From left, Drs. Sherrill Davison, Erica Miller and Cindy Driscoll, about to go to work at the PADLS facility in southeastern Pennsylvania. (University of Pennsylvania)

Transmitters get the glory, but there is a less glamorous but equally important part of Project SNOWstorm — the work done by our veterinary team members since the snowy owl irruption in the winter of 2013-14, when SNOWstorm was founded.

Since then, the veterinary team has conducted necropsies (post-mortem exams) and collected physical data on more than 300 owls salvaged in 12 states, the District of Columbia, and three Canadian provinces. Relatively few snowy owls had been examined this way prior to SNOWstorm’s founding, so these exams have provided valuable baseline data concerning the owls’ health and physical parameters.

Some of the birds are examined by collaborators at wildlife diagnostic labs near to where the animals were found dead, but more than half have been examined by our core veterinary team: Dr. Cindy Driscoll of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources; Dr. Sherrill Davison of the Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Lab System (PADLS) at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine; and Dr. Erica Miller, the field operations manager for the Wildlife Futures Program and an adjunct associate professor at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine who spent 25 years in wildlife rehabilitation. Although there are expenses associated with laboratory analyses, the trio volunteer their time to Project SNOWstorm.

This radiograph of a snowy owl shows fractures of the caudal spine and left femur. (©Project SNOWstorm)

The owls are usually found dead by biologists, or found dead, sick or injured by the public and taken to wildlife rehabilitators. Those that are found dead, or are humanely euthanized due to their injuries or poor prognosis, as well as those that do not survive to release, are frozen and shipped to PADLS. The first step, however, occurs at Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research, Inc. in nearby Newark, Delaware. Tri-State has been supportive of Project SNOWstorm since its inception, and provides storage space in their walk-in freezer, and use of their digital X-ray equipment so that each bird can be radiographed before the necropsy. The radiographs enable us to check for fractures, evidence of gunshots, or other organ changes such as thickening of the air sacs that occurs with fungal respiratory infections.

By swabbing the choana — the opening at the rear of the nasal cavity — the veterinarians collect a sample to test for avian influenza. (University of Pennsylvania)

At PADLS, the necropsy begins with a thorough examination and measurements of the outside of the bird, including standard photos of the wing and tail feathers to confirm age and sex by their pattern and feather replacement sequence. The team collects the same measurements that the biologists in the field collect on the live birds they handle: culmen (upper beak) length, bill depth, wing cord, tail length, tarsal width (the tarsometatarsus is the lower leg bone — analogous to the rear foot bone in a human) and the length of foot spread. They look over the birds for signs of injuries, electrocution, predator wounds, eye injuries, and other external abnormalities, including parasites.

Nearly 70 percent of the owls the team have examined have chewing lice, which feed on feathers; generally, those that do not have lice came to us from wildlife rehabilitators and most likely had the lice removed while in their care. The lice are collected in ethanol and taken to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where our collaborators from Drexel examine and identify them. The lice identified thus far are all of the genus Strigiphilus, with the exception of one owl who also had lice from the genus Kurodaia. (Why lice? Dr. Jason Weckstein, the curator of ornithology at the Academy, studies the genetics of bird lice to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the birds that carry them.)

Finally, we collect oral and cloacal swabs, which are used to screen for evidence of avian influenza and Paramyxo viruses, which in birds can causes illnesses like Newcastle disease.

The rest of the necropsy consists of a thorough internal exam of the bird, during which each organ is removed and dissected to evaluate it for abnormalities. This is a little tricky with the snowy owls because we perform a “cosmetic necropsy,”meaning that we make only one abdominal incision and avoid cutting any bones so that the remains of the birds can then be used in taxidermy mounts or museum collections.

As each organ is examined, lesions are described and photographed, and sections are collected for histopathology (microscopic examination), toxicology testing, and bacteriology, and screening for avian influenza and West Nile virus. The toxicology screen looks for heavy metals, organic chemicals like pesticides, PCBs, and other substances, and anti-coagulant rodenticides — rat poisons. Any internal parasites found are collected for further identification; and stomach contents are examined, identified, and collected if needed for additional toxicology.

