The owl-fecta in hand: From left, Pat Clark of Madison Audubon (holding Fond du Lac), with Jeff Bahls of Horicon Marsh Bird Club and Brad Zinda of Linwood Springs Research Center. (©Rich Armstrong)

Wisconsin has been an important study area for us since we launched Project SNOWstorm, and it remained a priority region for us this winter, with plans to deploy two transmitters there — either on snowy owls relocated from Fox River valley airports, as we did last year, or individuals trapped on farm fields and grassland in the Badger State.

It proved to be tougher sledding than we expected, though. Our longtime collaborator Gene Jacobs was able to catch and tag Columbia at the end of January near Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary in Columbia County, assisted by Mark Martin and colleagues with Madison Audubon, which had previously sponsored the transmitter.

Gene Jacobs reading wing molt (and thus ageing the owl) on one of the three snowies caught that evening. (©Rick Vant Hoff)

But we also had a transmitter sponsored by an anonymous donor to Fond du Lac Audubon — and in February, the early luck Gene had dried up. (This is not entirely surprising, because this wasn’t an especially heavy flight year for snowies in the Great Lakes region.)

With the clock running down, though, Gene kept trying. He had made three more unsuccessful trapping attempts, and the folks at Madison airport also came up dry in multiple attempts to trap and relocate airfield owls.

All that changed the weekend of Feb. 22-23 when Gene — with help from Mark and a number of members of the Horicon Marsh Bird Club — tried a new area near Waupun, WI, where several snowy owls had been reported. A number of Madison Audubon and Horicon Marsh Bird Club members — Pat, Ben and Angel Clark, Suzanne and Jeff Bahls scouted locations on the farmland around the former Mackford Prairie on Saturday, locating seven snowies.

Fond du Lac’s left wing shows the complex of fresh, new primaries and older, more faded and worn feathers of an adult owl. (©Rich Armstrong)

Sunday afternoon, Feb. 23, Gene met the crew and split into two teams, hoping to increase their chances of getting an owl. Gene headed up one team including J. D. Arnston, Rich Armstrong and Rick Vant Hoff, with his colleague Brad Zinda from the Linwood Springs Research Station taking the other with Bahls, Mark Martin and Richard Armstrong. The split approach worked better than anyone expected. Gene’s team quickly captured two, while Brad’s caught a third — an owl-fecta, as it were. All three were taken to Rick Vant Hoff’s house for processing, with the second owl that Gene had captured, a fourth-year female weighing 2,122 grams (4.7 lbs.), receiving the transmitter.

Fond du Lac, getting ready for her transmitter. (©Rich Armstrong)

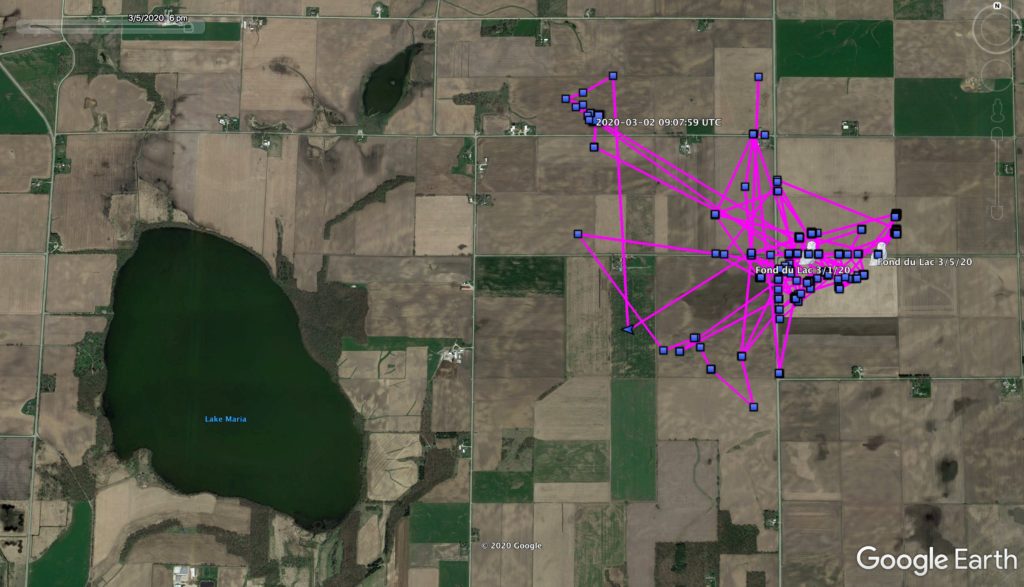

We’ve nicknamed her Fond du Lac, in honor of her transmitter’s sponsoring organization. Since she was tagged, she’s been staying close to her original capture site a bit east of Lake Maria in southern Green Lake County, using a fairly small area of about 800 acres (340 ha) of corn and alfalfa fields. But don’t take our word for it — her map is posted, so you can check out her movements for yourself.

We’re very grateful to Fond du Lac Audubon and their donor for their generosity (and their patience), and to Mark and Sue Foote-Martin and the whole crew from Madison Audubon and the Horicon Marsh Bird Club for their enthusiasm and assistance.

