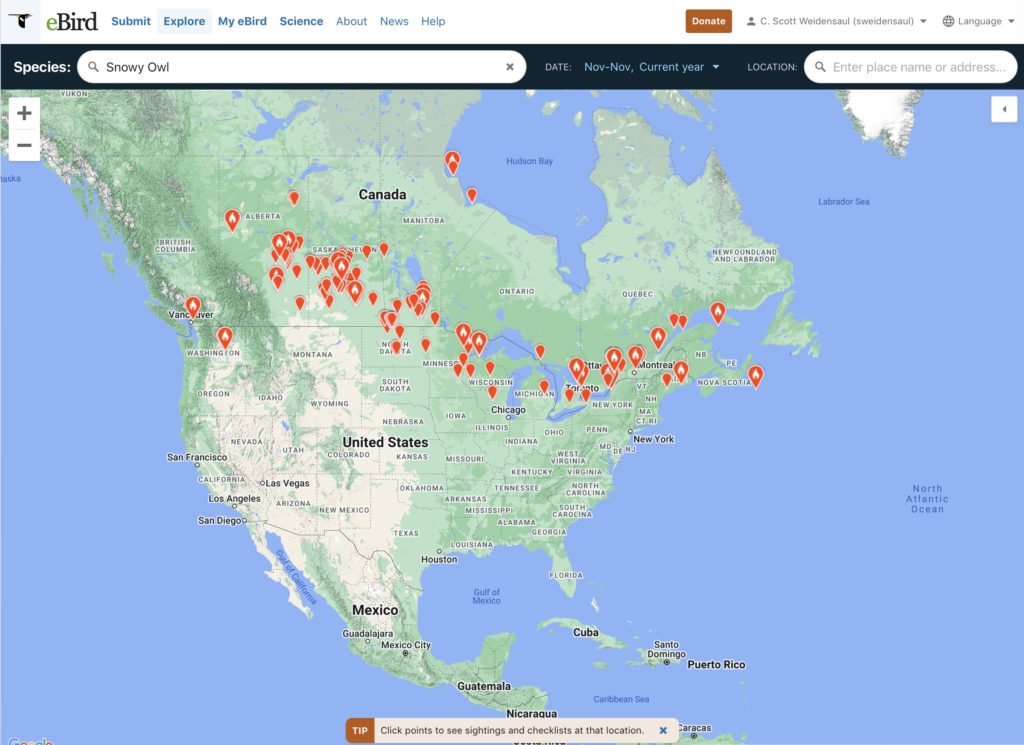

November eBird records for snowy owls in North America. (©Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

This is the time of the year when I spend a lot of time on eBird, watching for new reports of snowy owls popping up across southern Canada and the northern United States. And within the past two weeks a lot of owls have been reported in a wide band from the Canadian Prairies through the Dakotas, Great Lakes, Ottawa River/St. Lawrence valley and parts of northern New England — even one on Sable Island, 200 km (125 miles) off the Nova Scotia coast. A couple have also been reported in the Pacific Northwest, one near Vancouver and the other in central Washington.

Columbia seems to be content, at least for the moment, with the farm fields north of Riding Mountain National Park.(©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

So far, Columbia is the only tagged owl to come back in cell range, though it’s still early; most years our alumni show up from late November through New Years. She remains very close to where she initially checked in two weeks ago, in southwestern Manitoba just north of Riding Mountain National Park. It sure looks as though Columbia came south, took a look at all that boreal forest just ahead in the 2,969 sq. km. (1,150 sq mile) park, and decided to just hang out on all the nice flat, open agricultural land southwest of the town of Dauphin.

