With a toss, Chippewa — a snowy owl tagged on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan — goes back in the air. (©Nova Mackentley)

As as we mark both our third anniversary and the start of our new field season, we’re taking a look back at what Project SNOWstorm has accomplished — all of it with your help, since everything we do is underwritten entirely by donations from the public. Our successes are your successes.

Today, we turn our attention to some of the discoveries we’ve made, and how we’re sharing them with the public and with conservation professionals.

Significant findings: So what have we found? Here’s a small sample of what the data have shown us:

An analysis of thousands of photographs contributed by SNOWstorm supporters created a picture of age and sex class distribution of snowy owls during major irruptions, across an enormous geographic area. (©Alan Richard)

–In very basic terms, we’ve confirmed (based on thousands of photographs supplied by the public) that in the Northeast and Great Lakes, up to 90 percent of the owls that make up major irruptions are juveniles, and that gender and age classes have different distributions on the wintering grounds. This reinforces findings that go back to some early work in the 1980s, but covering a dramatically wider geographic scope and sample size. And as we’ll discuss in more detail tomorrow, these birds are not the starving refugees of common belief, but are generally fat and healthy migrants.

–We’ve documented the degree to which snowy owls use a wide variety of habitats. Based on tracking data, tagged owls used grassland or agricultural habitat about a third of the time during 2013-14, and a little more than half the time the following winter. (The amount of Great Lakes ice has a lot to do with year-to-year changes.) Our tagging also confirmed the degree to which snowy owls use freshwater and marine environments for foraging and roosting, as well as their frequent affinity for urbanized landscapes.

–Our results have shown the extent to which snowy owls, which are small mammal specialists during the breeding season, become highly generalist predators during the winter, often feeding heavily on waterbirds, findings first suggested many years ago through pioneering work by people like SNOWstorm co-founder Norman Smith.

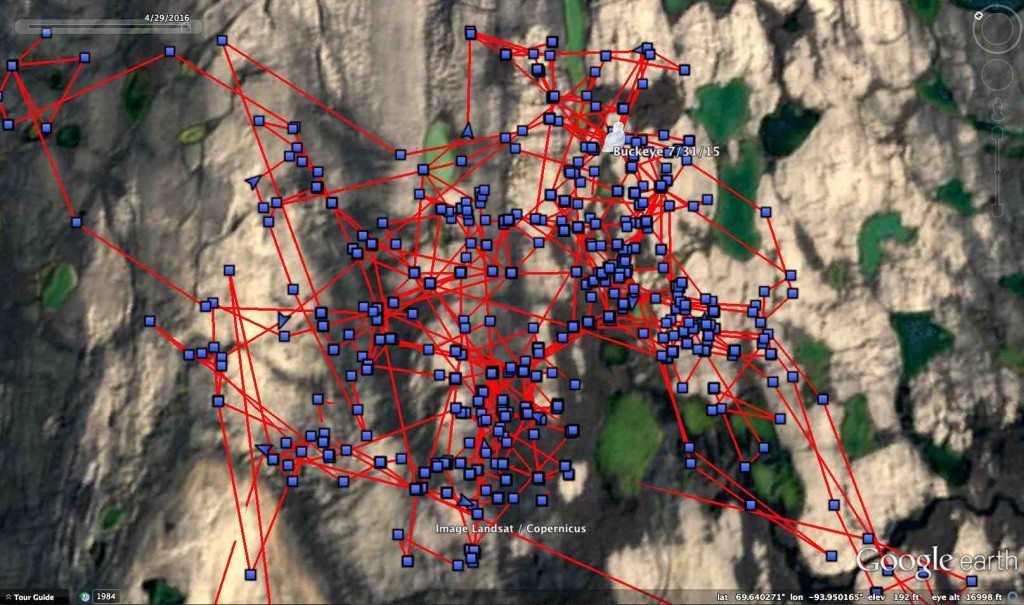

The movements of one tagged female snowy owl, Buckeye, during July 2015. SNOWstorm’s GPS transmitters are providing unprecedented detail into the movements of non-breeding snowy owls. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

–We documented the extent to which snowy owls use ice, both off the Atlantic coast and to a much greater extent on the Great Lakes, in winter and during migration. The owls are presumably feeding on waterfowl using transient open water created by shifting winds. This is especially revealing in concert with satellite-tag data from our colleagues at Laval University in Quebec, which shows that some adult snowies winter on Arctic sea ice and feed on waterfowl that use permanent openings (polynyas) in the ice.