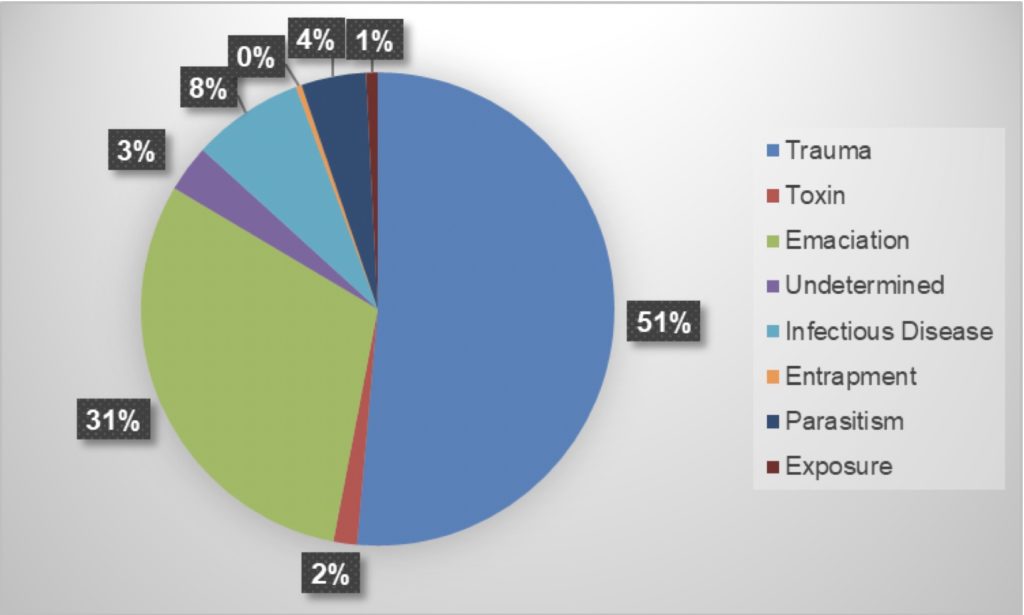

The primary causes of death in snowy owls, as revealed by necropsy findings. (©Project SNOWstorm)

During the first winter of 2013-14, with the heaviest snowy owl irruption in more than 90 years, the majority of mortalities were associated with trauma (largely vehicular impact—usually airplanes or automobiles). Most of those birds were in good body condition when they met their demise. During the subsequent winters, many of the owls we examined were in a thin to emaciated body condition, and many had secondary fungal, bacterial, or parasitic infections.

Data so far show that while more than 40 percent of the owls had exposure to rodenticides, heavy metals, and/or organochlorines, levels were not high enough to be a significant contributor to their deaths; however, the toxins may have made the birds more susceptible to other infections. As we continue to examine owls over the coming years, we hope to be able to better understand the cause and effects of these trends. Our team has published a number of scientific journal articles on these subjects, which are available on our Publications page.

Dr. Ellen Bronson (©Maryland Zoo)

It’s important to remember that the owls that come to rehabbers, or are found dead, may not represent the wintering population as a whole. Data from healthy, wild-trapped owls provide an additional layer of evidence about owl health — and that connects with yet another aspect of SNOWstorm’s veterinary work. Dr. Ellen Bronson at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore heads up research into blood samples taken from live snowy owls, both wild-trapped birds caught for banding and tagging, or those brought to rehabilitators. Live blood samples allow Dr. Bronson and her colleagues to look into still other facets of snowy owl health. (You can read more about this project in a 2020 blog post here.)

If you’re a licensed wildlife rehabilitator, rehabilitation veterinarian or an agency biologist and would be interested in contributing samples or salvaged owls, you can reach Dr. Erica Miller at erica@jfrink.com, or Dr. Cindy Driscoll at cindy.driscoll@maryland.gov.

6 Comments on “Snowy Owl Winter Mortality Investigations”

Wonderful work by extraordinary women! Thank you Drs. Davison, Miller and Driscoll!

Love the owl shirts on everyone!!

It’s good to see these people whose names I’ve known and respected for so many years. Thank you for your work, and this illuminating diagram of the things that bring these great owls down.

It’s good to see these people whose names I’ve known and respected for so many years. Thank you for your work, and this illuminating diagram of the things that bring these great owls down.

This is not a duplicate comment, WordPress.

What a great photo! It’s like the owl is looking at the shirt trying to find cousin Dave.

Erica, that snowy is bigger than you are ! Thanks for what you do. Love to all !’