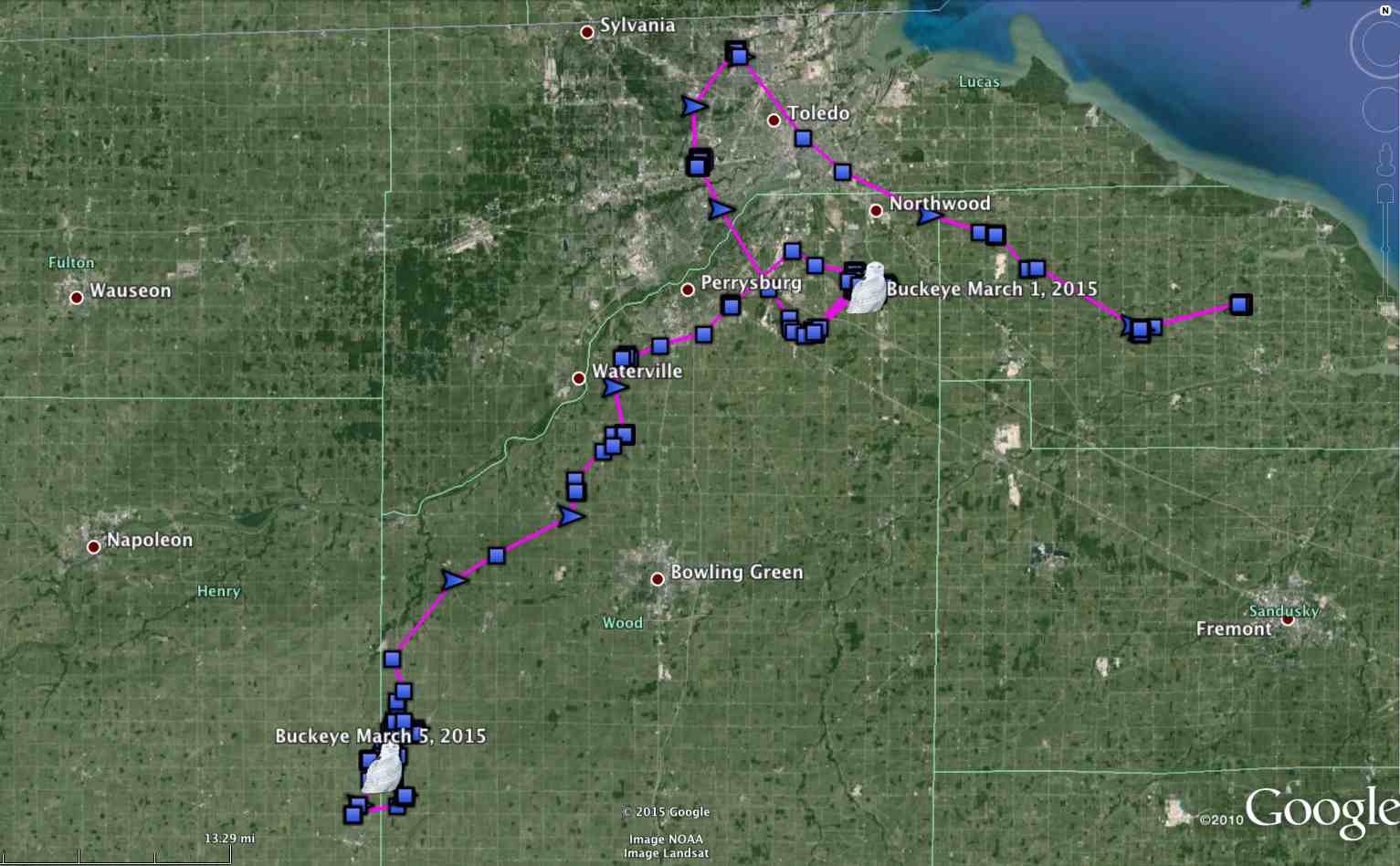

Buckeye’s movements since her release Feb. 15 — including a very welcome departure from a regional airport. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We had another busy round of check-ins Thursday night, and now that a few days have passed, we’ve updated the map for eight of our tagged owls.

