For almost 30 years, Tom McDonald has been chasing snowy owls and their secrets across northern New York. Today, he is an integral part of Project SNOWstorm. (©Aaron Winters)

This is part of a periodic series on influential and pioneering snowy owl researchers, on whose work Project SNOWstorm is building.

* * * * *

Although Project SNOWstorm is just marking its fourth birthday, we’re fortunate to have some of the most experienced snowy owl researchers in the world as part of our core team.

One of the best is Tom McDonald. Born in 1950 and raised in Rochester, NY, Tom studied mechanical engineering in college and was fascinated by anything that flew, from rockets and airplanes to birds and butterflies. With a pilot’s license under his belt, and a keen love for the outdoors, he moved West in the mid-1970s, managing a warehouse for Kraft and spending his free time birding, hiking, hunting, fishing and flying.

“I lived on top of a mountain in a log cabin for eight years with no running water or viable heat source (I survived the winters with a small kerosene heater, a full wardrobe of wool garments and a large heated waterbed),” Tom recalls. He combined his interest in birds and his engineering background, designing traps for researchers at the Colorado Division of Wildlife, and built a radio-controlled bow-net to catch golden eagles for Dr. Frank Craighead, one of the famous Craighead twins who studied raptors, grizzly bears and many other species in the northern Rockies.

In 1985, Tom moved back to Rochester, where he joined Braddock Bay Raptor Research as a volunteer, cutting net lanes, designing and building hawk blinds and traps, and eventually running their Payne Beach trapping blind for many years.

Tom with a pure white male in his early days of studying snowies. (©Tom McDonald)

“Although I have banded thousands of hawks, owls were always my favorites. I saw my first snowy owl near Rochester in the mid-1980s and immediately fell in love,” Tom said. He read everything he could find about snowies in the scientific literature, but one thing he read repeatedly made no sense: That many snowy owls starved to death during irruption years.

“The math failed to add up for me. If most of these juvenile owls starve to death, why do we still have snowy owls? Couldn’t these owls find a rodent or rabbit somewhere between the tundra and Rochester? And if they were in poor condition when they left the tundra, why fly 1,500 miles to die here? More importantly, where did they get the energy to fly that far?”

Tom carefully fits a SNOWstorm transmitter on Orleans, an adult female he tagged in 2015.

So Tom started studying snowy owls himself, launching Project SnowyWatch in 1989, with advice and support from Norman Smith in Massachusetts (another long-time snowy owl researcher was, like Tom, a founder of Project SNOWstorm). He designed remote-controlled bow-nets for capturing owls, banded and color-marked them to track their movements and survival in upstate New York. And he put in time — an incredible amount of time.

Tom changed his shift at the International Paper warehouse where he worked from days to the 3-11 p.m. evening shift so he’d have more time to hunt for owls. He bought an economy car to stretch the funds he had for travel and fuel. Each day, he was in the field from 6 a.m. to a few hours before his shift started. Two days a week Tom covered the south shore of Lake Ontario from Rochester west to Buffalo, and another two days he’d scour the shore from Rochester east to Oswego, Fair Haven and Sodus. The fifth weekday was devoted to chasing birds outside his core area, based on tips from the public.

On weekends he would be out the door at 3:15 a.m., heading east to the Cape Vincent and points east along the St. Lawrence Seaway, arriving by daybreak when the owls would still be hunting. He drove through lake-effect blizzards and icy roads, often putting 700 or 800 miles on his car in a weekend. He searched, trapped and banded seven days a week from mid-November through late March, winter after winter — longer in irruption years.

“I outfitted myself with top-of-the-line winter clothing, including boots that were comfortable down to -100F, because winters in northern New York can see temps drop to -30 to -40F,” Tom said. “I bought a special engine heater plug to keep my car from freezing at night on the weekends up north. On weekend sleep-overs, I closed off one bedroom of my frozen cottage at Black Lake, N.Y. I used an electric blanket to thaw the bed mattress and relied on a small portable electric heater to keep the room at 50-degree sleeping temperature.”

