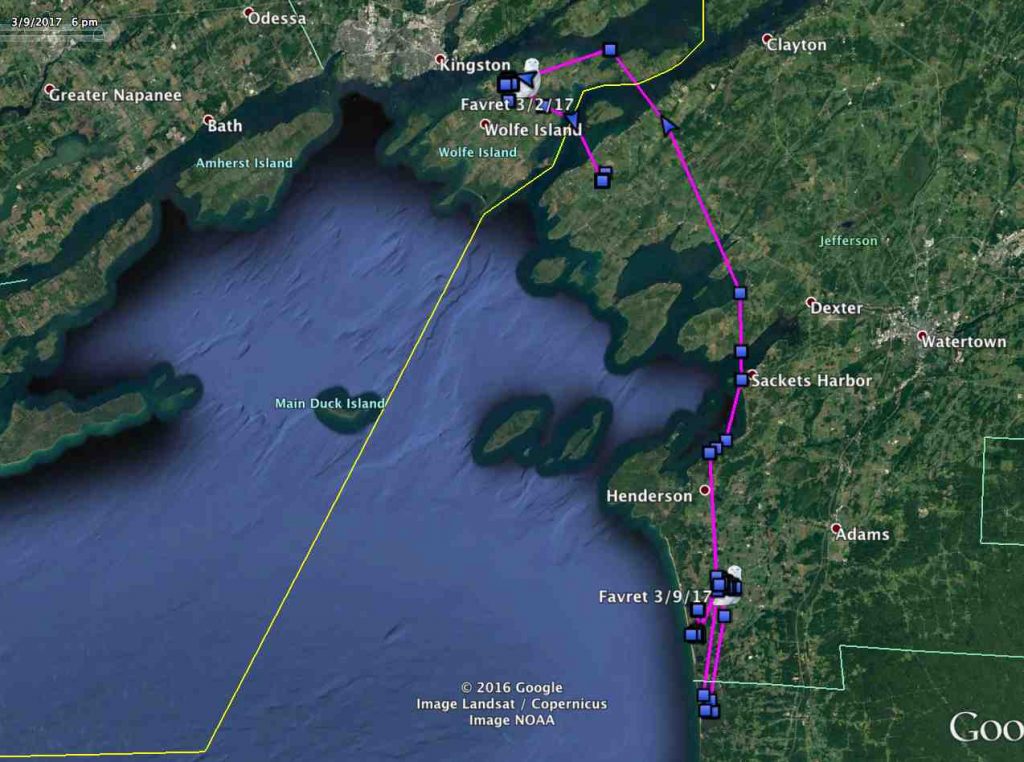

After a short excursion north into Ontario, Favret turned south again, moving along the eastern edge of Lake Ontario to a spot that attracts snowy owls almost every winter. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The past 10 days has been an interesting period, with some unexpected movements, some owls sticking close to their usual haunts, and a couple of absent snowies that may indicate that spring migration is really getting underway (or could just be low batteries).

Favret, the adult female tagged in upstate New York by Tom McDonald, had initially moved north to Wolfe Island on the Ontario side of easternmost Lake Ontario at the end of February. But at the beginning of the month she started moving south again, back across Cape Vincent where she was tagged, down to Sackett’s Harbor, NY, by March 3, and down to North Sandy Pond near the village of Sandy Creek, NY by March 5, a trip of about 40 miles (65 km).

Then she backtracked a bit, and has been hanging out near the town of Belleville, in high, windswept farmland along Sandy Creek (the famous steelhead-fishing stream, not the village — hope that’s not confusing). Tom knows that area well, and as we discussed Favret’s location, he told me stories of previous trapping expeditions there, including a day that involved everything from snowy owls and a red-shouldered hawk to a merlin and a gyrfalcon. It’s the highest, most open ground for miles around — ideal for a snowy.

To the north of Favret, Hardscrabble has since December remained tightly wedded to his winter territory near Cobden, ON. While his flights haven’t been dramatic, the data we’ve collected from him is exactly what we started SNOWstorm to gather — highly detailed information about habitat use and movements in wintering snowy owls.