The most unexpected — and welcome — change is Buckeye, who for the past couple of weeks has been haunting the runways of the Toledo Executive Airport in northwestern Ohio. Her habit of crisscrossing the runways placed her at significant risk from a plane strike, but she’s a repeat offender with airports (having been removed three times from Detroit’s) so we weren’t too optimistic she’d leave.

But she did, on the night of March 2-3, heading farther southwest about 30 miles (48 km) to the border between Wood and Henry counties. Since then she’s been hanging around the immense, flat, checkerboard farm fields of this part of Ohio. Let’s hope she likes the look of it, and stays away from airports.

Our other wandering owl has been Prairie Ronde, the adult female who moved out of southern Michigan and into extreme northwestern Ohio last week. She remains around the town of West Unity, less than two miles (3.2 km) from the Michigan border. Given the cross-state athletic rivalries between Michigan and Ohio fans, I’m sure the Michiganders would like to reclaim her.

The most resolutely Michigan owl remains Chippewa, up in the eastern Upper Peninsula. For her, a flight of half a mile (.8 km) counts as a big movement, and she’s only done that once. The rest of the time she continues to burn a hole in the map on a couple of neighboring farms near Pickford.

No major changes form Millcreek, still hanging out in suburban Toronto, or for Geneseo and Orleans in upstate New York. Chaumont checked in for the first time in a while, uploading his stored data — and like Chippewa, he is a creature of unvarying routine, remaining on the north shore of the Chaumont River and only occasionally hunting farm fields a mile (1.8 km) away. Unlike several of our 2014 owls, he’s shown no interest in heading out on the ice on Lake Ontario, which he can easily see from he favorite perches.