Since her release, Fond du Lac has been sticking tight to her capture area, east of Lake Maria in southern Green Lake County, WI. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

8 Comments on “Fond du Lac, and the Owl-fecta”

Thank you for all your dedication to informing us on the Snowy Owls. I live in Northern Ohio close to Magee Marsh and got to witness a Snowy Owl at Maumee Bay State Park.

Great to follow the ongoing accomplishments of your team, and all of the updates of the Snowies and their tracts !!

I haven’t seen alot of coverage of Owls on the east coast, (Jersey Shore), this year. Has it been an off year for this region ?? Once, again I’d just like to send out a shout out of remembrance to one of our favorites, of whom passed at Cape May, our cherished Higbee !!

You’re right, it’s been what might be considered a normal off-year for snowies in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic — relatively few owls along the New England coast, and only a few very scattered reports south of Cape Cod and Long Island. It was a fairly poor summer last year for nesting, with a few nests reported on Bylot Island and essentially none at all in other parts of the Canadian Arctic (at least those areas visited by scientists). That said, we’ve gotten reports recently of high numbers of lemmings around Pond Inlet at the northern end of Baffin Island, which suggests a lemming peak may be coming this summer. If it materializes, that *could* mean a good breeding season in the eastern Canadian Arctic for snowies, and a decent flight of juveniles into the East next winter. Lots of maybes, I realize, so keep your fingers crossed.

Is it possible to write a short tutorial on what a team looks for when capturing an owl. For example (1) what is wing molt and how do you tell age (2) everyone posing with an owl holds their legs, why? (3) any other items scientists look for which might be interesting. My questions indicate my lack of knowledge but sure would be good to understand more fully the capture process.

I am in California and we don’t have snowies here I don’t think. I am a backyard bird watcher and so appreciate the efforts of everyone who captures and tracks these wonderful birds. In fact, I will donate tonight!

Great questions, Gary. In general, we’re looking to fill out or expand our sample of particular age/sex classes or geographic regions. For example, we have a robust sample size of juvenile snowies, especially males and especially on the Northeast and mid-Atlantic coast, and to a lesser extent on the Great Lakes. We’ve been interested in tagging more adult owls, though, as well as those in prairie/grassland habitat, and relocated owls of any age (but especially adults when possible) from airports, to better understand their post-move behavior.

We can sometimes make a guess about an owl’s age in the field, but usually not until the bird is in the hand and we can look at the replacement pattern of the wing feathers — the molt to which you referred. The pattern of new and old feathers is fairly predictable through about four annual molt cycles, and has been carefully outlined by our Norwegian colleague Roar Solhein using wing photos of known-aged owls originally caught as juveniles in Eurasia and North America, then recaptured years later. It’s a slow process, and we’re still learning.

We also carefully assess the weight and physical condition of the owl. Our federal, state and provincial permits limit what we add to the owl (band, transmitter and harness together) to no more than 3% of the owl’s body weight, which is considered a conservative, safe limit. And we consider the owl’s BCI, body condition index — both muscle mass and subcutaneous fat. Only if both the weight is appropriate for the size of the transmitter (they come in different sizes) and the BCI is good or excellent will we consider tagging an owl. All of us have released (just with a leg band) many owls that we didn’t feel met our criteria for tagging.

I know this all helps greatly in your scientific research and know this research has positive effects in the long run, but isn’t this tremendously stressful for each of these owls? Both the ones you manage to catch to tag/affix transmitters AND the owls you fail to catch? Just wondering.

BTW I was lucky enough to observe a snowy several years ago (during irruption) that located in a suburban field right next to a big warehouse development in south Bolingbrook/Plainfield, IL.

Thanks for the question, Pam — our impact on the birds we study is something we keep at the forefront of our thoughts. Signs of physical stress, like overheating, are something we monitor continually, and we’ll immediately free a bird that seems like it’s having trouble. We also won’t work with a bird that, after a thorough health assessment, doesn’t appear to be in good overall condition.

Mental or emotional stress is obviously a lot harder to gauge. It’s easy to project how we would feel if the roles were reversed, and if, say, we were abducted by aliens. But we need to remember that birds are not little people, and their reactions and perceptions aren’t the same as ours. For instance, for almost 20 years I’ve been one of the few banders licensed to work with hummingbirds, and given the size disparity you’d reasonably expect that they’d be especially prone to mental stress when captured. Yet virtually every hummingbird I’ve ever banded would without fail, greedily drink from a feeder as much as I’d let it while being held. I can tell you, if an alien did what aliens are supposed to do to me, then offered me a cheeseburger, I would not eat it. And it’s not just hummers — I’ve had warblers snatch deer flies out of the air while I was holding them, then gobble the bugs once I released them.

Snowy owls are famously chill around people, and with a few exceptions that’s been my experience with them in the hand as well. I can’t know for sure what’s going on in their heads, but the speed with which they return to their normal activity after we release them makes me reasonably sure we’re not traumatizing them.

I wish I had the money to have had 2 more transmitters there that day. However at 80 years plus and just basic government t pension am unable but very thankful to all that can and do,

George,

Sask. CA.