Welcome to the 2017-18 winter season for Project SNOWstorm!

As many of you are aware, there have already been an unusually large number of snowy owls reported in the Great Plains, Midwest and Northeast, some as far south as Oklahoma and Virginia. It looks like a very exciting winter lies ahead. We’re ready, and will share more about our plans for this season in the days ahead.We had a little warning that this might be a big season, though, because of reports from the Arctic and subarctic this summer — and we’re pleased to kick things off this season with the following report from up North by SNOWstorm team member Dr. Jean-François Therrien, senior research biologist at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania, who has been studying snowy owls in the Arctic for years with Laval University in Quebec.

Will this winter see a big irruption of snowy owls? The answer depends on where the food was this past summer — and where owls were able to produce a lot of chicks like this half-grown youngster in the distinctive “white mask” stage. (©Audrey Robillard)

Our research and monitoring of the tundra ecosystem continued during summer 2017 on Bylot Island (Nunavut, Canada), where for more than 25 years, my colleagues at Laval University in Quebec and I have been studying snowy owl nesting activities. Our team is pretty unique as it includes expert researchers scrutinizing almost every living organism in the ecosystem, from plants and lichens to insects and spiders, all the way through lemmings, songbirds, shorebirds and geese, and finally to predators like ermine, foxes, seagulls, jaegers and raptors. In addition, a set of weather stations continuously record every possible environmental variable throughout the year while glaciologists and geomorphologists keep track of glaciers and land mass movements. To say that we have the ecosystem under surveillance would be an understatement.

The greatest thing about being part of such an extended team is exactly as the saying goes: The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Because we have colleagues studying in great detail the fluctuations in lemming numbers, we can concentrate in studying the raptors that depend on lemmings — like snowy owls — in detail. And the reverse is also true. By knowing precisely how many raptors nest and how many prey they eat, our colleagues can infer the predation rate that lemmings face. With many emerging pressures facing our environment, such scientific collaborations are crucial in order to understand changes threatening species and ecosystems.

Those of you following this blog probably remember the amazing breeding success that was recorded on our long-term study area of Bylot Island in summer 2014 (116 snowy owl nests) followed by a much slower breeding year in summer 2015 (no nests) and an intermediate year in summer 2016 (five nests). Well, it seems that both lemmings and snowy owls have read the same textbook. Indeed, with a periodicity of about four years, 2017 was supposed to be a quiet one in terms of lemming and raptor numbers on Bylot Island. And so, it was. Colleagues surveying the study area in early June sent a few emails warning us: Very few lemmings, no owls to be seen.” They were right; a grand total of zero snowy owls nested in 2017 on Bylot Island, our main study site.

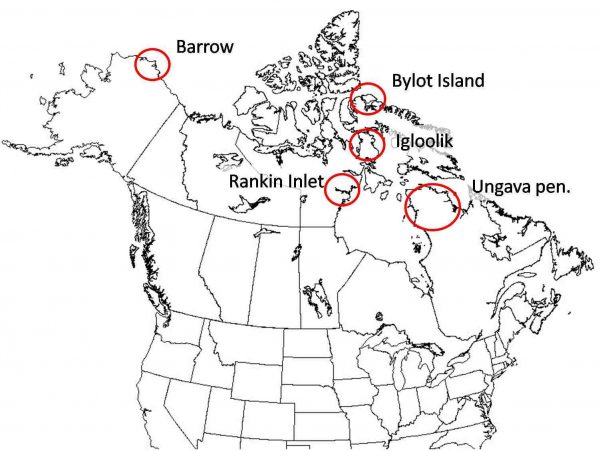

A very similar report came from our colleague Denver Holt, conducting long-term monitoring in Barrow, Alaska: “Lemming numbers very low, not a single snowy owl nest to report.” Although disappointing, this situation is part of a natural phenomenon, a periodic fluctuation in the numbers of both herbivores like lemmings, and their predators. But if not a single snowy owl was reported from our study site — a place that can host more than a hundred nests in a good lemming year — where did they go? Are they breeding somewhere else? Indeed, as many of you now know, we have discovered using satellite transmitters that snowy owls disperse over huge distances annually, and can settle in far distant places to nest where lemmings are abundant. So if snowy owls were nowhere to be seen both on Bylot Island and Barrow, they must have been somewhere!