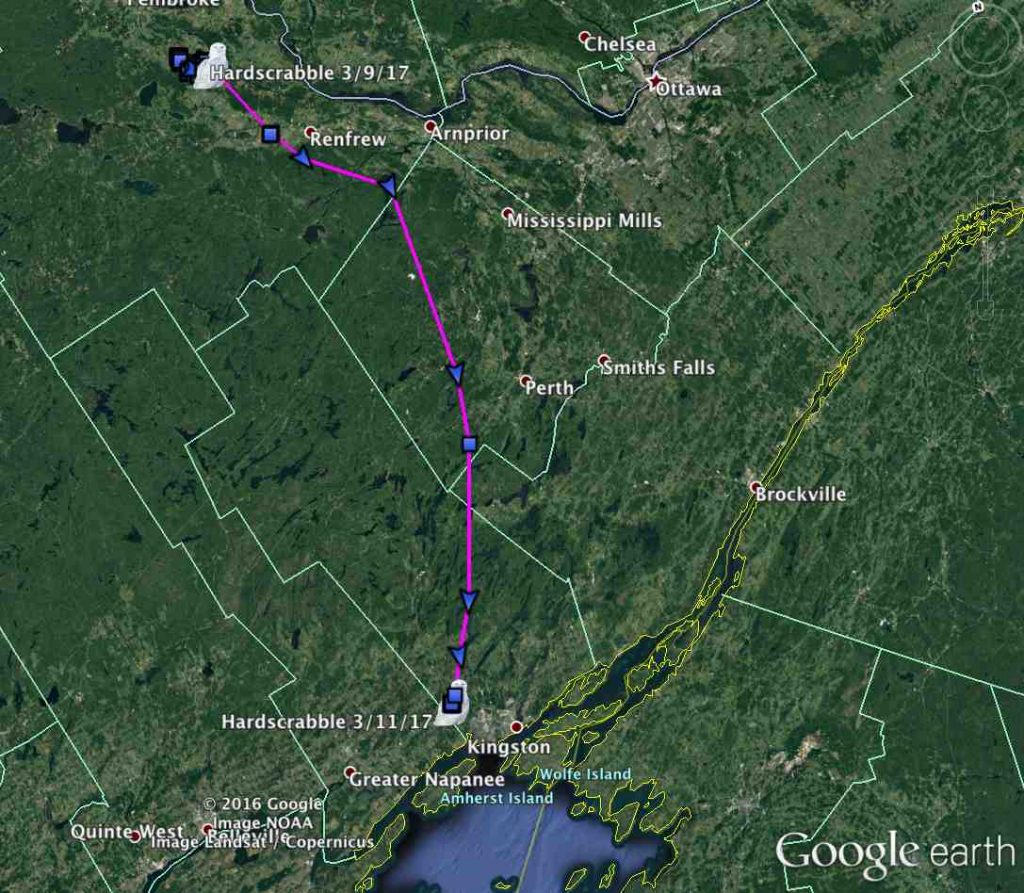

Hardscrabble’s southern skedaddle, from his fairly small winter territory near Cobden, ON, almost to Lake Ontario. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

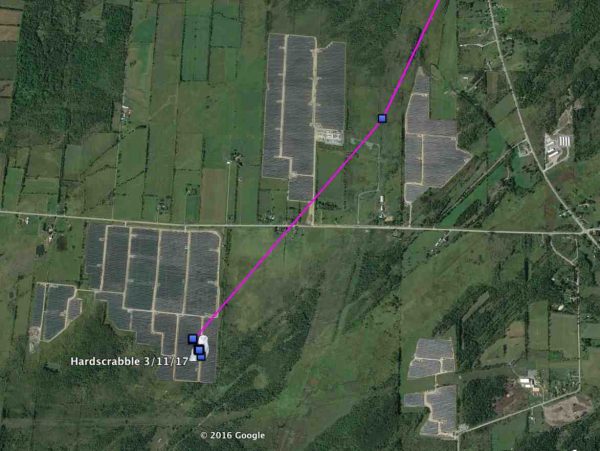

A solar-powered owl in more ways than one, Hardscrabble March 11 in one of several large solar arrays near Kingston, ON. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

But then, quite unexpectedly, Hardscrabble made a 154 km (95-mile) flight almost due south March 10-11, leaving the Ottawa River valley and flying almost all the way to Lake Ontario. At midday on March 11, he was sitting in the midst of an enormous solar panel array just northwest of Kingston, ON, and only about a dozen kilometers north of Amherst Island, where he and many other snowies have lingered in the past.

What happened, and is there is link between two tagged owls moving south in roughly the same period, so late in the season? It’s hard to say. The weather seems not to have been a factor; Favret moved south following a sharply colder, snowier period, when the area east and south of Lake Ontario was getting a lot of lake-effect snow, but there were no dramatic changes in weather (or snow cover, which can hide prey) up in Hardscrabble’s area at the time of his move. It’s possible he was bumped out by a larger, more dominant owl, or he may just be feeling restless as the days get longer and migration season approaches. We’ve seen late-season wandering in the past with other owls.

