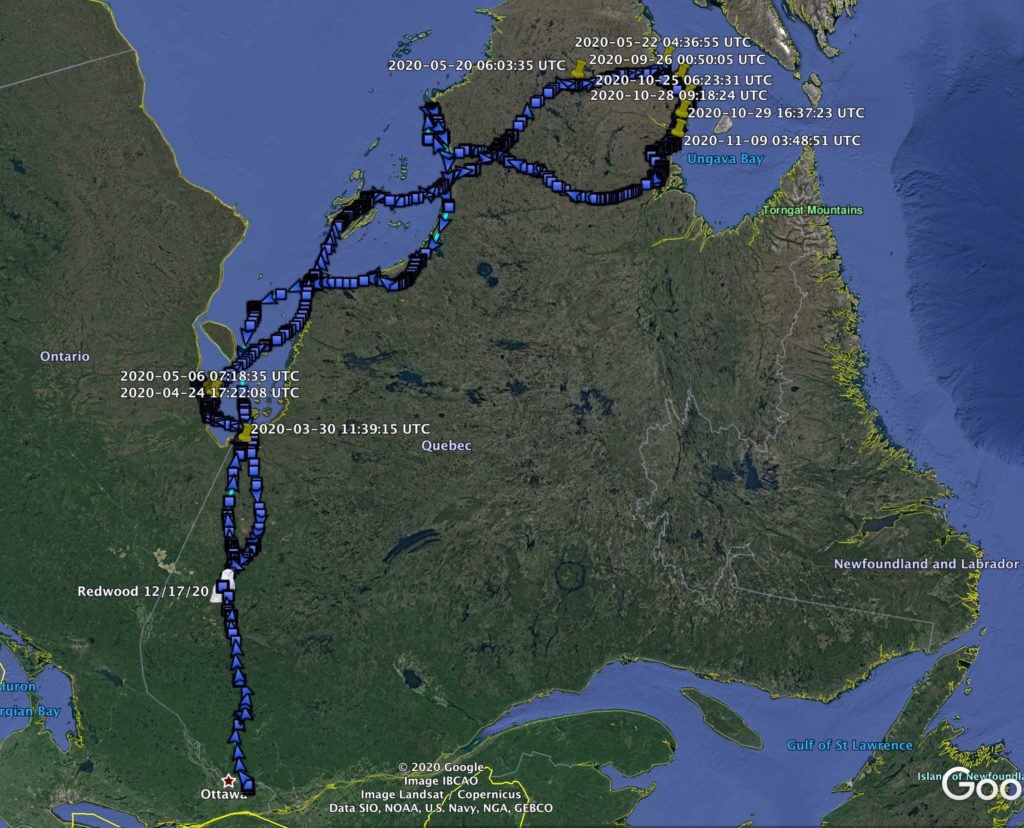

Redwood’s summer travels. up to the northern Ungava and back. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

There are few more exciting moments for us here at Project SNOWstorm than when an owl that’s been out of touch for months checks back in again. So we were pretty jazzed last week when the transmitter carried by Redwood — a dazzlingly all-white adult male snowy tagged last January in upstate New York — connected for the first time since late March.

And connect it did, uploading more than 11,000 GPS data points that paint an incredibly detailed picture of this owl’s movements and life over the past eight or nine months.

Tom McDonald with Redwood, just after he and Melissa Mance-Coniglio captured this breathtaking adult male in New York last January. (©Melissa Mance-Coniglio)

Redwood was trapped Jan. 2, 2020, by Tom McDonald and Melissa Mance-Coniglio in Jefferson County, NY, at the eastern extreme of Lake Ontario. That’s where the bird spent the winter, including a few days (pretty tense for us) when he was on the airfield at nearby Fort Drum. In early March Redwood started north, and by March 21, his last connection, he was in southeastern Ontario near Ottawa.

From there, we now know, he moved rapidly north, reaching James Bay by the end of the month, and migrating north to the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay by mid-May. He then cut diagonally northeast across the Ungava Peninsula, and a week later, by May 23, he was near Cap Hopes Advance, which forms the juncture of Ungava Bay and Hudson Strait.

