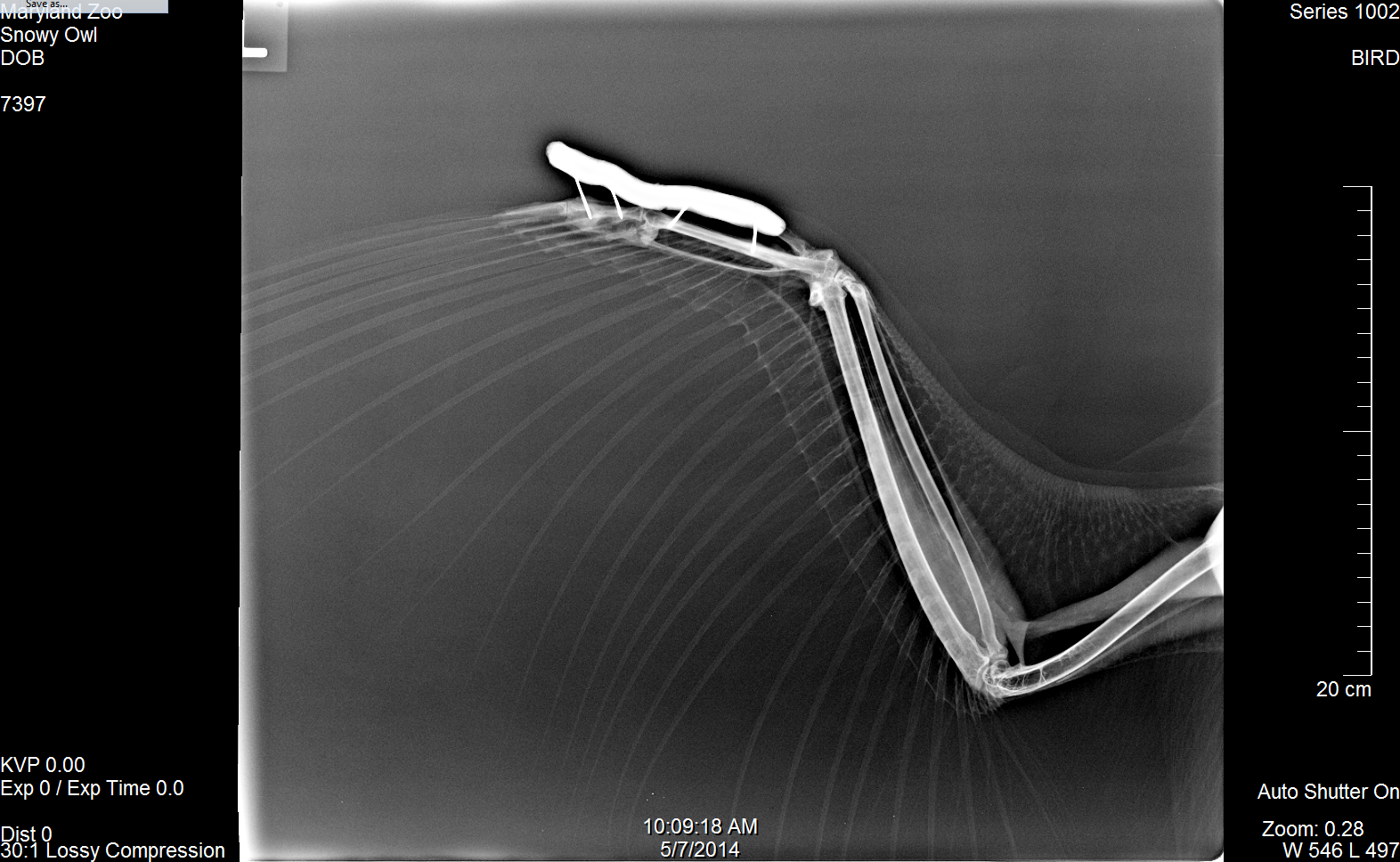

Delaware — an injured owl rehabbed for nine months at the Maryland Zoo, flies free in December 2014. Project SNOWstorm tracked her movements for a month after her release to confirm that she was hunting normally, then retrapped her and removed her transmitter. (©Allen Sklar)

First things first; it’s clear that Covid-19 is upending normal life for everyone, and we hope everyone in the Project SNOWstorm community is taking the situation seriously, following expert guidance, and staying safe. This is a new and largely unknown time for all of us.

Dr. Ellen Bronson, with a non-snowy owl patient.

That said, we’re still working hard on snowy owl research, and will continue to keep you posted; after all, the natural world provides a powerful antidote to anxiety. Most of the news we share on the SNOWstorm blog involves our tracking work — but that’s far from the only research our scientists are pursuing. We have a crack team of wildlife veterinarians who have, from the start, been looking into the health of snowy owls. Some of that work entails necropsying those owls that are found dead after mishaps, injuries or disease; in other cases, they are able to study samples from live snowy owls collected by our field teams, and they’ve been instrumental in working with rehabbed snowies. This time, we’re pleased to bring a report from Dr. Ellen Bronson, a veterinarian at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore who is part of that effort, to let you know what they’ve been up to in the lab. Here’s Dr. Bronson.