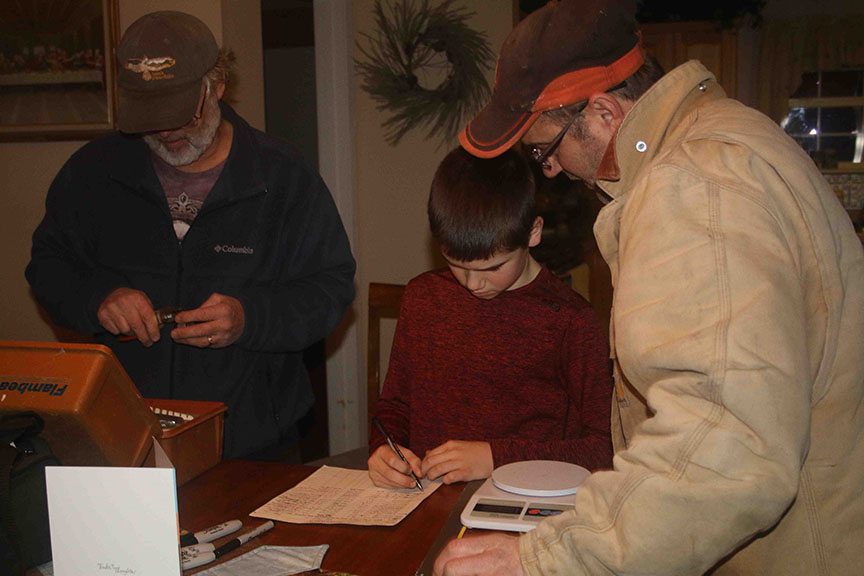

Tom prepares to process and tag an owl in the home of the DuBois family in upstate New York — just one example of the lasting friendships he’s made with landowners in three decades of studying snowy owls.

“Some of the most gratifying moments of my long indenture came as a result of sharing my personal trapping and banding experience with others in the field,” Tom said. “This includes land owners and their families and the locals. I can’t begin to tell you how wonderful it is to bump into a six-foot, four-inch mountain of a man telling his 6-year-old son about how I put a snowy owl in Daddy’s hands 20 years ago. And how he has kept a vigilant watch for snowy owls every year since then.”

Over the years, Tom put 450,000 miles on his car, and banded more than 500 owls (not including recaptures), averaging about 900 miles per owl. He invested something more than 15,000 hours in the project, and tens of thousands of dollars out of his own pocket, but it was worth it.

Tom released one of the more than 500 owls he’s banded in almost 30 years of snowy research. Project SNOWstorm is proud to count him among of its founders and core team members.

“I have been immensely blessed to share wonderful personal and working relationships with other snowy owl researchers like Norman Smith and members of the International Snowy Owl Working Group. Braddock Bay Raptor Research, fellow birders and birding organizations in Rochester have been incredibly supportive of my work through the years.”

“Finally, I feel honored to be part of the Project SNOWstorm family of fellow researchers and friends, who have come together from many disciplines in a selfless way to organize a research project singularly dedicated to the snowy owl,” Tom said. “SNOWstorm has allowed me to accomplish things that I could only have dreamt of doing, including providing GPS transmitters that have already validated some of the theories of snowy owl movements and daily life cycles. It’s helping to answer many of the questions that I have long been asking. Why are the snowies here? What environmental factors are affecting their movements and health? How large an impact is climate change having in their breeding cycles? And many more.”

“I have dedicated 29 years of my life to snowy owls. I will forever love them, for I intimately share their nomadic wanderlust and individuality. We are inseparable.”

* * * * *

(We’re honored to have Tom as a friend and colleague. And an interesting postscript to Tom’s story: Back in Rochester, he encouraged a bird-mad teenager named Mike Lanzone to tag along on some of his trapping expeditions. Mike went on to become a highly skilled raptor and passerine bander, and is now noted golden eagle expert. He also started his own company, Cellular Tracking Technologies, to manufacture the GPS/GSM transmitters he and his colleagues use to track the birds. Mike was one of the founders of Project SNOWstorm, and CTT still provides all the transmitters we use, at the company’s own cost — an in-kind donation worth more than $100,000 and counting.)

3 Comments on “On the Shoulders of Giants: Tom McDonald”

Thanks for the glimpse into Tom McDonald’s extensive snowy owl and raptor research career. We were so lucky to meet him last winter!!! Congrats on Hilton, the first of this season!

I marveled at the photo of the pure white Snowy. Luecistic? Albino?

I’m something of a student of leucistic Red-tailed Hawks, where the color anomaly is reasonably common. (Trapped, studied a white adult.) Any other reports of leucistic Snowies? Any understandings of genetics and occurrences of such. (Leucisticism is not albinism. Albinos are unable to synthesize any pigments; often with other genetic anomalies. Luecistic birds simply have inordinately, sometimes totally white feathers. Talons, skin, even some feathers, are not affected; have normal coloration.)

I think you may be confusing what is (in many male snowy owls) a normal age-related change in plumage pattern with a genetic hiccup like leucistism. Although snowy owl plumage changes are more complex than many birders realize, in general males are more lightly marked than females, and adults of both sexes average more lightly marked than juveniles. (There’s plenty of variation, though, and researchers like Gary Bortolotti, Marten Stoffel and SNOWstorm team member Jean-François Therrien have shown that some snowies become more heavily marked with age, or go back and forth over the years.) Adult male snowies frequently develop completely or almost completely white plumage, losing virtually all black markings, like the adult male in that photo of Tom. Some researchers have speculated that male snowies may not be able to successfully hold territories and attract a mate until they achieve a largely all-white plumage.