Monday morning found me peering intently at a photograph of ‘Delaware’, our latest owl to receive a transmitter. However, I wasn’t as interested in the owl as much as what was below her perch. A blob of white with some dark matter. It looked fresh and healthy, a dropping from a bird that has eaten. But was it hers? A quick email to the photographer let me know it may have been, but the deposit was not witnessed, so we won’t ever know.

What would bring about an interest in owl poop so early in the week? This owl is special, and not just because she has a transmitter through Project SNOWstorm. Delaware has spent most of the last nine months in captivity and has only been free for a few days. She was found injured, saved through a novel surgical procedure, and rehabilitated so that she could again survive in the wild. And we are watching for signs that she is hunting, eating and behaving normally; surviving.

You may have read about Delaware in my post, “A face only a mother (and a birder and a researcher and well, just about anyone) could love” early this year. I trapped and banded her in Delaware Seashore State Park with the permission and cooperation of the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife and the Delaware Division of Parks and Recreation. We know she remained in the area of her capture for several days and then went off on her way to parts unknown. Thus completing the first of her SNOWstorm chapters.

A call from a Baltimore area airport on March 18 was the beginning of the second part of Delaware’s saga. They had an owl and wanted to know if I could come examine it. I wasn’t able to make it but my colleague, Dave Brinker, was. I soon had another call with the news that she was wearing a band and it was one of mine. It’s always exciting to have a banded bird show up somewhere and even more exciting when it’s alive and well. But then the third call came with a heavy blow, “she has a wing injury.” As the flurry of calls continued through the day and all the bits of information came together, Delaware’s prognosis for any future at all was looking really bleak. A broken bone was suspected and she may not be releasable.

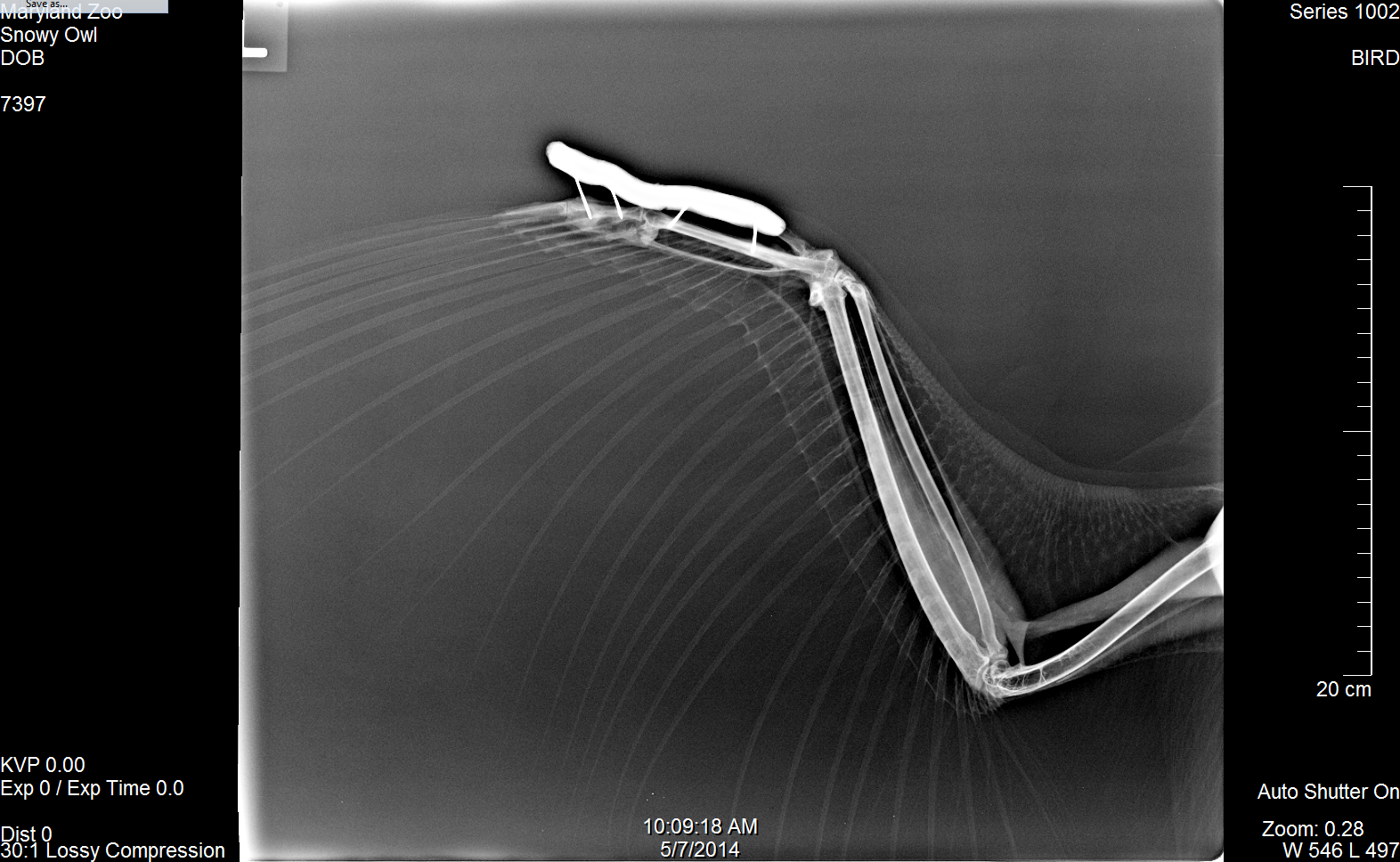

x-ray of Delaware’s wing showing pins and external fixator that held the bones in proper alignment around the damaged joint (© The Maryland Zoo)

