Sunset on the prairie — the perfect time to catch a North Dakota snowy owl. (©Dave Brinker)

It took a lot of long, cold hours, but Project SNOWstorm has its first tagged owl on the Great Plains — Dakota, captured this week by Dave Brinker and Matt Solensky in east-central North Dakota. She’s a landmark owl for us in several respects– the 40th we’ve tagged since we started in two winters ago.

Dave will have the full story of his road trip in the days ahead, but we wanted to share the news quickly.

Dave and Matt — a wildlife biologist and raptor bander who joined the SNOWstorm collaboration this winter — spent the better part of a week chasing snowy owls around the region of mixed-grass prairie known as the glaciated plains or drift prairie, a subtly rolling landscape of grain fields, pastures and grassland pockmarked with small ponds and wetlands, left over when the glaciers departed 12,000 years ago.

Dakota, our 40th tagged owl in three years of field work, and the first Project SNOWstorm bird on the Great Plains. (©Dave Brinker)

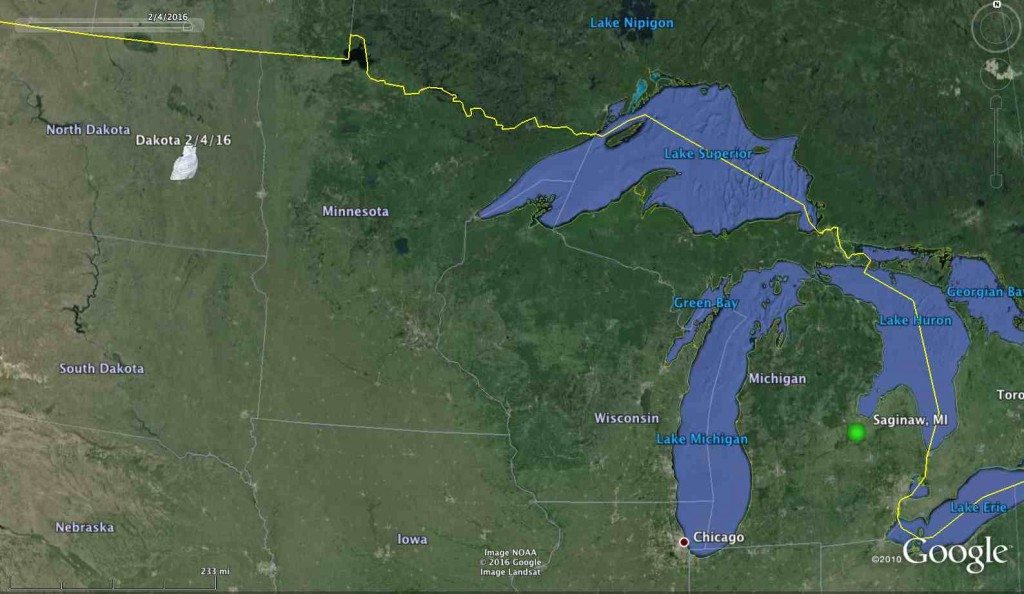

They had a couple of heart-breaker experiences before they finally caught this adult female — a bird that had been banded, interestingly, on Jan. 16, 2014, at the Saginaw, Michigan, airport. With the blessing of the federal Bird Banding Lab, as well as Aaron Bowden at Michigan Wildlife Services (the folks who had banded her originally), Dakota got a CTT transmitter and her new nickname. She was released back onto her winter territory in northern Stutsman County, southeast of the town of Courtenay and just east of Arrowwood National Wildlife Refuge.

Since then, she’s stayed in a fairly small area, about three miles (4.5 km) north to south, and 1.75 miles (2.75 km) wide. For a snowy owl, it must look reassuringly like home — flat, expansive horizons, not a lot of trees except for a few shelter belts; straight-line section roads, widely scattered ranches and an occasional deserted schoolhouse.

We’re excited to have a transmittered bird in the heart of the Great Plains, an area where we’ve wanted to work since the beginning of this project. (The closest we’ve come in the past was Ramsey, a juvenile male tagged in 2014 in southeastern Minnesota.) Comparing Dakota’s movement patterns to those of owls in eastern agricultural or coastal environments should be fascinating.

Dakota’s original banding site at Saginaw, MI, in 2014 and her capture site this winter in eastern North Dakota, some 760 miles (1,220 km) apart. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

For example, will she remain in a fairly limited area, or will the boundless horizons encourage her to move more freely than snowies in eastern inland locations, where hills, development and forests hem them in? We’ve seen some indication that snowies along Atlantic and Great Lakes coastlines may be more likely to travel greater distances, perhaps because the beaches, shorelines and lake ice don’t create inherent boundaries. Are the Plains the same?

We’re also interested in prairie-wintering owls because they represent an especially interesting facet of snowy owl migration ecology. This species has an unusual mix of migration strategies. Some individuals remain year-round on the breeding grounds, while others move irruptively and irregularly south. A few move north, to winter on Arctic sea ice.

But in the northern prairies, especially the Canadian provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan, snowy owls are regular winter migrants, and banding studies have shown that some individuals return faithfully to the same winter territory every year.

Is Dakota going to be one of them? Her current location is more than 760 miles (1,220 km) from where she was banded two years ago. She may remain nomadic, or settle into a prairie life each winter.

These are all reasons why we’re especially happy to welcome Dakota, our 40th tagged snowy owl. Check out her map for weekly updates.

Dakota’s transmitter was funded by you, the Project SNOWstorm supporters. If you’d like to help us in our work, you can make a tax-deductible contribution through our Indiegogo campaign, which is taking place right now. As always, every penny we receive goes directly into the research — and as always, we are deeply grateful for the support.