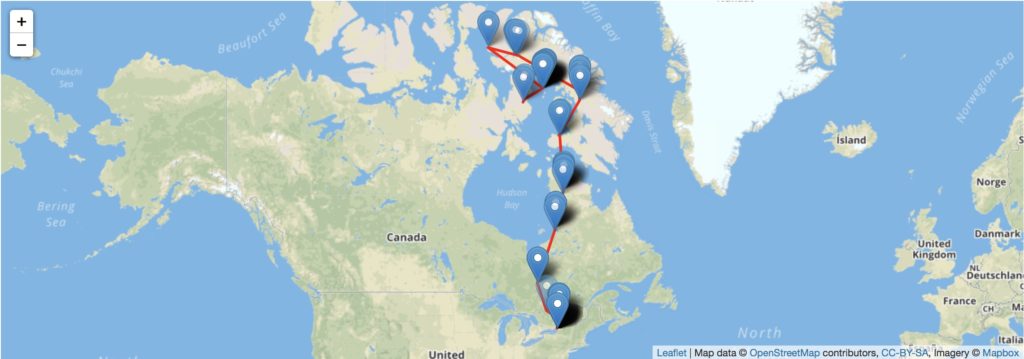

Otter’s summer and autumn migration through the Canadian Arctic is laid out in exquisite detail by almost 11,000 GPS locations. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Ever since we started Project SNOWstorm in December 2013, we’ve relied on an exceedingly cool piece of technology — the GPS/GSM transmitters made by Cellular Tracking Technology.

As longtime SNOWstorm fans will know, these devices log locations from the GPS satellite system, but transmit those data to us via the GSM cell network. That means that while the snowy owls are down here in temperate latitudes we get regular downloads of the tagged birds’ locations, but once they leave cell service — although the units continue to record positions — they can’t send them to us until the bird migrates south again into cell range, usually the next winter. That’s what happened already this fall with three returning owls, as we detailed in our last post.

Unlike cellular-only transmitters, the hybrid units like this one on Seneca have an external antenna that allows the device to communicate with the Argos satellite system. (©Aaron Winters Photography)

But last winter, we had a chance to field test CTT’s experimental new Argos hybrid transmitters. In addition to the standard GPS/GSM capability, these units can also communicate with the Argos satellite system used for standard wildlife telemetry, so we can keep track of a tagged bird even in the Arctic. Last winter, Tom McDonald deployed two experimental hybrid units on snowies in upstate New York — birds we nicknamed Otter and Seneca, both adult males.

Seneca’s Argos link quit fairly early; we now suspect the exterior antenna that the Argos system requires, which CTT made fairly light to save weight, wasn’t quite tough enough to withstand fiddling from a large owl — and we know from photos taken at the time that Seneca was tugging at his. Whatever the reason, the Argos link broke down in March, and while Seneca’s regular GSM transmitter continued to work just fine (it has no external antenna), once he left cell range in May we lost track of him for the summer.

The transmitter on Otter, also an adult male, seems to have held up better — or maybe it was because snowies, like all animals, are individuals, and he simply wasn’t as rough with his antenna as Seneca. Whatever the reason, we were able to follow Otter’s movements north after he left cell coverage on May 2, when he was by Lake Tamiskaming on the southern Ontario/Quebec border.

As programmed, Otter’s Argos linked connected once a week on Mondays with the Argos satellite network orbiting 528 miles (850 km) overhead. A normal Argos sat-transmitter (known as a “platform”) sends repeated signals to one of the seven satellites that pass over each inch of the globe six to 14 times a day, depending on latitude. The satellite measures the Doppler shift of the platform’s frequency in those repeated signals as the satellite approaches and then moves away from its location on the ground, which an algorithm converts to a calculated position. The accuracy of an Argos position can vary dramatically, though, and sometimes no location can be calculated at all.

What’s cool about the hybrid units we’re using is that while they are in contact with the Argos satellite, the transmitters also send a data packet of the last 30, highly precise GPS locations that it had stored — so regardless of the quality of the Argos position, we get a very accurate snapshot of exactly where that owl is on the day of transmission.