–Although our major focus is winter ecology, we have tracked nonbreeding snowy owls during migration north, and summer in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, a period in the life history of this bird still shrouded in enough mystery that we don’t even know at what age snowy owls begin to breed.

Our flight speed and altitude data represent the only significant such data set for any species of owl, anywhere, and Dr. Tricia Miller from West Virginia University is heading up a team analyzing it for publication. Among other things, this information may prove critical for avoiding conflicts between owls and industrial wind farms, which are rising in greater and greater numbers around the Great Lakes and on their migration routes. (For example Amherst Island, where four of our tagged owls wintered last year, is slated to get 26 turbines, and neighboring Wolfe Island already has 86 turbines.)

The summering movements of non-breeding snowy owls, especially immature birds, are very poorly known. We’ve found that some individuals move over tremendous distances; one male covered 2,076 miles (3,341 km) in an area of 1,347 square miles (3,488 km2); another male used 1,784 square miles (4,621 km2) over the course of several months. By contrast, one young female used just a third of a square mile (0.81 km2) all summer — but before you think this is a gender difference, the summer territory of another tagged female encompassed 1,033 square miles (2,676 km2).

Scott Weidensaul discusses the history of Project SNOWstorm at the 50th annual meeting of the Raptor Research Foundation in October 2016 (©David LaPuma)

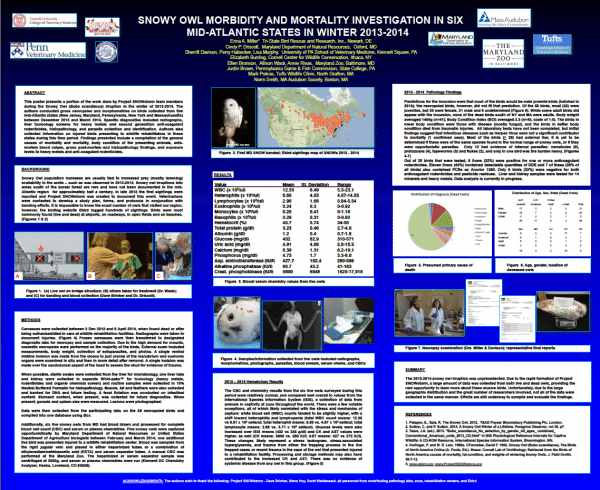

One of many presentations and posters given at scientific conferences based on Project SNOWstorm data.

At the professional level: We’re sharing Project SNOWstorm’s results with the wider scientific community through professional presentations, including organizing a major snowy owl symposium at the 50th international Raptor Research Foundation meeting in New Jersey last October. SNOWstorm members have also made presentations at conferences of the Wildlife Society, the Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, the National Wildlife Rehabilitators’ Association, the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, the Association of Zoo Veterinary Technicians, among others. We will again be participating in the International Snowy Owl Working Group, which will hold its next meeting in March in Boston.

Most importantly, we are also publishing our results in peer-reviewed journals, including several articles currently in preparation or press dealing with age and sex class distribution of snowy owls during the 2013-14 irruption, snowy owl winter habitat associations, migratory flight behavior, and other aspects of snowy owl winter and migration ecology.

Finally, SNOWstorm collaborators have conducted countless public programs, in the field and otherwise, for thousands of people across the U.S. to explain our work — and to share the excitement and privilege we feel being able to work closely with these remarkable birds.

* * * *

Tomorrow, we’ll talk about the work our team of veterinary specialists have been doing to better understand the health of wintering snowy owls, and the environmental contaminants the birds face down here — and how we’re working with airports to make them safer places for owls and people alike. In the meantime, if you’d like to help Project SNOWstorm, it’s easy and tax-deductible — and your gift will be put to very good use.

(Speaking of which, today SNOWstorm is being featured by Indiegogo/Generosity as one of its top fundraisers, thanks to the incredibly strong start everyone’s given us. Thank you so much.)