Five areas where snowy owl breeding activity was monitored this summer — Barrow, AK; Rankin Inlet, Igloolik and Bylot Island, Nunavut; and the Ungava Peninsula, Quebec.

Indeed, earlier this year I received emails from researchers working at two sites in Nunavut, Canada — one team under the supervision of Alastair Franke from the University of Alberta, on Rankin Inlet in the northwest Hudson Bay, and another team at Igloolik, north of Hudson Bay on the Foxe Basin. Both sites reported nesting owls, but the most exciting news came from people surveying a large region in northern Quebec called the Ungava Peninsula.

If that name sounds familiar, it’s because the last time snowy owls nested in the Ungava was in the summer of 2013, just before that massive winter irruption that actually triggered Project SNOWstorm. In fact, that’s where this famous picture of a snowy owl nest surrounded by 78 lemmings came from.

The iconic photo from 2013: 78 dead lemmings and voles surround a snowy owl nest in the Ungava. The owls were back this summer — will there be a big irruption as a result?

Well, it seems that four years later, snowy owls again settled in that region. Wildlife biologists studying caribou covered the region from a helicopter and reported seeing snowy owls in the same area we surveyed four years ago. Our colleagues from a mine company in the region (Glencore-Raglan) also confirmed seeing lots of snowy owls there. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to send someone up there to assess lemming and owl densities as well as their clutch size and nesting success, but this nonetheless indicates that there was some breeding activity across that region.

But the early appearance in recent weeks of dozens of snowy owls in the Great Plains, Great Lakes and Northeast — and as far south as Virginia in the past few days — suggests this could be another very exciting winter in eastern North America.

I’ve said this over and over again: snowy owls have a tendency to surprise us. We’ll have to wait and see how many birds show up at our latitudes, but Project SNOWstorm is already gearing up for perhaps our most ambitious winter season ever. Our team members are poised from the Dakotas to southern Canada and New England, and in the days and weeks ahead we’ll be sharing our plans for this winter season, and the years to come. As always, we’ll keep you updated as the winter of 2017-18 unfolds, but we’re sure it’s going to be thrilling, and will add to our growing understanding of the ecology of these magnificent birds.

5 Comments on “A New Season – and a Report from the Arctic”

That’s a great update, sounds like maybe there will be many snowy owls coming south this season! We’ve seen our first one yesterday (Ontario).

Can verify this, unfortunately I have no photos to back this up. We saw up to a dozen snowy owls (harfangs des neiges) in a group (parliament?) in the region of the Ungava Peninsula this summer. This was on the mine site Canadian Royalties south of and next door to the Raglan-Glencore mine property.

There have been Snowy Owls at our Airport last winter and the years before. People need to be aware of the need sof the long distance haulers as they make it hear or to other parts of our state. Be sure to look from afar and do not disturb the owls, they need all the strength and resources available to them. Energy is vital and they give us so very much to see and learn. Thank you for the valuable information and the steps you take for the Owls.

Several years ago I read about Snowy Owls which were killed at one or more of the NYC area airport. I also read that Snowy Owls are captured at Boston’s Logan Airport. These birds are relocated. Have you contacted the PANYNJ and the people who run Boston’s airport?

Norman Smith from Mass Audubon, one of the founding members of SNOWstorm, is relocating owls at Logan Airport as he’s been doing since 1981. We’ve reached out to a number of other airport managers and federal wildlife officials at regional airfields, many of whom have cooperated with us in the past and expect to do so again this winter.