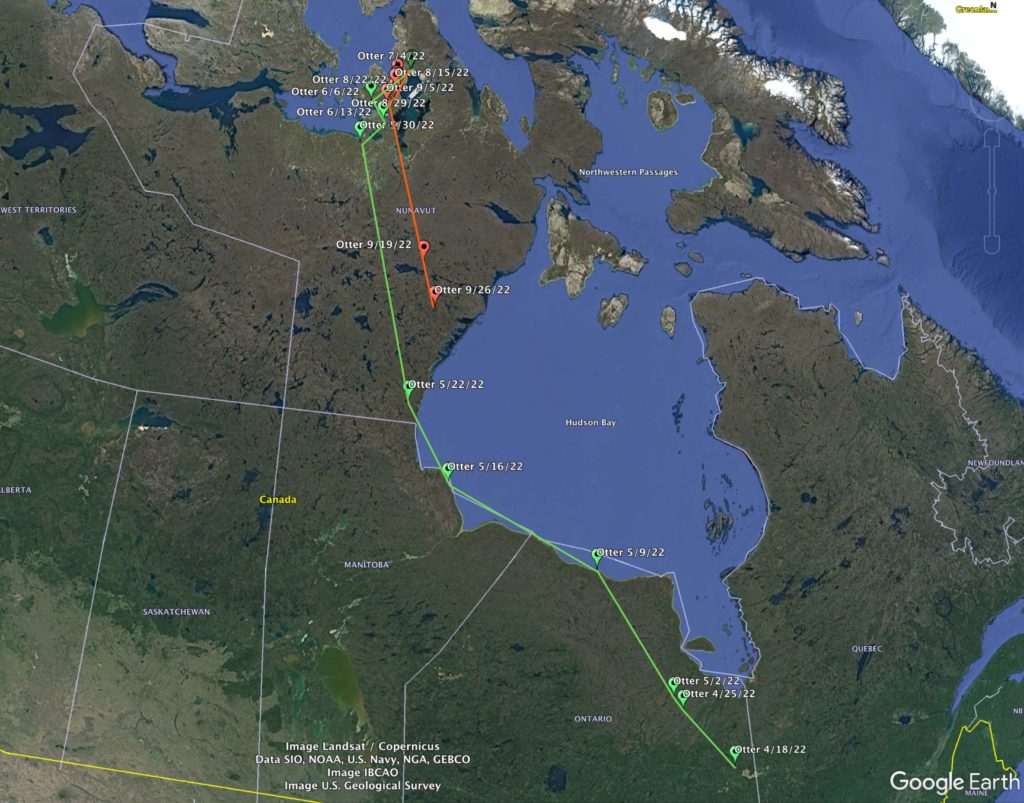

Otter’s northbound track (green) and the beginnings of his southward movement (orange), based on weekly Argos data April-September 2022. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Most of our owls are out of touch all summer when in the north, but we have one exception: Otter, who was fitted with a hybrid transmitter that sends data both by our traditional GSM service when in cell range, but also checks in once a week via the Argos satellite system from March 1 through Sept. 30 while in the north.

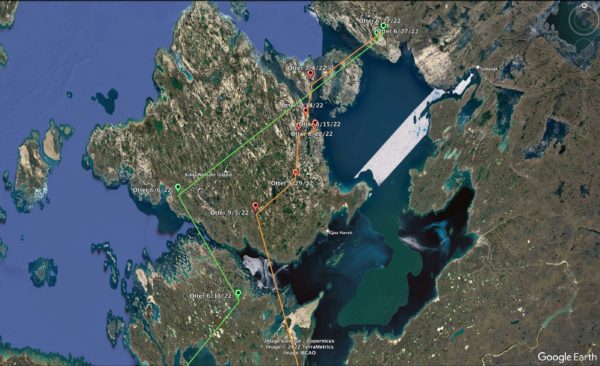

A close-up look at Otter’s movements over summer 2022. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We tracked Otter’s movements over the past spring, summer and early fall. Northbound, he skirted the southern edge of Hudson Bay in May, then migrated up to King William Island and the neighboring Boothia Peninsula. This is the first time he’s been that far west in the central Canadian Arctic; in previous years he summered near or south of Baffin Island and the Foxe Basin. (Unfortunately, these Argos points won’t show up on Otter’s map on our site, which uses the GSM-based data.)

It’s hard to be sure from the coarse Argos data, but it seems unlikely that Otter had a nest this past summer, given how much he was moving around. We’ll get a much more detailed look at his movements if he comes south into cell range, because then the GSM side of his transmitter will kick in and send us all his backlogged GPS data since last April. But there’s no guarantee he’ll come that far south. In the winter of 2020-21 Otter remained in the subarctic in northern Québec and Labrador, and perhaps he’ll do so again this year.