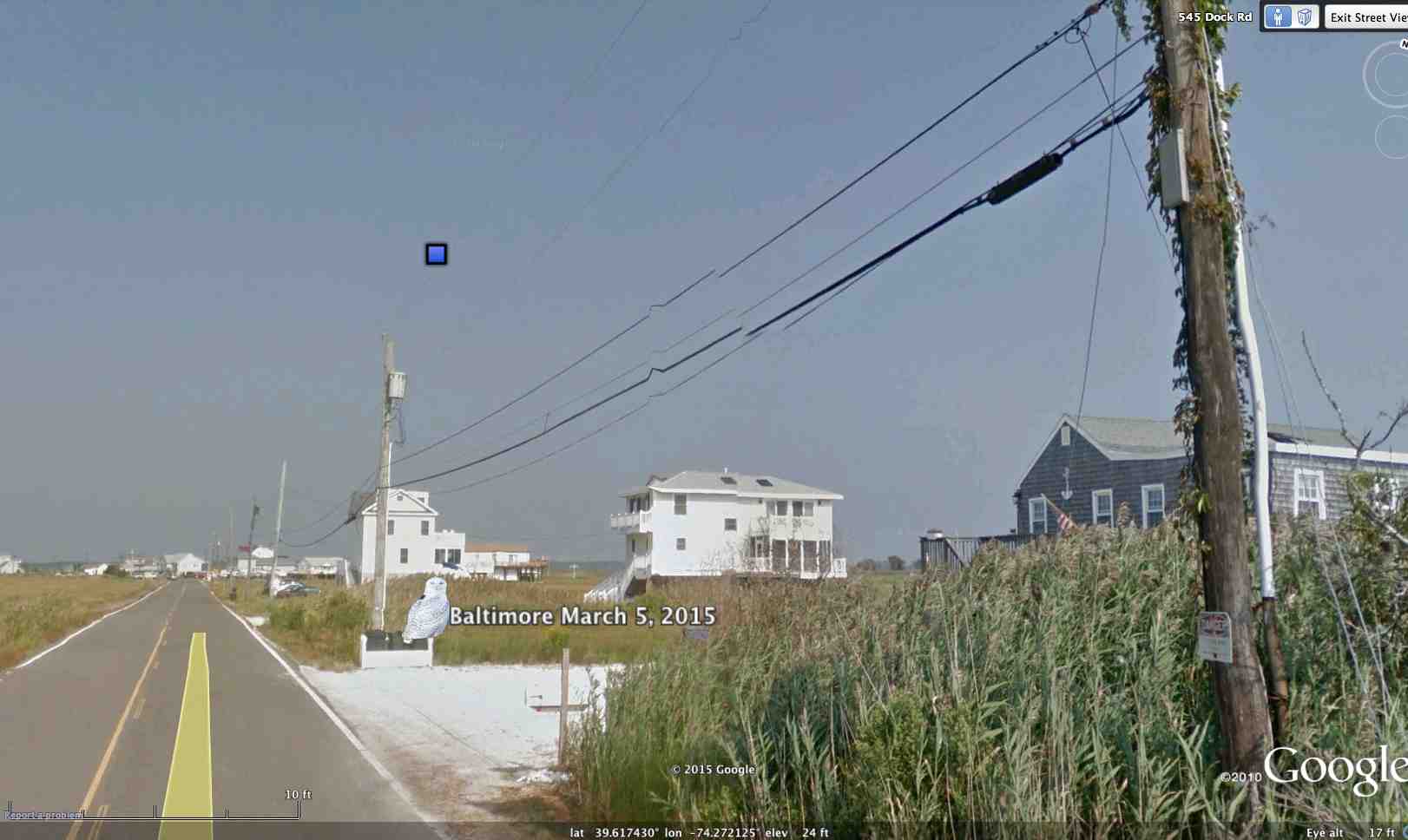

Baltimore’s latest location, on a utility pole among some (presumably deserted) beach houses by Little Egg Harbor, NJ. This Google Street View photo was taken when the landscape was a whole lot warmer and a lot less white than it is now (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The final owl whose data we got Thursday was Baltimore, who remains near Long Beach Island on the New Jersey shore. Most of his time recently has been spent on Little Egg Harbor, which is frozen. Sometimes he roosts on the many small islands in the harbor, sometimes on the ice, sometimes (as the accompanying photo shows) on the now-deserted summer homes that poke into the mainland salt marsh.

He had been using the beach and dune at Holgate, at the southern tip of LBI, but has moved on. I wonder if that had anything to do with the three other adult male snowy owls that were resident on the island all winter, and which were constantly mixing it up last month while we were trying unsuccessfully to catch them. They appeared to be very territorial, as a lot of wintering snowies are.

The big question in our minds now is when we’ll start seeing signs of northbound movement.

Last winter, most of the tagged owls began moving north from mid-March through late April — but they were all immature birds, like most of the irrupting snowies last winter. They were not old enough yet to breed, and lacked a compelling reason to rush back to the Arctic.

This year, all of our tagged owls (again, like most of the birds in this winter’s irruption) are adults. The males in particular will want to get back north quickly, find the big lemming concentrations that permit successful breeding, and stake out territories to which they can attract females.

Our SNOWstorm colleague Norman Smith in Boston, who’s used satellite transmitters to track snowy owls in years past, found that adult birds often began to move in late February and early March. It may still feel very much like winter in many parts of the Great Lakes and Northeast, but the days are lengthening and the owls are already feeling the change.

In fact, the big movements we’ve seen this week by Prairie Ronde and Buckeye may be the first stirrings of that migratory urge. We saw something similar last year with birds like Ramsey, who had been very local all winter, but then began making big flights south and west before turning north.

The next few weeks could be interesting and exciting ones, as we watch the seasons at work on our tagged owls.

2 Comments on “Buckeye Hits the Road”

Bowling Green on Buckeye’s map, is that KY?

92% of goal reached & 18 days to go! Let’s reach the goal for Project Snowstorm so they can keep tracking these wonderful owls!