Lauren Gilpatrick of the Biodiversity Research Institute with Brunswick, Project SNOWstorm’s first Maine owl. (©Scott Weidensaul)

Last year was a heart-breaker in Maine. SNOWstorm had two enthusiastic partners in the Pine Tree State — the Biodiversity Research Institute, and the federal APHIS Wildlife Services staff, which was kept busy the past two years trapping and relocating snowies at Maine’s airports.

BRI generously underwrote a GPS transmitter — and in the weird, frustrating way these things sometimes happen, almost the moment CTT shipped them the transmitter, John Wood and the Wildlife Services crew suddenly couldn’t catch an owl for love or money.

They tried hard through February and early March, knowing that time was ticking down. We’d collectively decided that March 15 would be the cut-off; after that, there was too much chance a newly tagged owl would simply bug out for the Arctic, and leave us with little winter movement data for the significant investment.

I was leading a birding trip in Nebraska on St. Patrick’s Day when BRI biologist Lauren Gilpatrick called to say they finally had a bird — two days after our self-imposed deadline. What to do? With more than a little reluctance, we all decided to stick with the plan, and let the owl go untagged.

Scott Weidensaul keeps a firm grip on Brunswick, which fell for the old Tribble-in-a-trap trick. (©Chris DeSorbo)

This winter, Maine became an even bigger priority for us. In recent weeks, up to half a dozen snowies have been seen at the old naval air station in Brunswick — now an executive airport — so on Monday that’s where eight of us from BRI, APHIS and me (the lone SNOWstorm rep) gathered.

Heavy rain the day before had washed away the last snow, and it was a simple task to find four snowies near the airfield’s secondary runway, mostly tucked up against low barriers across the old taxiways. I was in one truck with John Wood and Adam Vashon from Wildlife Services, and Chris DeSorbo from BRI, while Lauren was in a second vehicle with BRI and APHIS colleagues.

We dropped a bownet within about 50 yards of one of the owls, which was hunkered down so that only the top of its head was visible, but what caught the snowy’s attention almost immediately was a second trap the crew had placed on the taxiway. It a style known as a bal-chatri — a round wire cage with a hamster inside, and nooses made of heavy monofilament. This one was made for red-tailed hawk-sized raptors, and I was a little dubious; the nooses were much smaller than I’d normally use for a snowy, which has huge, densely feathered feet.

And when I say “hamster,” don’t think of the typical brown, short-haired sort — this critter was pure white, with a luxurious pelt that would put an Angora cat to shame. It looked like a Tribble from an old Star Trek episode, or an animated mop head.

Harnessing Brunswicks at the BRI offices — from left rear, Chris Persico, Rick Gray, Weidensaul, Chris DeSorbo and Lauren Gilpatrick. (©BRI Photo)

The owl, however, thought it was riveting. Soon the bird was craning its neck over the barrier, bobbing and weaving with greater and greater intensity — and shortly thereafter, it launched on a gliding attack, grabbed the small cage, and was neatly noosed by one toe.

The cage and its weight were light enough for the bird to drag, but too heavy for it to fly off — a safe balance that prevents toe or leg injuries. We piled out of the truck and raced to the trap, and were soon admiring a gorgeous and healthy adult female snowy.

With a couple of voles to hold her overnight, we gathered at the BRI office in Portland the next morning to band, process and tag the owl, which we nicknamed “Brunswick.” After some initial fussing, she quickly settled down and was (for a snowy owl) typically quiet and laid-back. In addition to taking all the standard measurements, we plucked a couple of small body feathers for mercury analysis — BRI is well-known for its work on mercury contamination in wildlife, and is partnering with us in a big way to analyze samples from the snowy owls we band, tag and salvage, to learn more about this pernicious environmental toxin. (We also took feather samples for DNA work, and to look at the stable chemical isotopes they contain, which can tell us a lot about where the owl came from in the Arctic and what it eats.)

Ready to go to Rachel Carson NWR! From left, front, John Wood, Chris Perisco, Lauren Gilpatrick, Chris DeSorbo; back, Rick Gray, Adam Vashon, Matt Ewing, Scott Weidensaul. (©Scott Weidensaul)

Instead of the second-generation tag we were planning to use last year, Brunswick got one of CTT’s new 3G transmitters, which have been showing much greater energy efficiency, along with some gee-whiz features like onboard temperature sensors and an accelerometer to track even small movements.

Soon Brunswick was ready to go — heading to southern Maine, and her release at the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge near Wells. As I was about to board my flight home from Portland that evening, with snow falling heavily in the dusk, her transmitter checked in for the first time, showing that she was hanging out in the refuge’s extensive tidal marshes.