The Argos interface shows Otter’s weekly transmission locations from early May through the end of September, when he was still on Rowley Island. (©Project SNOWstorm, CTT and ESRI)

So once a week through the spring and summer, we were able to track Otter as he moved up the east side of James and Hudson bays, and across Hudson Strait on May 22 to the Foxe Peninsula on Baffin Island, the fifth-largest island in the world. Over the next three weeks he continued to move almost 1,500 km (nearly 1,000 miles) along the southern shore of Baffin Island, finally reaching the Gulf of Boothia June 15.

Uninhabited Rowley Island, 71 km (44 miles) long, was Otter’s summer home. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

From there, Otter turned south across the Melville Peninsula and out to Rowley Island, an uninhabited island in the Foxe Basin, where on July 8 he settled in for the next three months. In that time, he was using an area of about 120 sq. km (about 45 square miles), suggesting that he wasn’t provisioning a nest. That would make sense, since colleagues of ours at Igloolik, just to the west, and Rankin Inlet on Hudson Bay, reported a total lack of snowy owl nesting activity this summer in that part of the Canadian Arctic.

We were able to follow Otter’s activities through September via his Argos connection, but his last transmission was Sept. 30; after that, silence. Any number of things could have happened, including Otter’s death in a manner that disabled his transmitter, but the most likely explanation was that his antenna finally failed, as had Seneca’s. All we could do was wait to see if he returned south, when his GSM cell modem would connect. (Meantime, CTT has significantly beefed up its antenna design as a result of these experiments.)

That’s all interesting enough. But as I was preparing to post this update this morning, who should phone home but Otter! His GSM unit dialed up at 8 a.m., downloading an amazing ~11,000 GPS locations that flesh out all the details of his last six and a half months of travel. After leaving Rowley Island at the end of September, he skirted the western edge of Hudson Bay, crossing James Bay in early November, lingering for a time near Desmaraisville, QC, before pushing on the past few days. At dawn today he was east of Saint-Jérôme, about 30 km (19 miles) north of Montréal.

But don’t take my word for it — Otter’s map has already updated with all of his data, so go explore for yourself, and see what our first hybrid owl has been up to. And keep your fingers crossed that Seneca returns soon, too, so we can get the story of his summer.

4 Comments on “Otter’s Excellent Summer”

November 26th and 27th snowy owls Mower County Minnesotaearliest that I seen themtried to see if they had transmitters on them but could notexact location six hundred and 50th Avenue and 300th Street

Crossing our fingers for Seneca’s return!! Otter did move around quite a bit, so cool to see. Thanks!!

It is so sad to see these poor creatures encumbered by these tracking devices. As a life long avian tender, I know how intelligent birds can be. These animals are not” projects” as you state. These are creatures who are highly intelligent and are capable of a range of emotions. Your company treats them like a “tool” which they are not. Their plumage is vital to their survival yet you staple some electronic device to their backs with no concern of how it may affect them in their daily lives. I have seen parrots destroy flight feathers in an attempt to remove tagging and injure themselves in an attempt to remove banding. I would love to see you and the rest of these selfish douchebags with a transmitter stapled to your back. I would not donate a dime to project owl torture. If you really want to help snowy owls, there are other ways than throwing chains on them like some slave

I’m sorry you have such a negative perception of the work we do; we believe (and our experience bears out) that the information we’ve gained from our tracking studies provides valuable guidance for conservation action on a species that is in the crosshairs due to climate change.

I must also correct a number of misconceptions in your comment — we are not a company, but a nonprofit whose team members donate their time. Nor do we “staple” anything to the owls. The transmitters, which weigh less than 3 percent of the owl’s body weight, are fitted using smooth, soft Teflon ribbon that goes around the bird’s body like a backpack, down against the skin. Raptor researchers use woven Teflon because in addition to being extremely tough, it is smooth and doesn’t rub or cause abrasions. In cases like the owl we nicknamed Buckeye, recaptured last month after four years of wearing one of our transmitters, we can see that neither the unit nor the harness caused any issues.