Bay, which was still largely frozen. He lingered for two weeks among the bizarre Belcher Islands, which look like stretched and twisted taffy in the frigid, ice-filled bay.

Baltimore made one final, 450-mile push from the Belchers beginning May 31, 2015, and reached the tip of the Ungava Peninsula — the northernmost point in Quebec, along the Hudson Strait — three days later. In straight-line terms, it was more than 1,600 miles from where he had spent the winter. The owl detoured south again for 162 miles, then curved back north to the strait, where he spent the remainder of the summer roughly 300 miles below the Arctic Circle.

This animation shows Baltimore’s movements to and from the subarctic in northern Quebec. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

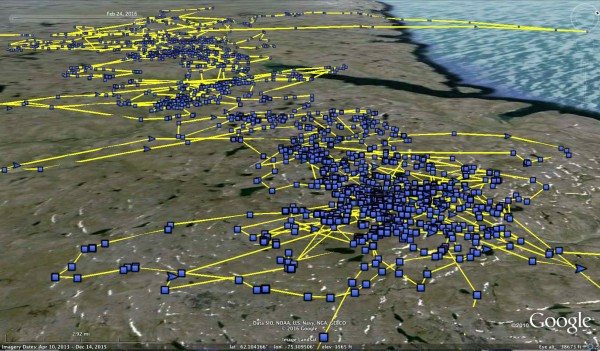

Last summer, Baltimore zigzagged more than 1,500 miles along the shores of Hudson Strait in northern Ungava — the most detailed tracking ever of a snowy owl on the summering grounds. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

As a subadult not yet old enough to breed, Baltimore had no responsibilities, so he moved restlessly and almost continuously over the next five months, covering more than 1,500 miles within an area roughly 90 miles wide by 30 miles deep. This treeless tundra landscape is home to wolves, caribou and polar bears, and is uninhabited except for the small Inuit villages of Salluit and Ikualajuuq.

Just after midnight on Oct. 31, 2015 — as the days grew short and the subarctic winter deepened — Baltimore turned south, largely retracing his northern route down the eastern edge of Hudson Bay. The short days and low sun angle sent his solar-powered transmitter into temporary hibernation on Nov. 13, but it emerged from sleep mode Nov. 29 along the James Bay Highway in western Quebec, where it also made its first transmission of stored data since the previous April.

By Dec. 19, 2015, Baltimore was ensconced on Amherst Island, along the northeast coast of Lake Ontario, which as regular readers of this blog know is where he’s spent this winter in an area of farmland covering less than a square mile. He’s been hunting ducks, eating meadow voles and delighting the hundreds of birders and photographers who come to Amherst each winter to see northern owls.

Baltimore’s time on Amherst Island this winter, including time on the ice once the channel to the mainland froze.(©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth.)

In the coming weeks, Baltimore should head north again — perhaps to breed, since he may now be old enough to start a family. The age at which snowy owls begin nesting is unknown, and our tracking data with known-age owls like Baltimore may help answer that question.

You’re help and support has made this kind of work possible. Thanks for your enthusiasm and your interest — and if you haven’t done so, please consider a tax-deductible contribution to SNOWstorm, since this all-volunteer effort is supported solely by public donations.