— Scott Weidensaul

* * * * *

Veterinary technicians at the Maryland Zoo, working on blood and tissue samples. (©Maryland Zoo)

Partners and Background: Beyond the goal of learning more about the movements, locations and behavior of the snowy owls in Project SNOWStorm, a team of veterinarians has been investigating the health of the owls since the start of the project. That small but dedicated group consists of myself and my veterinary team at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore; Dr. Cindy Driscoll, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources state fish and wildlife veterinarian; Dr. Erica Miller, wildlife veterinarian at the University of Pennsylvania; Dr. Sherrill Davison, associate professor of avian Medicine and Pathology at the University of Pennsylvania; and Dr. Lisa Murphy, toxicologist and director of the Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Laboratory System’s New Bolton Center Laboratory, and co-director of the Pennsylvania Wildlife Futures Program, both located at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

Previously, because of scant information on the health of snowy owls during irruptions, many people assumed that the birds that came far south were typically young males in very poor condition. During the first year of the project, 2013-14, we took as many blood samples from live birds as possible and performed necropsies on dead birds

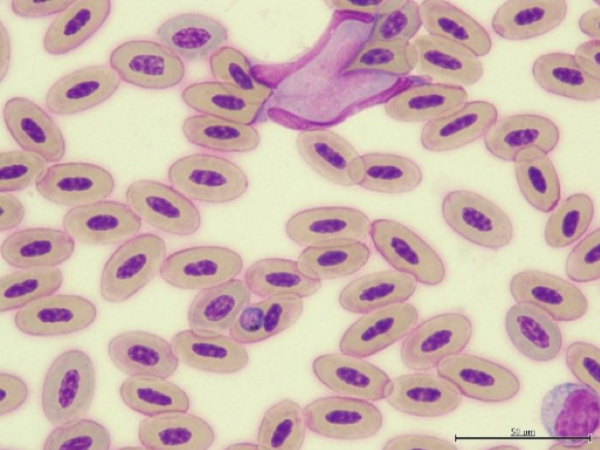

A snowy owl blood smear with showing blood parasites, including Plasmodium relictum (avian malaria; the round organism in red blood cell just below center) and Leukocytozoon (the large, butterfly shaped parasite top middle). (©Maryland Zoo)

submitted from northeastern U.S. states. Our initial results revealed that most of the irruptive snowy owls were indeed young birds, but that males and females were evenly split, and the live birds were overwhelmingly healthy and in good body condition, as were many of the dead birds.

Since that year, we have continued to collect as many blood samples as we can on live snowy owls across the continental U.S., using the broad network of SNOWstorm collaborators in many states, from as far west as North Dakota, north to Maine, south to Maryland and everywhere in between. Blood samples are collected when the snowy owls are already in hand for transmitter placement or banding, taking advantage of this huge opportunity to learn even more from these birds.

Maryland Zoo veterinarian Annie Rivas and SNOWstorm co-founder (and MD Dept. of Natural Resources biologist) Dave Brinker examine Baltimore, when the owl was tagged in 2015. (©Maryland Zoo)

Samples: Bloodwork is typically shipped by collaborators to the Project SNOWstorm Biobank at the Maryland Zoo and processed by our registered veterinary technicians. Basic health assessment from blood samples includes documenting complete blood counts (CBCs), chemistry profiles (an indication of organ function), and blood parasites.

A portion of the blood is also examined at the University of Pennsylvania for heavy metals, rodenticides, pesticides, and other contaminants. This information will be collated with the tissue toxin screens that we are performing on dead birds to assess the overall toxin load of snowy owls as they travel from the Arctic to the southern reaches of their ranges and back.

Because snowy owls migrate so far through such a variety of landscapes, they provide unique information about the toxin loads in the environment and how they change over time.

Continued Efforts: The information we are gleaning from this portion of the project is thrilling and one-of-a-kind and could not be done without two major factors.

First, the public donations to Project SNOWstormmake it all possible, and for that we are endlessly grateful. And secondly, we wouldn’t have the samples to run at all without the amazing network of people that volunteer their time on this project. Biologists, banders, veterinarians, veterinary pathologists, and rehabilitators have all come together to gather this information that will continue to grow over time and continue to yield vital information about snowy owls and their environment.

As the only Project SNOWstorm collaborator based at an accredited zoo, it has been the greatest pleasure to be able to transfer my many years of experience caring for the health of zoo-housed snowy owls to their wild counterparts. The excitement of examining that first free-ranging snowy owl during the mid-Atlantic irruption of 2014 is something that is hard to put into words and has not decreased one bit in the sixth year of Project SNOWstorm.

A radiograph of Delaware’s wing showing pins and fixator that held the damaged bones in place while they healed. (©Maryland Zoo)

Delaware, out of rehab and ready to be released by SNOWstorm cofounder Steve Huy.

4 Comments on “Project SNOWstorm’s Veterinary Health Assessment Collaborative”

A wonderful article that I really enjoyed reading.

Heartfelt thanks to all who participate in these programs.

Thanks for the very interesting update on another side of team SNOWstorm work with snowy owls.

Thank you so much for all the great work you do! Also, nice to know that most of the owls were in good physical shape!

You people are amazing! Thanks for everything you are doing to help the Snowys!