Since they were tagged the third week of November along the south shore of Lake Ontario, Hilton and Sterling have moved hundreds of miles to the west — in Sterling’s case, almost to Lake Huron. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

It’s been a while since we’ve done a roundup of what all our tagged owls are up to, and some of the movements have been fascinating.

The most dramatic by far have been by Hilton and Sterling, tagged by Tom McDonald on the south shore of Lake Ontario. Like many owls along the eastern Great Lakes, they’ve moved far to the west since they were tagged, and both are now in southern Ontario.

Hilton dropped down the north shore of Lake Erie, and since the beginning of December has been near Port Dover, Ontario, and just east of there at the site of the former Nanticoke Generation Station, which before its decommissioning in 2013 (as part of Canada’s efforts to fight greenhouse gas emissions) was the largest coal-fired power plant in North America. Hilton’s been perching on the old jetties and coaling docks that jut out from the station into Lake Erie, and some of the station’s buildings.

Island Beach likes his namesake park, roosting on the beach and hunting Barnegat Bay — including using a channel marker as a perch. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Sterling’s gone even farther afield, hugging the south shore of Lake Ontario, and then moving another 115 km (72 miles) northwest, into Perth and Huron counties, Ontario, near the town of Listowel. This is a region of gently undulating farm fields and woodlots only 50 km (30 miles) from the eastern shore of Lake Huron, but since Dec. 5 she’s seemed content to stay in the agricultural area rather than the lakeshore. Perhaps she’s found a good prey base of voles or other small mammals, but it’s the longest Sterling has stayed in one area since she was tagged Nov. 26 almost 360 km (220 miles) to the east.

Turning south and east, Island Beach — one of the two young males tagged at his namesake state park along the middle of the New Jersey coast — has stayed pretty much in the same area where he was caught, using about a three-mile (5 km) stretch of beach during the day to roost, but then hunting the back dunes, tidal marsh and open water of Barnegat Bay at night.

Looking at his data, I had a flashback to our first owl, Assateague, in 2013-14, which also wintered on this bay. Like Assateague, Island Beach’s nighttime locations clustered out in the middle of the bay, more than a third of a mile (.6 km) offshore…where there is no land on which to sit. Zoom in closely enough on his map, though, and you’ll see what I found — a channel marker. Just like Assateague, Island Beach is flying out onto the bay at night and landing on the buoy for a look-see, presumably to pick out a nice, plump duck or gull for dinner.

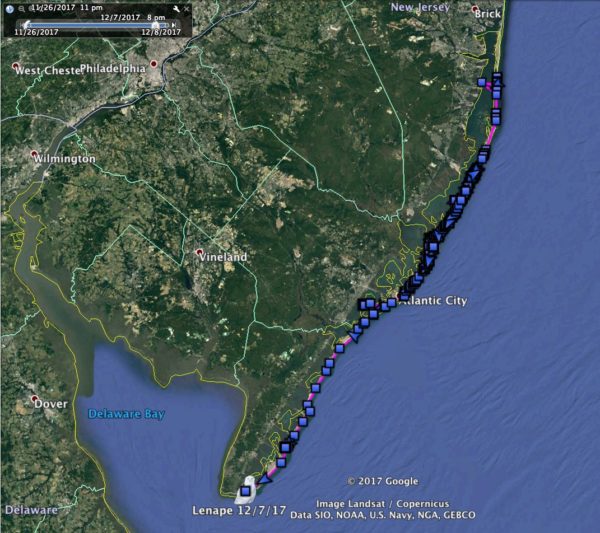

Lenape’s gone as far south as he can in New Jersey. Will he loop north again, or strike out across Delaware Bay? (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)Assateague, Island Beach is flying out onto the bay at night and landing on the buoy for a look-see, presumably to pick out a nice, plump duck or gull for dinner.

Island Beach has stayed put since he was tagged, but the other young male marked at the park, Lenape, moved and kept on moving. In the past week or so he’s flown almost 80 miles (125 km) south along the coast, mostly hugging the barrier islands that frame the Jersey shore. By Dec. 3 he’d reached the mouth of Great Bay, and spent three or four days hunting the marshy islands that make up part of Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge — while making a couple of excursions down the coast a few miles to Atlantic City. From there, he continued down the shore to Cape May, where Thursday evening he was sitting on the beach in front of La Mer, one of the big hotels on the waterfront.

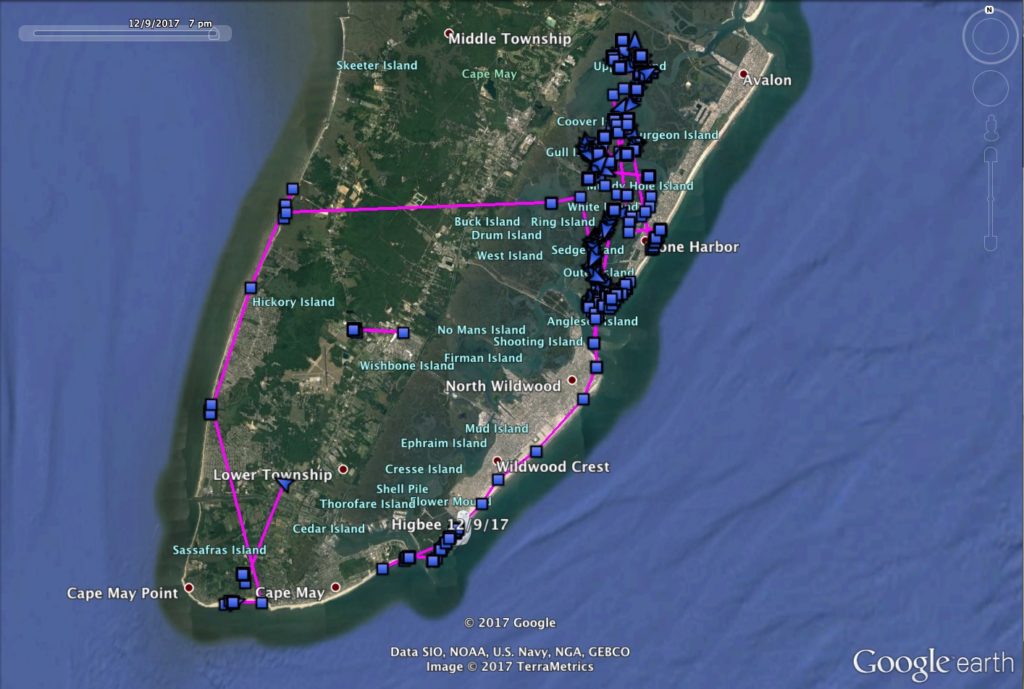

Ironically, Higbee — which was tagged last week at the Nature Conservancy’s South Cape May Meadows preserve, and whose transmitter was underwritten by TNC — moved off the tip of the peninsula, and into the extensive tidal creeks and marshes near Great Sound and nearby back bay areas. That’s rich habitat any time of the year, especially now when a lot of waterbirds are using it. (And it’s also where Hungerford spent part of the winter four years ago.) What’s more, it’s close to a large marsh restoration project the conservancy has been working on for several years. Then on Dec. 9 she looped back south again, using the beach on either side of the Cape May inlet, just a few miles from where she started.

Higbee took the loop-the-loop route, completing a circuit of southern New Jersey. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

One of our research goals this winter was to tag owls as early as possible, to track their initial wandering soon after appearing in the south. As the wide-ranging tracks of many of these birds show, that plan is paying off, and it will be fascinating to see whether (and where) some of these vagabonds finally fetch up for the winter.