Island Beach, the first of two New Jersey snowy owls tagged last week at this bird’s namesake state park, heads back to the wild with a transmitter. (©Mike Lanzone)

From literally the beginning of Project SNOWstorm in 2013, we’ve tracked snowy owls to the New Jersey coast. Our very first bird, Assateague, was captured in Maryland but quickly flew to New Jersey and spent the rest of the winter there. So, in subsequent years, did others tagged farther south, like Hungerford and Baltimore. But despite many attempts we’ve always come up snake-eyes trying to catch and tag an owl in the Garden State itself.

Mike Lanzone from CTT checks Island Beach one last time before releasing the owl. (©Karmela Moneta)

Until now. In one fell swoop, two of SNOWstorm’s core members — Mike Lanzone from Cellular Tracking Technologies (who makes the transmitters we use), and David LaPuma from New Jersey Audubon’s Cape May Bird Observatory — last Wednesday caught and tagged two young male snowies at Island Beach State Park, “down the shore,” as folks in that part of the world like to say. (This is the second double-header for Mike; in 2014 he and Tom McDonald tagged two owls, Erie and Millcreek, the same night in Pennsylvania.)

Because we knew up to five snowies had been present at IBSP, this was a perfect opportunity to look at interactions between neighboring owls, one of our long-term research goals. Despite the high numbers of birds reported just a day earlier, on Wednesday morning when Mike and David arrived the owls were few and far between. After an hour and a half of searching several miles up and down the beach (something allowed at IBSP with a state off-road permit) Mike and David spotted a bright white owl perched atop a fencepost along a beach access road. This snowy was quite active, and appeared to have hunted successfully the night before, as evidenced by the smudge of blood on its face and around its legs and feet. After much waiting, “Island Beach“ was captured — a juvenile male weighing a respectable 1,680 grams. He was tagged and released just after sunrise, much to the enjoyment of a cadre of photographers that had gathered around the banding team leading up to and during the tagging process.

(For a slow-mo video of Island Beach’s release, go here.)

“With our first snowy tagged, we set out to hopefully find a second,” David reported. “Working with park personnel, we scoured all of the sites where snowies had been seen over the previous week, to no avail. Bald eagles, northern harriers and Cooper’s hawks were moving over the dunes, as scores of red-throated loons headed south offshore. It was a beautiful day to be at Island Beach…but the one thing lacking from the landscape was the one thing we were looking for.”

Hanging out in the dunes — and very definitely not interested in the team’s lure — the second owl was a portrait in ambivalence…until dusk came. (©Mike Lanzone)

“After making our way south as far as the Barnegat Inlet, we decided to take another pass north along the beach, retracing our steps, and hoping for a different result. We made it as far as the driving beach boundaries and parked at the ‘No Vehicles Beyond This Point’ sign. Some of us scanned the dunes, while park staff and Mike scanned the beach.”

” ‘I’ve got an owl,’ Mike said to park manager Charlie Welch, and we quickly reassembled to see whether this bird was different from the one we tagged earlier. With a park escort, we drove into the restricted area and determined that indeed this bird was new.” Although the team was elated, they still had to capture it, and then determine whether it was large enough to be fitted with a transmitter.

“This bird proved much more difficult to trap, showing no interest in our lure and preferring to roost right there on the beach instead,” David said. “A runner approached from the opposite end of the beach, and while we tried to wave him off, he was oblivious to what was going on around him until the owl lifted off in front of him disappeared into the dunes. Well, there went our chance! Knowing the snowy was safe from human activity in the dunes, we decided to take a lunch break and return later in the evening, when we hoped the bird would be more active.”

Arthur Nelson of the Cape May Raptor Banding Project lends a hand as Lanzone fits Lenape’s transmitter. (David LaPuma)

That hunch paid off. Back at the park late in the day, and only 30 minutes after setting up, the team captured the second owl, and quickly had it banded — and weighed, a crucial step. For the owl’s welfare, the transmitter, harness and band together can’t weigh more than 3 percent of the bird’s weight, and we tend to be even more conservative than that. In the case of Island Beach, the first owl of the day, the total was less than 2.5 percent. This second owl, also a juvenile male, was even heavier — a plump 1,850 grams, meaning its unit comprised just 2.1 percent of its mass.

Island Beach Park manager Charlie Welch, Mike Lanzone and State Park Police officer Mike Madden pose with Lenape before releasing the newly tagged owl. (©David LaPuma)

As the sun set and the sky darkened, the team banded, measured and fitted the second owl with a new high-resolution CTT transmitter. The team nicknamed this bird “Lenape,” after the Natives who inhabited Island Beach State Park long before European settlers — but likely not before snowy owls. With only a sliver of horizon still aglow, park manager Charlie Welch released the bird back into the wild, watching it fly off to find an evening meal among the dunes and marsh.

Lenape flies off into the sunset, its movement no longer a mystery. (©Mike Lanzone)

Tagging two young males is a nice compliment to the two juvenile females Tom McDonald tagged last week in upstate New York. Charlie Welch wasn’t surprised that both new birds were hefty. “We’ve got a big rabbit population here in the dunes, and the back bay is full of waterfowl, bufflehead and red-breasted mergansers especially,” he said. We know from our Project SNOWstorm data that these coastal owls often feed both on land and over water, so we look forward to what data these two birds can tell us about their preferences. Additionally, tagging two birds in close proximity gives us the opportunity to study their interactions. Do they partition the land and resources around them? If so, how? We had a glimpse of this in 2015, when we tagged Chippewa and Whitefish Point on adjacent territories on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, only to find they never trespassed on each other. Will Island Beach and Lenape act the same way?