She had been taken to the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore for x-rays and examination. Originally it was thought she had a fractured wing, but it turned out to be a dislocation of a tiny bone in the tip of her wing. The equivalent of a dislocated finger, it carries more significance in a bird that needs a fully functioning set of joints to be able to fly. A team of highly skilled wildlife veterinarians and surgeons at the zoo repaired the wing, installing several pins and an external fixator to align the bones while the joint healed.

Ellen Bronson, senior veterinarian at The Maryland Zoo, explains: “When the snowy owl, Delaware, was brought to The Maryland Zoo vet team, we were surprised to find that she did not have a wing fracture. She had dislocated one of the tiny joints at the tip of her wing – not an injury that is easy to fix effectively. So I basically did something very novel: I made the joint into a bone.

With a fracture, you put in a fixator, which is a rod that provides rigid immobilization of a fractured bone attached to pins that are placed in or through the bone. A fracture usually heals over time if you can keep the fixator in place. The tricky thing in this situation is that it was not a broken wing, it was a joint dislocation at the tip of the wing. I stabilized and basically did away with the joint and made it straight so it couldn’t move. We weren’t sure by doing this that she would have enough maneuverability in the end to make turns, but she seems to have regained function, luckily and thankfully.”

Wildlife rehabilitator Suzanne Shoemaker, of Owl Moon Raptor Center, prepares to release Delaware during flight strengthening and evaluation. Delaware is attached to a creance, a long line tethering her during training. She is gently slowed before reaching the end of the line. (© Allison Murphy)

After several weeks the pins and fixator were removed and Delaware was sent to the Owl Moon Raptor Center for strengthening and flight evaluation in early May. She was flown on a creance, a long line used to tether her while she was exercised, to build up her strength. Owl Moon director and rehabilitator, Suzanne Shoemaker also observed her flight for any problems that might prevent her release. She was determined fit and ready for release, but by this time it was the middle of our hot, humid summer. The weather was not suitable for an Arctic native and the waterfowl on which she had probably fed through the winter was gone. Attempts to ship her north for release were blocked by bureacracy or environmental issues so she was returned to the zoo until the weather improved and the proper prey would return to the area.

Delaware in flight cage at Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research (© Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research)

At the end of November, Delaware was transferred to Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research in Newark, DE so she could exercise her wings in a large flight cage prior to her release. On December 11, Delaware was finally released on Assateague, a barrier Island off Maryland’s coast. As with everything else at Project SNOWstorm, it has been a remarkable collaboration of agencies, organizations, and individuals, most volunteering their time and resources, to get Delaware back into the wild.

Dave Brinker fits Delaware with a transmitter with help from Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research Staff (© Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research)

So there I am, Monday morning, looking at poop, hoping this owl has eaten. She is wearing a transmitter so we can track her to make sure she is behaving normally. This is a sensitive time for her. She needs to adjust to being outdoors, exposed to the elements. Her food is no longer being delivered in a bowl and she must find her own. Most of all she needs to regain her strength. Nine months in captivity, even in a large flight cage, is no equal for flying to survive. She has checked in and looks like she is hunting as she treks along the coast. But this is only a guess and we will only know if she continues with normal looking movements and survives. We are going to keep her locations quiet for now, until we know she is strong again. We ask that if you see her, you do the same. Keep your distance and let her adjust and enjoy some time free of people. Once she appears to be thriving, we will release an interactive map of her travels.

You may ask, “why ‘Delaware’?” as she was found, treated and released in Maryland. She was one of the first snowy owls banded as part of Project SNOWstorm and may be the first ever banded in Delaware, where her story begins. And that has been how we have named these owls. What made her truly unique is that we suspect her of having fed on a dolphin carcass, a previously unknown behavior for the species, prior to her banding. When trapped her face was stained and she smelled awful. By her recapture in March, Dave Brinker reported, “the staining had worn off and most of the odor was gone, but she still had a faint Aroma of Yuk”. We have been referring to her as Dolphin Eater since her first encounter. The postal state code for Delaware is DE, which conveniently fits with Dolphin Eater, and it all just fell into place.

video – Dr. Allison Wack of Maryland Zoo explains Delaware’s injury and treament

video – Delaware is released – courtesy of Maryland Zoo

10 Comments on “Delaware”

Snowy’s are magnificent creatures.

Awesome!

Cristina Scarpaci

And he/she has a smile on its beak

She is a she :)

She then has a very very cute smile.

Gorgeous!

Those feet are truly amazing. Not only are they large and powerful, but they are protected by a dense bunch of bristly feathers that insulates them from snow and ice.

Beautiful bird

Thank you to all who helped Delaware. May she live a long wild free life.