Almost pure white, Pennington is a striking presence in the small oasis of farmland amid the spruce forests of the Upper Peninsula. (©Chris Neri)

(To bring you some exciting news from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, we’re turning the microphone over to SNOWstorm collaborator Chris Neri of the Whitefish Point Bird Observatory.)

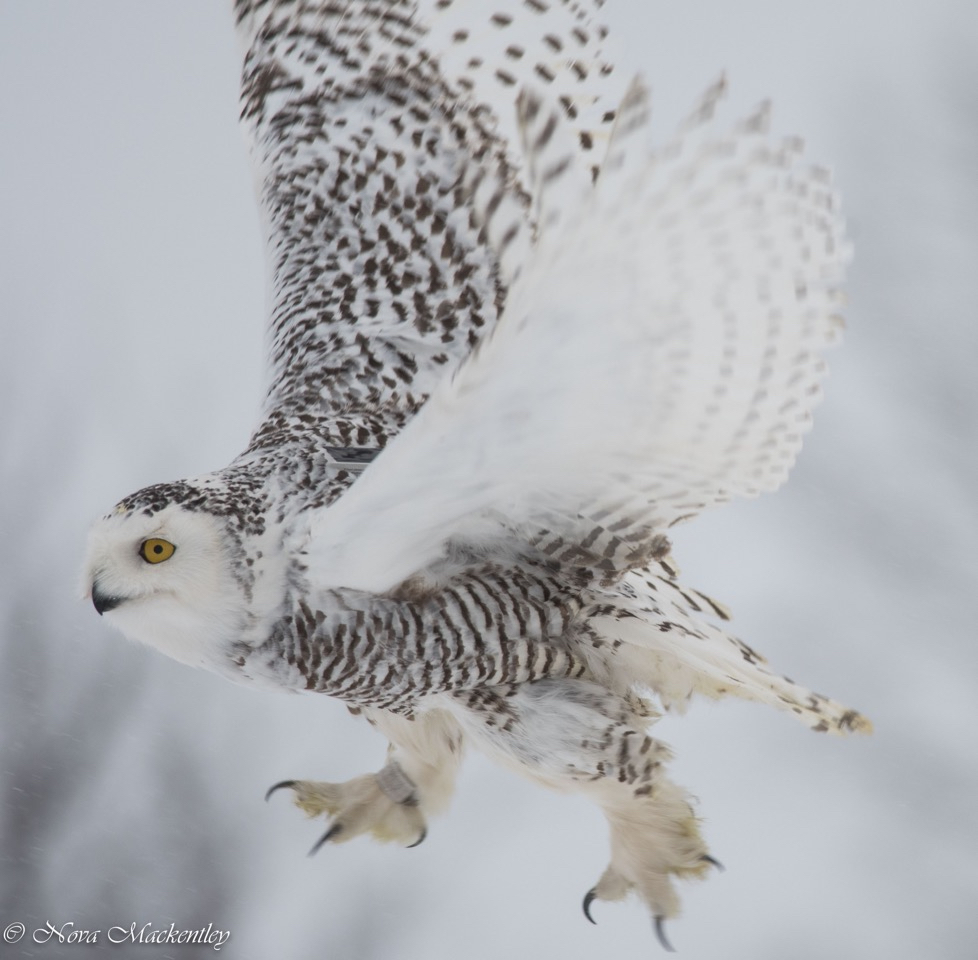

Nova Mackentley and I were thrilled to begin collaborating with Project SNOWstorm in the winter of 2015-16. Working with snowy owls is an amazing experience in and of itself, but to do so as part of this project is significantly more rewarding.

That first winter we were able to tag two adult females, Chippewa and Whitefish Point, in adjacent territories here in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, providing some unique insight into the territorial behavior of those birds. Last winter, unfortunately, was a different story; despite our best efforts, we were unable to get a single bird fitted with a transmitter. But hope returned early this winter when signs of this season’s irruption began in November throughout the western Great Lakes. In December we were able to band four snowies right in our yard along the shore of Lake Superior on Whitefish Point. For a variety of reasons we were unable to fit any of these birds with transmitters, and by January we turned our focus to tagging birds in the agricultural area in eastern Chippewa County where we had worked the last two winters. Doing our best to repress the memories of last winter’s failure, we loaded up our banding equipment and headed out. Our luck certainly changed this past weekend and we’re very excited to share two new owls with you.

