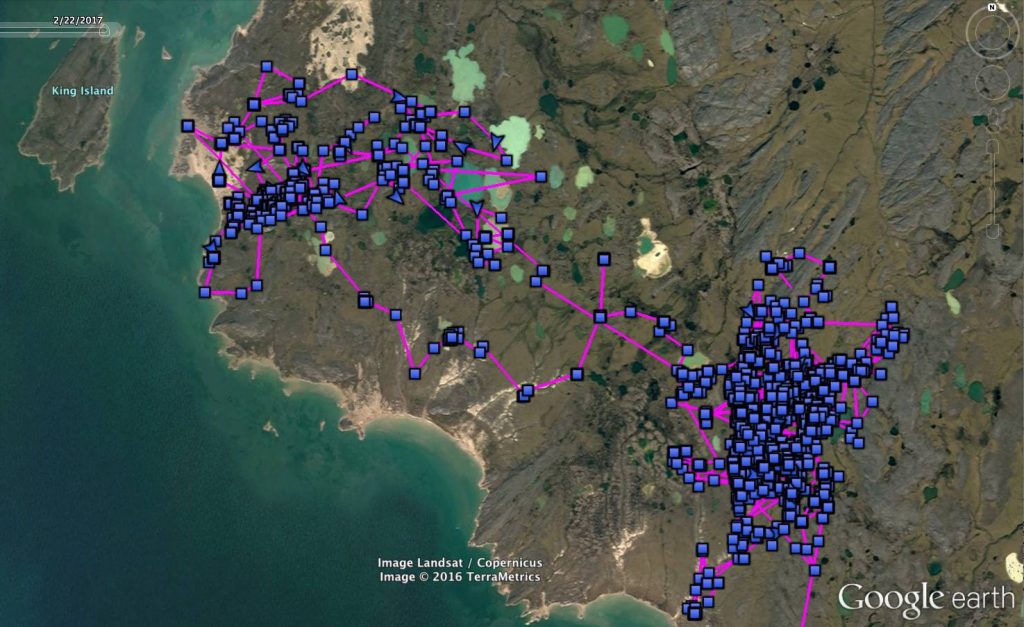

At last: Hardscrabble’s movements from late April to the middle of December — including two months apparently nesting on the coast of Hudson Bay. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

As we’ve mentioned before, due to some unexplained hiccup the transmitters on our three returnee owls — Dakota, Hardscrabble and Baltimore — all experienced a glitch on Jan. 1, when they stopped downloading their backlogged GPS locations, leaving us without seven or eight months’ worth of stored movement data.

Baltimore’s unit subsequently went completely dark (which is why we’ve tried repeatedly to recapture him), but our colleagues at CTT were able to check the other two transmitters remotely, and were confident they could recover the data from Hardscrabble and Dakota, once the owls’ solar-powered units hit a sufficient voltage level to handle an unusually long data transmission.

So for the past several weeks we’ve been watching their voltage creep up steadily toward a level that we all felt there would provide a a margin of safety beyond what CTT thought would be necessary. Finally, last night we all crossed our fingers and held our breath as CTT sent out the new firmware that would start the data dump from both birds.

It was a complete success. Over the course of 35 minutes, Dakota downloaded more than 17,000 stored data points, including all of her new (to us) GPS fixes from early July through the end of December. At the same time, Hardscrabble’s unit was downloading 10,355 new fixes that traced his movements from mid-April through the end of the year, a process that took 40 minutes.

In one fell swoop, the past year or so in the lives of these two owls was revealed.