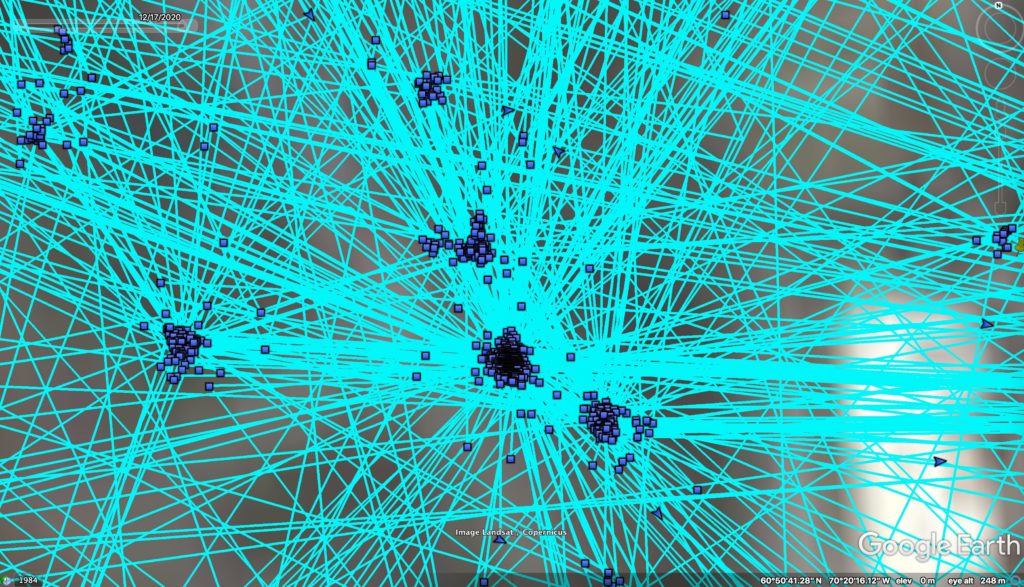

And that’s where he stayed for the next four and a half months, occupying a territory of about 4,000 ha (about 10,000 acres) — and within that, he really zeroed in on a small area of just 15-20 ha (30-50 acres), in which there is a single main focal point surrounded by four or five other locations where his GPS points cluster.

That central cluster of points is almost certainly Redwood’s nest, surrounded by perch sites from which he could keep guard and hunt. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Because they’ll spend six weeks or so incubating and brooding in one spot, it’s relatively easy to ascertain breeding activity for a tagged adult female owl, like Dorval earlier this year. Males are not tied as tightly to the nest, but Redwood’s pattern strongly suggests he was provisioning and protecting a mate and their chicks. That central point is likely the nest, which he watched and guarded perch sites within a few hundred meters.

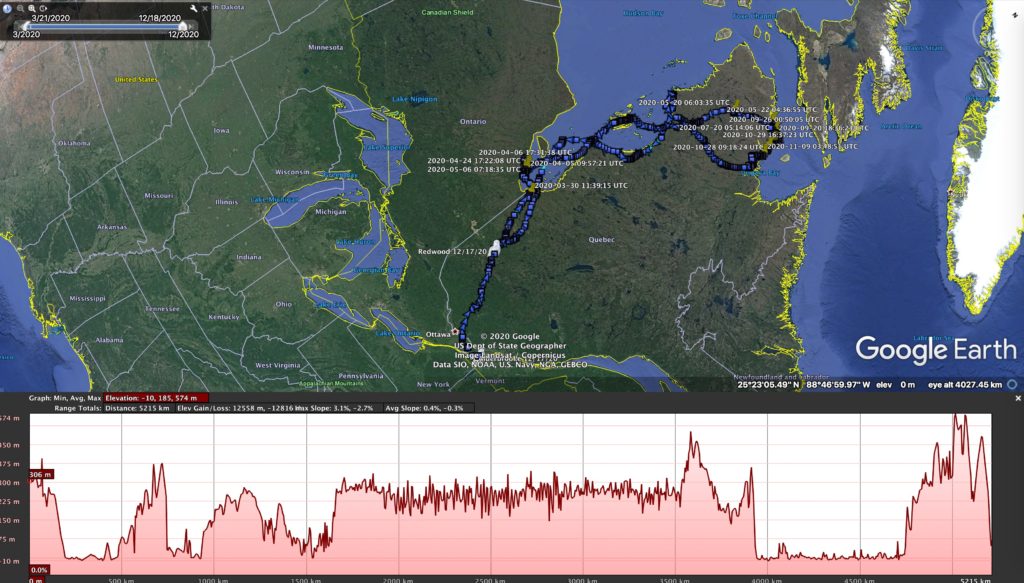

Redwood stayed on his summer territory until early October, then drifted east to Ungava Bay, meandering slowly south through the end of November. He then flew due west across the Ungava Peninsula, reaching Hudson Bay on Dec. 2. After a short, abortive flight north, he moved around the rim of Hudson Bay and south across the frozen expanse of James Bay. Dec. 15 he left the ice and entered the boreal forest, which for a tundra species is an alien world, and two days later he checked in near the small town of Saint-Dominique-du-Rosiare, in Abitibi Regional County Municipality of southwestern Québec. That’s about midway between James Bay and the Ottawa River Valley, often the first stop for southbound owls exiting the boreal woods.

The graph shows the elevation profile for Redwood’s migration and time on the breeding grounds (the long, even section in the middle). The very low sections, especially on the right, are when he was on sea ice on James or Hudson Bays, barely above sea level. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

In all, between March 21 and Dec. 17 Redwood flew 5,200 km (3,230 miles). As with most snowy owls, he migrated mostly in short stages, stopping frequently and only rarely reaching high altitudes — the peak flight for him was during his northbound passage across western Québec, when at one point during a three-hour flight he was 574 m (1,883 feet) above the ground.

Now we’ll be very curious to see where Redwood ends up for the winter. We’ve found that while juvenile and subadult snowies shift — sometimes quite dramatically — from one winter to the next, once they reach maturity they tend to become quite faithful to their wintering locations. Redwood, is a fully adult bird. Will he come back to Jefferson County, NY, or surprise us by finding a new wintering site?

That’s it for today, but look for a fresh update in a day or so that will catch you all up on the other owls we’re following this winter — Columbia, Stella and Dorval.

Stella checked in Dec. XX after being off the grid for XX days

5 Comments on “Redwood’s Return”

What a handsome boy!

Look forward to these exiting updates. While we can’t travel at least the birds can!

Seeing these kinds of data presented here really brings home the value of the work you are doing, and the critical ability of technology to gather data that humans simply cannot. The lives of these magnificent birds are fascinating.

I have been thinking of Redwood and so excited today to get the news that he is okay ! Redwood is absolutely beautiful . Magic

Oooh this is SO exciting! I love knowing that Redwood nested and is coming south again!!

Thank you!

JZ