Her band and transmitter in place, Pickford heads back to a territory two previous SNOWstorm owls used. (©Nova Mackentley)

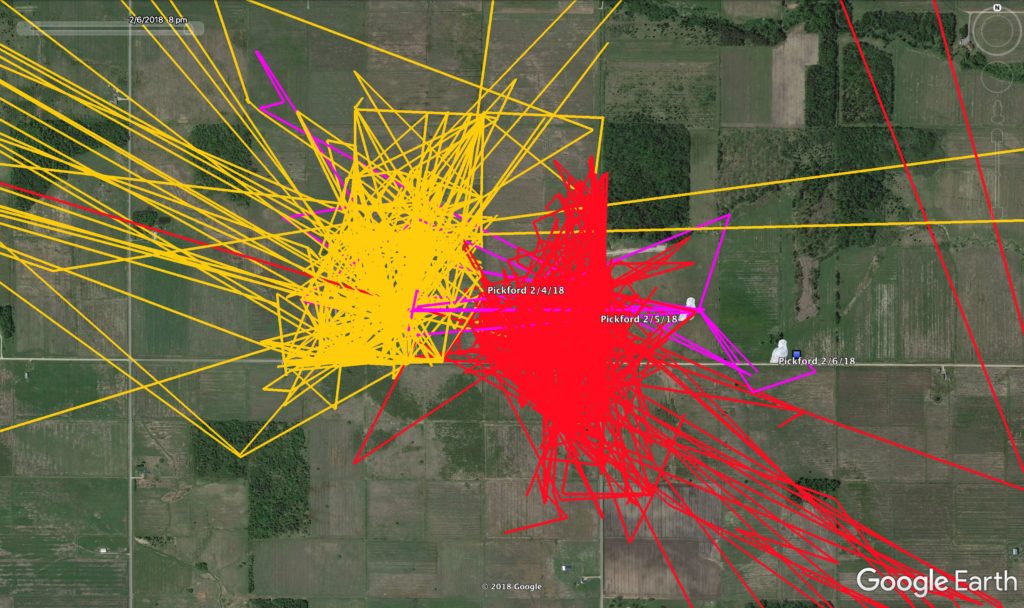

The first owl is Pickford, a very darkly marked juvenile female whose location near the town of the same name makes her especially exciting. We caught her exactly on the border of the two adjacent territories used by those adult females, Chippewa and Whitefish Point, back in the winter of 2015-16. Early data points from her transmitter indicate that she’s using parts of both of their winter territories. Pickford is a particularly aggressive bird, and we expect she will go down in our memories as the owl with the hardest bite we have ever experienced. [Editor’s note: Because Chris and Nova have banded literally thousands of owls of many species, that’s really saying something!]

Pickford’s initial tracks (purple) cover portions of the 2015 winter territiories of Chippewa (red) and Whitefish Point (yellow). (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We named the second owl Pennington, after a nearby road. Several people had contacted us recently about this completely white adult male. We’d had limited success in the past catching males, and had never caught an adult male, but you’ll never succeed if you don’t try, right? We spotted him sitting on a utility pole, but within seconds of our arrival, he dropped into the field very close to our vehicle and caught a star-nosed mole. After finishing his meal, he gave us an incredible fly-by as he returned to the same perch. There was a nearby farmhouse with a driveway that could provide an ideal location to set up our net, and the landowner graciously granted us permission. Just as we finished setting up, a snow squall blew in and hid the white owl in the white snow. We waited out the squall, and as soon as the visibility improved we saw the snowy launch from the pole, head in our direction and into the net.

Pennington gulps down a star-nosed mole, identifiable by its swollen, hairy tail — just a big gulp for an adult owl. (©Chris Neri)

We were in awe of this beautiful bird, which was almost pure white and, based on his flight feather molt, at least five years old — one of only a few fully mature males Project SNOWstorm has tracked. But we also noticed something very unusual — a small stick was protruding from his rump, the result of a long-ago accident . The wound appeared

Nova Mackentley with Pennington, trimmed and tagged and ready to go back to hunting. (©Chris Neri)

to have healed completely around the base of the twig, and there were multiple rings of dried skin around it at the base. Thankfully we had cell service (far from a given in this area) and we were able to send photos and descriptions of the situation to Dr. Cindy Driscoll and Dr. Erica Miller, two of Project SNOWstorm’s wildlife veterinarians. The wound had walled off and showed no signs of infection, and they said those rings of dried skin around the base of the stick indicated it was working its way out of the owl, which had nice muscle mass and was otherwise in excellent physical condition. (We already knew he was perfectly capable of successfully hunting.) Cindy and Erica recommended we trim the stick back to the skin, fit him with a transmitter and release him on his winter territory.

It’s obviously a very unexpected twist to this owl’s story, and we’ll be watching the data he sends back with a lot of interest. Thanks to the folks who alerted us to this bird’s presence and to the local property owners for their cooperation.

Working on this project has been extremely rewarding. Dave Brinker, Scott Weidensaul and the rest of the team have been incredibly supportive and encouraging. We cannot thank them enough for the opportunity to be part of this research project. We also thank fellow owl bander Ryan Steiner for traveling from Duluth to help us out with these two birds; we hope his thumb is healing from Pickford’s bite. This is also a rare opportunity for us to personally thank all of you who have donated to Project SNOWstorm. These transmitters were paid for from the project’s general funds and would not have been possible without your generosity.

(Chris Neri and Nova Mackentley are longtime raptor banders, and have run the Whitefish Point Bird Observatory’s owl-banding project on the U.P. in Michigan for many years.)

3 Comments on “Dark Owl, White Owl”

Thanks for the update, those are quite striking snowies, awesome photos. It will be interesting to follow on the steps, or wings I should say, of the adult male.

Dark Owl, White Owl January 2017 near Montréal Airport …..

Lovely video — thanks for posting the link.