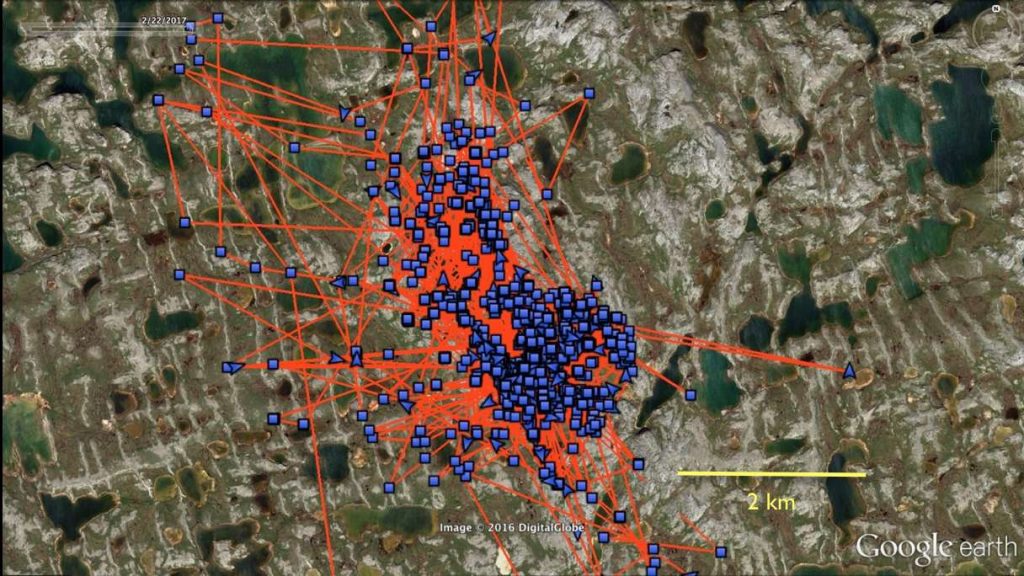

We already knew that Dakota had nested last year on the Boothia Peninsula in northern Nunavut; we’d already retrieved her data through early July, showing her barely moving as she incubated and brooded. But now we could see how her activity area expanded as (presumably) her chicks became more and more independent, and she helped her mate with hunting and protection. After remaining in an area of about 5 sq. km/2.5 sq. miles through August, she moved northwest a few kilometers and hung out for two months on Cape Barclay, along the eastern shore of Chantrey Bay.

After she finished nesting, Dakota moved a few kilometers northwest and spent the next two months in a fairly small area — quite a contrast with Hardscrabble’s long-distance movements. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Dakota started heading south in early October, wasting very little time once she departed. She flew due south for a few days, then hooked a bit west through central Nunavut, crossing into northern Saskatchewan about Oct. 26. At that point, the rapidly diminishing seasonal daylight caught up with her battery, and her transmitter went to sleep for about a week, reawakening when she reached the somewhat sunnier latitudes of southern Saskatchewan Nov. 6, four days before her unit checked in for the first time last fall.

We were even more excited to get Hardscrabble’s data, since when the glitch hit we’d only recovered a few weeks of his northbound track, through late April of last year, when he was moving north along the east side of James Bay.

Now we can say he continued north, stopping in the weirdly convoluted Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay, then cutting back to the mainland just south of the Inuit village of Inukjuak, near the Hopewell Islands.

And there he stopped on May 10. For the next two months, Hardscrabble rarely strayed beyond a small area about 1.5 square km/0.6 square miles — almost certainly a nest site, although he didn’t localize to the same extreme extent that Dakota had. (Hardscrabble’s mate would have done almost all the incubation and brooding, while he would be responsible for provisioning her and the growing family with food, and providing ferocious protection against any encroaching danger. Consequently, we’d expect him to roam a somewhat wider area than a nesting female.)

Keeping an eye on the kids: Hardscrabble remained within a very small activity area from May 10 to July 9, strongly suggesting he was caring for a mate and chicks. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Once the breeding season was over, though, Hardscrabble headed farther north, moving more than 400 km/255 miles to the northern Ungava Peninsula, then wandering widely across more than 22,000 sq. km/8,000 sq. miles of tundra — quite a contrast with Dakota’s limited post-breeding movements. He remained in northern Ungava until the very end of November, at which point the daylight had become so scant that his unit went to sleep for a week.

On Dec. 7 it reawakened as Hardscrabble moved south along James Bay, winking on and off for the following week as he migrated through southern Quebec. By Dec. 16 he’d crossed the Ottawa River into southern Ontario, where he’s remained all winter.

We started Project SNOWstorm to study the winter ecology of snowy owls, but we’d be lying if we didn’t admit that getting these incredibly precise movement records from migration and breeding season aren’t exciting — and important. It’s not just icing on the cake, because we’re now building the most detailed, year-round dataset of the movements of snowy owls ever assembled — information that is bringing new perspectives to the lives and biology of these remarkable birds.

2 Comments on “Dakota and Hardscrabble: The Rest of the Story”

Thanks for the great report!

Thanks for the update! I became interested in Hardsrabble last winter when he was reported in our local newspapers, near Ottawa, Ontario and I found out about your project. I was concerned when only a small amount of reporting was received from his transmitter, but now I am so glad that he is thriving. What a distance he has travelled! Such magnificent creatures. Thanks for all you do– and Happy New Year!