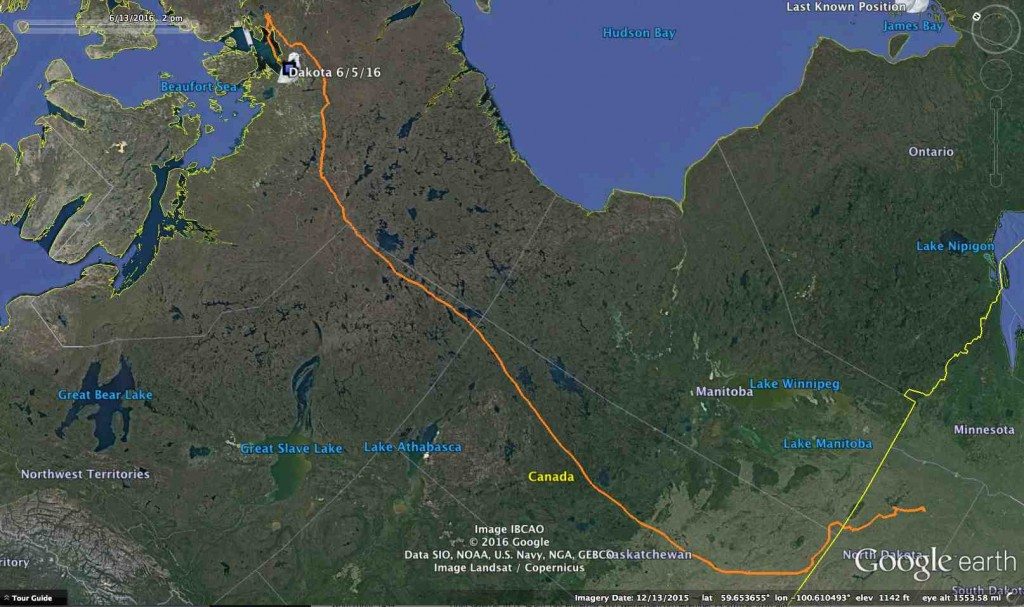

Dakota’s northbound migration in April and May (north to the upper left), from North Dakota to the central Canadian Arctic. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

While we’ve been looking back this past week at Project SNOWstorm’s accomplishments, we’ve also had some exciting new developments behind the scenes: the return of two of our favorite owls. Hardscrabble and Dakota are back — and Dakota, it appears, has a bun in the oven.

On Nov. 10, my wife and I had just been seated at a restaurant for a rare evening out when my cell phone buzzed. I glanced at the text, and suddenly lost all interest in the menu.

“CTT Data Update: Unit #27235116 (Dakota – ATY Female) has checked in,” it read.

Dakota, just after getting her transmitter last February in North Dakota. This adult female was originally banded Jan. 2014 in Michigan. (©Dave Brinker)

Dakota is an adult female tagged Feb. 1, 2016, by Matt Solensky and Dave Brinker in eastern North Dakota, and originally banded in January 2014 at the Saginaw, MI, airport. Plugging in the coordinates in the message, we saw that she was then just west of Regina, Saskatchewan, close to her last reported position back in April as she was heading north. Her transmitter’s solar-powered battery was pretty low — typical of owls that have just come south from the Arctic, where by November the sun is mostly a memory — so we only got a small portion of her backlogged data that night.

(Just a reminder: Our transmitters only communicate with us via the cell network, so once the bird leaves the U.S. and southern Canada in spring, we lose contact with them. But the units continue to store GPS locations as regular as clockwork, and when/if the owl comes south the next winter, those stored data are uploaded and we discover where the bird has been in the past eight or nine months.)

The next time Dakota checked in, her transmitter took up a special duty cycle designed to maximize battery recharge and rapid data retrieval. But we also noticed that she had turned around and was heading north again, back out of cell range. After that, she disappeared for a week. Then two. Then three.

It was hard not to wonder if she was pulling a Buena Vista. Last fall, Buena Vista — our second tagged owl, caught in December 2013 — showed up on the edge of the cell network in Manitoba, sent one short transmission, and then disappeared again, apparently passing the winter somewhere out of cell range.

But on Dec. 12, Dakota checked in again, this time south of Regina — probably pushed there by a huge blizzard that finally snapped a stretch of weirdly warm weather in the Canadian prairies. She started sending us regular chunks of her backlogged data, and we could follow her springtime progress north in May up through Saskatchewan, along the eastern edge of the Northwest Territories and into Nunavut. New data segments showed she had headed up the Boothia Peninsula, an area where several of our other tagged owls have summered.

On May 18, Dakota did a U-turn on the Boothia Peninsula and headed back south for almost 200 km — and then seems to have found a mate. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

On May 18, she reached a point some 2,430 km (1,500 miles) north of her winter territory — and turned around. She backtracked, as a number of tagged birds have done, moving 179 km (110 miles) down the still-frozen Rasmussen Basin and settling in an area around 67 degrees north latitude along Chantrey Inlet, south of King William Island and about 80 km (50 miles) north of the Arctic Circle.