* * * * *

Speaking of eBird, the wizards at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology recently unveiled new status and trend maps for hundreds of species of primarily North American birds, covering the period from 2007-2020 and showing the cumulative change in relative abundance at a remarkably fine scale — each circle on the map represents a 27 km x 27 km area.

While some of the trend maps showed surprisingly good news for species of longtime concern, like wood thrushes (which, while in serious decline in the Northeast, show widespread increases in much of the rest of their breeding range), the news is not good for snowy owls.

The winter range trend map for snowies, which you can view here, shows significant declines in several parts of what I think of as the species’ core winter range in North America, especially the Ottawa/St. Lawrence river valleys in Ontario and Québec, and the southern Canadian prairies in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Elsewhere, the map shows stability (white circles) or mild declines (small red circles) in much of the rest of their wintering range. Given the general and understandable lack of birding coverage in the Arctic, eBird does not have a trend map for the snowy’s breeding range.

This new eBird analysis is one more dataset that will factor into the global status assessment for snowy owls that SNOWstorm team member Dr. Rebecca McCabe is producing, and which is partially funded by SNOWstorm contributions.

* * * * *

Snowy owl in flight. (©Jean Hall)

As most of you know, tomorrow is Giving Tuesday, but many Project SNOWstorm supporters started making generous donations to our work as soon as this season’s campaign went live two weeks, for which we are very grateful. The fact that so many of these gifts have come from folks who are by now familiar names to us, and who have been supporting this work for years, is especially gratifying. Thank you.

Because our home institution, the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art in central Pennsylvania, is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, all U.S. contributions are tax deductible. You can contribute online to the GoFundMe campaign here, or you may also contribute directly by mailing a check to the center at 176 Water Company Rd., Millersburg PA 17061. (Please indicate on the check that the donation is meant for Project SNOWstorm.)

If you haven’t seen the full update on our plans for this season and the rest of 2023, you can catch up here. As you’ll see, we have a lot on our plates.

We also recognize that this is a challenging year for a lot of our friends, with inflation high and heating and fuel costs particularly painful. If you have given in the past and can’t do so this year, we understand. You can still help by sharing word about our project, and your enthusiasm for snowy owl research and conservation, with those who might not know about Project SNOWstorm. But mostly, just be sure to stick around and be part of the community we’ve built over the past decade.

8 Comments on “Moving South”

Thank you so much, ALL, for what you do! I put “everything aside” when I see an “update” and try to envision where each of these precious God’s Creatures are! Thank you.

Was a snowy owl observed at Sunset Beach, NC?! Someone posted a pic but it seems so unlikely…?

Just wrote re: snowy in NC…never mind! Just found out more info and it was not a recent pic. Sorry!

No problem – when I saw Sunset Beach, NC, I wondered if it was the owl from a couple of years ago down there.

We usually enjoy a healthy population wintering here at our local marsh (Oconto, WI), but haven’t seen any of our beloved snowies yet this season. Is it too early to panic?

I wouldn’t panic by any means. We know snowy owl winter populations are, if not exactly cyclical, at least widely varying from year to year. As we mentioned in a previous post, from what reports we have this past summer was not a big breeding season in the parts of the eastern and central Canadian Arctic from which most of the snowies that show up in the western Great Lakes and Northeast originate. So we’re expecting a low year, which is normal after the decent irruption we enjoyed in that area last winter. You also need to factor local prey populations into the equation; if voles and other rodents are low in a particular wintering region the owls may show up, look around and push on for greener pastures. That’s why one area may have a multitude of raptors one year and few the next.

Thank you for your reply, Scott; I greatly appreciate it! We have indeed noticed what seems to be so far a lower number in muskrats than last year. I am still hopeful we will have some visitors There have been two sightings in Green Bay about 45 minutes south as the snowy owl flies.

Hi friends! Hoping to see some of our beloved snowys in NJ, but it seems to be too early. I know last year was a larger influx, but I am hoping we get some visitors this year.