Island Beach State Park is also a very popular destination for outdoor enthusiasts, pursuing everything from birding to surfing, sunbathing, hunting and fishing. Hosting part of the snowy owl invasion of 2017 has provided park staff with a unique opportunity to reach many different groups and educate them about the importance of this coastal habitat for sustaining these birds through the winter, as well as providing unique opportunities to safely view these birds without negatively impacting them. “Even during the tagging process our team was flanked by visiting photographers here to see the owls, and we had an enjoyable time sharing the process with those who were there, most of whom were already very familiar with Project SNOWstorm,” David said.

Lenape’s transmitter was paid for with donations from the public to SNOWstorm’s annual fundraising campaign. Island Beach’s, on the other hand, is being underwritten by New Jersey Audubon, one of Project SNOWstorm partners, whose twofold mission is to connect people to nature, and steward the nature of today for the people of tomorrow. “We have been hoping to sponsor a New Jersey owl for three years, so you can imagine how excited we are to have a transmitter put on a Jersey bird today. Even more, we’re thrilled that it is happening in one of our state parks whose mission includes both strong stewardship, and making the connection between our residents and visitors and the natural world. Everyone at the whole organization is excited to see what these birds do, and where they go this winter,” David said.

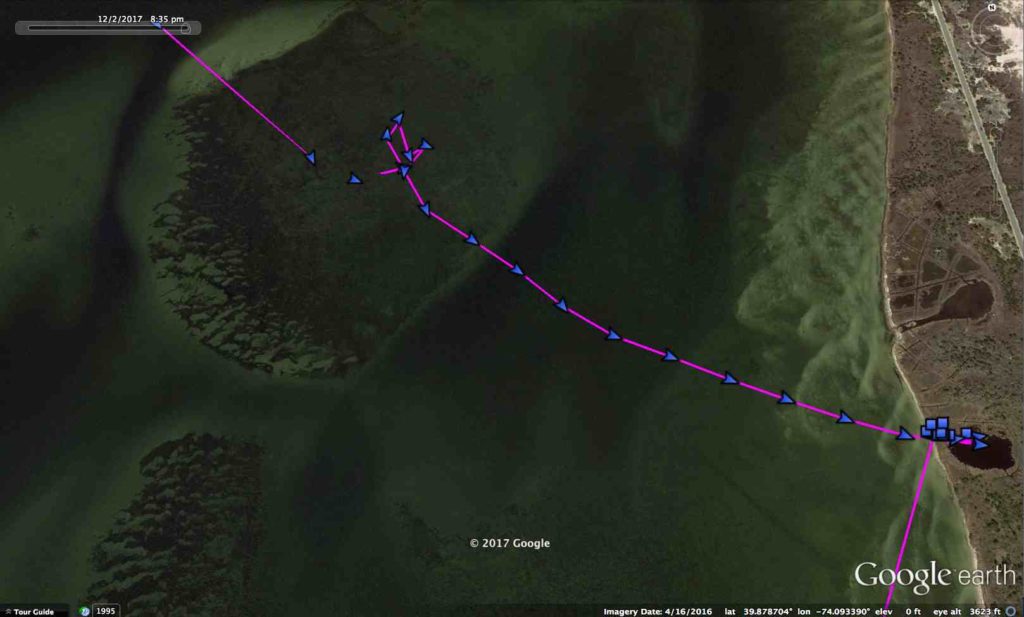

A series of quick, nighttime turns in the middle of Barnegat Bay suggest Island Beach made an attack, then flew to land — perhaps with a waterfowl snack. The new “flight mode” setting on CTT transmitters records flight data every six seconds while the bird is in motion. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We’re also trying an experiment with Island Beach and Lenape. CTT has made some big strides in its transmitters, including the addition of an inertial measurement unit, which allows the transmitter to sense and record attitude, angular rates, linear velocity and position. We’ve programmed these two units to take data every 30 minutes most of the week, but on weekends they will work in “flight mode” — whenever the owl flies, they will collect data every six seconds, giving us an incredibly detailed record of their every twist and turn.

We’ll be keeping a close eye on their storage batteries, making sure the units’ solar recharge can keep up; if so, we may expand the flight mode to additional days (and other transmitters). And it should be a highly revealing window into owl behavior — for example, we’ve already seen what looks like Island Beach making a series of quick turns over Barnegat Bay, likely in pursuit of dinner. Stay tuned for more.

6 Comments on “Island Beach and Lenape, Down the Shore”

Flight mode sounds incredible! Can’t wait to see what new and interesting behaviors we can glean from the high resolution location data.

Congratulations, Mike and David! Looks like Project Snowstorm is in for a busy season!

Are the owls still at Island Beach?

There are still snowies being seen at Island Beach, but only one of them has a transmitter. We’ll have a weekly update on all the tagged owls over in a day or so, but suffice to say that one of the two IBSP birds has some wanderlust.

Lenape has been sitting on the grass in front of our house for a few hours in Parksley Va. sea side.

John,

Tell the wandering Mr. Lenape we send our regards — he’s been the most ambling owl we’ve ever tagged, and he’s sure put a lot of miles under his wings this winter.