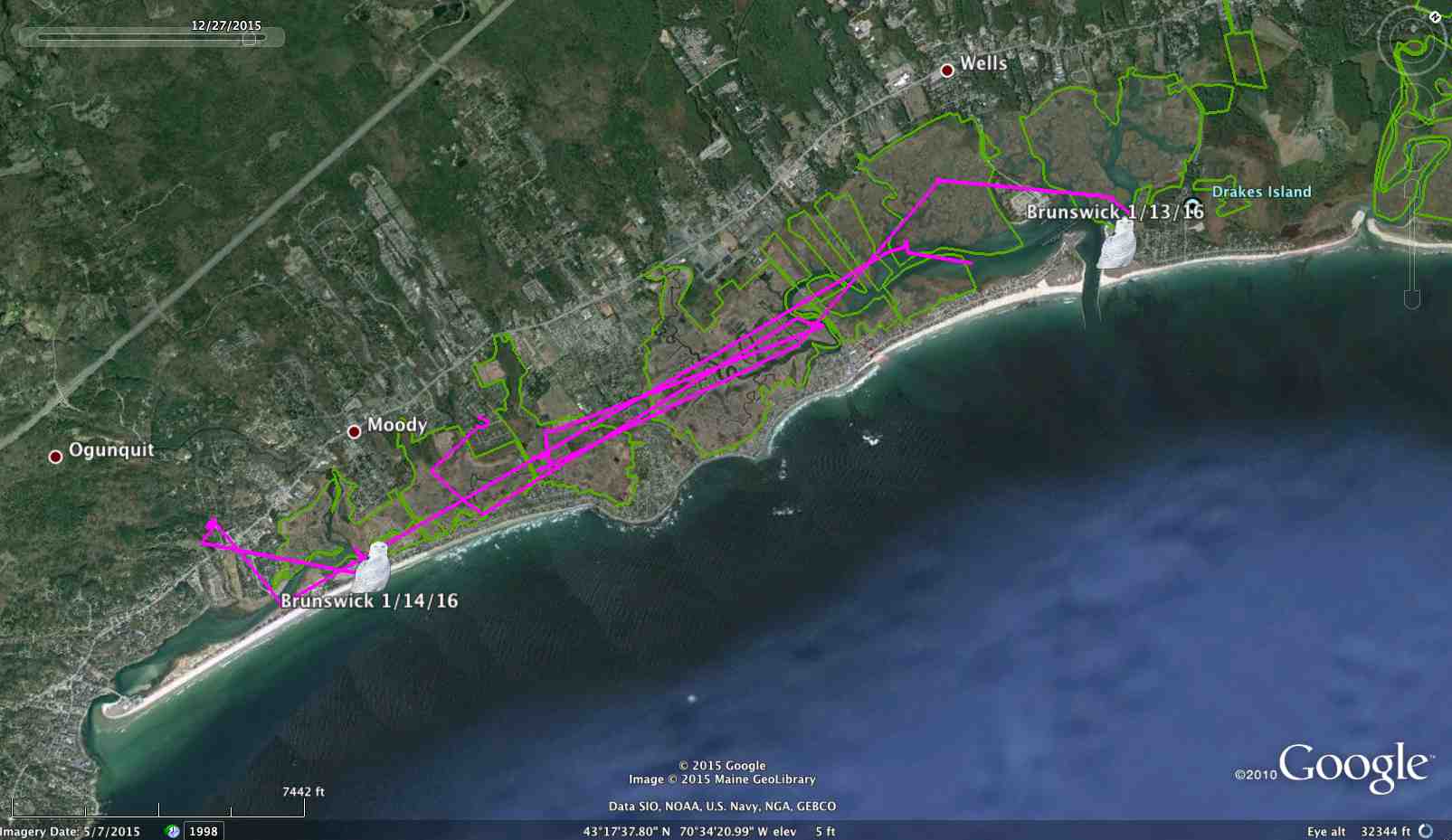

Since her release, Brunswick has been staying almost completely within the bounds of Rachel Carson NWR. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Since then, Brunswick’s been staying mostly within the refuge’s holdings around Wells Harbor, between Ogunquit, Wells and Drake’s Island. (The refuge extends almost 50 miles along the southern and mid-Maine coast, in 14 districts.) She’s made a few forays inland and roosted a few times on beach-house roofs, as she gets to know the area.

Our hope, of course, is that she’ll stay in a nice, safe place like Rachel Carson NWR, and not return to Brunswick or one of the other coastal airports in Maine. One of the reasons we’re partnering with BRI and APHIS in Maine is to learn more about the behavior of snowies that are relocated away from airports, to learn how best to do it so they stay moved — and safe. We’re especially grateful to the refuge staff for their enthusiastic cooperation.

We have some very cool news about some of our other tagged owls — but that can wait for the next update!