Baltimore has been playing a frustrating game of hide-and-seek west of Ottawa. We’ve made several more attempts to try to retrap him to retrieve his dead transmitter, thus far without success. He was last seen March 8, just before the fourth and (barring some dramatic development) final attempt to catch him, this one by our Canadian colleague David Okines of the Prince Edward Point Bird Observatory. In all, we’ve invested hundreds of hours in trying to recover his transmitter, and wish it had been more fruitful.

Wells, who had last checked in from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec March 2, was a no-show last week. Her last transmission showed her moving to the northeast, though, and if she continued migrating north, she may already have been beyond the cell network in that part of Quebec — or at least, not in immediate cell range when her transmitter tried to connect Thursday evening. We’ll have to see if we’ve lost her for the season.

We also failed to hear from Dakota out in Saskatchewan, which is one of the very few times she’s failed to check in all winter. But her unit voltage was depleted when we did the big data flush a couple weeks ago, and with cloudy, stormy weather in the Plains recently, she may not have had enough juice. It’s possible she headed north — the limit of cell coverage isn’t that far to the north of her winter territory — but our money is on a low battery, which some sunny weather should correct.

Oswego was also a no-show, and almost certainly that’s been because her voltage was low — the nearly constant clouds and lake-effect snow along Lake Ontario have been a real issue this winter, even with the much more efficient solar panels and batteries on this new generation of transmitter. The lake has remained almost completely ice-free this winter, so northerly winds draw up surface moisture and create perpetual clouds and snow along the downwind shores.

The initial movements of Chickatawbut, which Norman Smith tagged last week in Massachusetts, were detailed in our last update — we’re interested to see this week if she continued inland through New Hampshire as she’d been doing, or looped back to the coast.

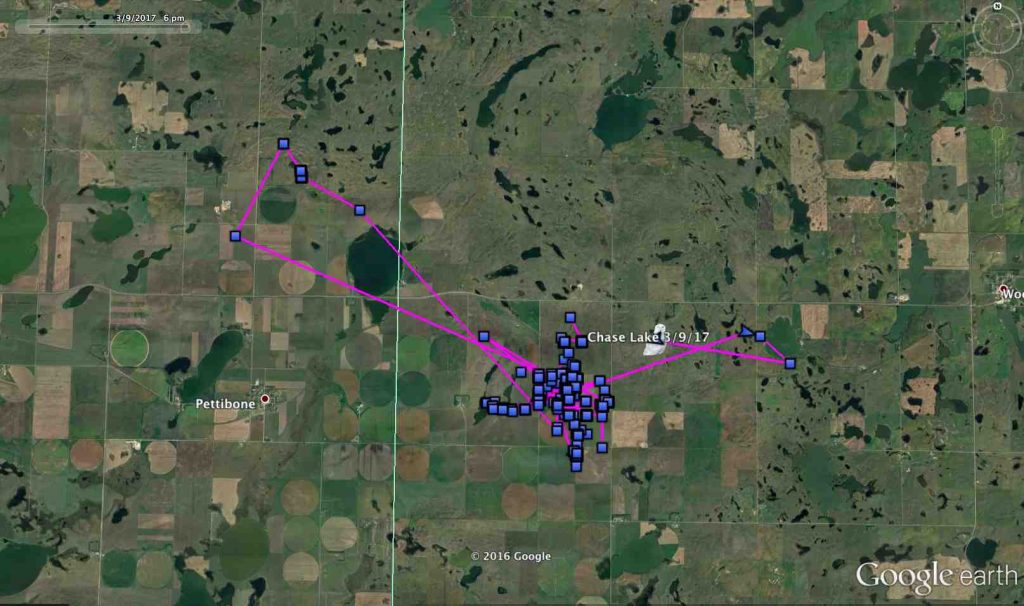

Chase Lake has been hunting the “dead-ice moraine” region of North Dakota, where glacial history set the stage for wildlife-rich habitat. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Chase Lake, our newest North Dakota owl, was ranging a bit farther afield this past week, moving between Stutsman and Kidder counties west of Woodworth, ND. This is classic prairie pothole country, part of the famous “duck factory” of the northern Plains, with millions of small, glacially sculpted lakes, ponds and wetlands — fertile hunting for a raptor, whether hungry for birds or mammals.

This part of North Dakota is known to geologists as a “dead-ice moraine,” formed as glaciers were stagnating and melting at the end of the last ice age — there’s a great explanation by retired North Dakota state geologist John Bluemle here, which makes clear why this is such a pothole-rich part of the prairies, and thus such an important area for wildlife.