We were really paying attention now. Dakota was a full adult, and we knew there was a chance she could be the first tagged SNOWstorm owl to send us nesting data. Or would she find a lack of lemmings in her chosen area and spend the summer wandering across thousands of kilometers, footloose and responsibility-free, like other tagged birds had done?

The data were coming in chunks of 300-400 GPS points, about a week’s worth at a time. The last week of May, she had localized in an area of a couple square kilometers — and by the second week of June (the data for which came in Wednesday night), she started burning a hole in the map, hundreds of GPS points piled on top of one another as she became effectively stationary. Dakota was on a nest.

With hundreds of GPS points within a few meters of each other, this data download was unambiguous — Dakota was on a nest by the second week of June. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

So far as scientists know, snowy owls pair up on the breeding grounds — and satellite tagging of breeding adults in Canada, Alaska and Russia has shown they can be highly nomadic, so they likely form a new pair bond with a new mate each year. The nest is a bowl scraped in the tundra, usually on a high, wind-raked spot where the snow is blown away. As with most owls, the female begins incubating when the first egg is laid, with additional eggs added every two or three days. Clutch size depends on the abundance of food, largely lemmings, and can range from three to five at the low end, to seven to 11 eggs (sometimes more) when lemmings are at historic peaks.

We won’t be able to tell those details from Dakota’s recorded data, of course — but assuming her nest was successful, we should be able watch how her movement patterns change as the eggs hatch, the chicks age and begin to wander away from the nest, something young snowies do as early as three weeks of age. This will be a first for us, and given the extreme precision of movement detail we get from our CTT transmitters, should be illuminating.

* * * * *

We did have one scare. While we’re not getting Dakota’s current data (that will come after we catch up on the backlog) we do get “Current location” coordinates — and last week, two transmissions in a row were in exactly the same spot.

Hmm. Could be that the owl just has a favorite perch, though Google Earth showed no utility pole or other likely feature, just the edge of an empty wheat field near the Saskatchewan town of Francis. The other obvious possibility was that she’d been injured or killed.

What to do? Fortunately, SNOWstorm has a lot of friends. We contacted fellow snowy owl researcher Dan Zazelenchuk in Saskatchewan, who quickly contacted a colleague of his, biologist Dan Sawatzky — who was almost immediately in his truck and headed to Francis. Dan spent several hours in the cold and snow exploring the area where Dakota’s last fix had been, even kicking through snow drifts in case they hid a carcass. No sign of Dakota. “But I did locate where the bird was probably sheltering from the wind,” he reported, “a small pile of straw and weeds along a north/south quarter section line, a typical location where I have often noticed SNOWs sheltering on windy days.”

The next night, Dakota checked in on time, from a location a kilometer or two away. It had been a false alarm and she was fine, but that doesn’t diminish our gratitude to Dan for checking.

* * * * *

Hardscrabble, after getting his transmitter last winter. (©Tom McDonald)

The other returning owl so far is Hardscrabble, an adult male tagged Feb. 22 last winter by Tom McDonald on Cape Vincent, NY, at the eastern end of Lake Ontario. Coincidentally, Hardscrabble and Dakota were both among the last owls to lose contact in the spring — Dakota on April 22, and Hardscrabble on April 28.

He checked in last Friday morning, with a very low battery and only a bit of his backlogged data, but his current location put him about 100 km (62 miles) west of Ottawa, Ontario, in farmland along the Ottawa River near the hamlet of Cobden.

Time to call more friends. I quickly got in touch with longtime SNOWstorm supporters Patricia and Dan Lafortune in Ottawa; they’ve kept an eye on some of our owls in southern Ontario in the past, and I thought they might have an interest in trying to find Hardscrabble.

“My sister-in-law has a farm house in Cobden!” Patricia quickly replied. She and Dan headed west the next day, and after several hours of searching, just at dusk they spotted a snowy owl on a utility pole. It was Hardscrabble, his backpack transmitter visible.

Hardscrabble surveys the farmland of the Ottawa River valley last week. (©Dan and Patricia Lafortune)

Hardscrabble checked in again last night, and took up the new duty cycle configuration, which should allow his battery to recover during these shortest days of the year, and give us increasing amounts of his backlogged data. All we can say at this point about his spring and summer is that at the end of April he was heading north along the eastern edge of James Bay, and that as of last night remained in the Cobden area — but Patricia and Dan were out looking for him again today, armed with the latest GPS location and their cameras.

Meanwhile, we have transmitters ready and teams looking to start tagging new owls in North Dakota, New Jersey and Maine. We also won’t be surprised if additional returnee owls start showing up — several birds last winter, like Baltimore and Century, didn’t arrive until late December (and others, like Buckeye, considerably later than that).

But in the meantime, have a great holiday, everyone, and thanks for your continued support — it means everything to those of here at Project SNOWstorm.