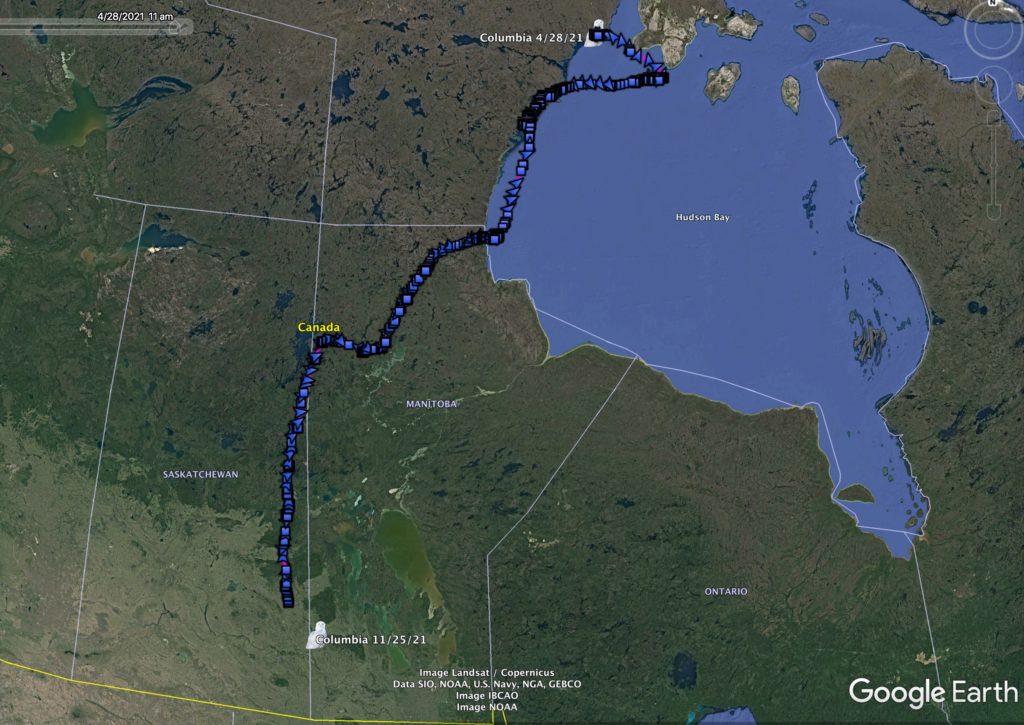

Columbia’s northbound movements from last April (the extent to which her sun-starved transmitter uploaded data in the first batch) and her current location in Manitoba. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Snowy owls have been making headlines this past week, as more and more have been appearing in the upper Midwest, around the Great Lakes, throughout the St. Lawrence River valley and down the Northeast coast to Long Island. One showed up last week on the roof of a school in Goochland, Virginia, just west of Richmond, where snowies are extremely unusual, and another near Winfield, Missouri, just northwest of St. Louis. Sightings have been a little more sparse in the northern Plains south of the Canadian border, but a fair number are back in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

From our perspective, though, the big new was the reappearance of two more tagged owls — especially one that returned after an absence of 18 months, bringing almost 23,000 GPS points and a fascinating story.

Ready to go — Columbia with Gene Jacobs at Goose Pond when she was banded and given a transmitter in 2020. (©Monica Hall)

We’ll leave that bird for the moment, and start with Columbia. She’s an adult female captured in January 2020 near Madison Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary in Arlington, WI, with support from Madison Audubon and trapped and tagged by longtime SNOWstorm collaborator Gene Jacobs. Last year she came south again and spent most of the winter in northwestern Iowa before heading north in April.

On Nov. 25 — a lovely Thanksgiving gift — she checked in from southwestern Manitoba, just a few kilometers from Asessippi Provincial Park on the Saskatchewan border. Her battery voltage was low, as is often the case with birds that have just come down from Arctic, and we only got a partial upload of her stored data, which took her through the end of April as she was moving up the west coast of Hudson Bay opposite Southampton Island. We expect that as her battery voltage recovers we’ll get additional uploads and find out where she spent the summer.

Fond du Lac, getting ready for her transmitter. (©Rich Armstrong)

The other alumnus back in touch with us is Fond du Lac, by coincidence another Wisconsin bird trapped and tagged by Gene, a fourth-year female caught in February 2020, along with two other snowies, near Waupun, WI. We named her Fond du Lac in honor of Fond du Lac Audubon, an anonymous donor to which had underwritten the cost of the transmitter. She wintered near her capture area, and migrated north in early April 2020.

And then — nothing. She didn’t reappear last winter, and we never know whether that means a mortality, a transmitter failure or a bird that simply stayed too far north for cell coverage, since our transmitters work through the GSM cell network. In this case, it was the last, as we found out Nov. 21 when Fond du Lac checked in from near the Cree community of Eastmain, QC, near the southeastern edge of James Bay.

As you can see if you explore her map, after she left Wisconsin FDL (as we often shorthand her name here) migrated northeast across James and Hudson bays — a bit of a surprise, since a lot of our western Great Lakes owls often go up the west side of Hudson Bay into the central Arctic. She followed the ice on Hudson Strait southwest around the Ungava Peninsula another 550 km (340 miles), then moved inland and nested about 60 km northwest of the Kangirsuk, an Inuit village on the north shore of the Payne River.

Fond du Lac’s movements from April 2020 until this month, when she was on southern James Bay. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Come the winter of 2020-21, instead of migrating south, FDL headed north, where her solar-powered transmitter — robbed of sunlight by the long subarctic winter nights — went dormant at the beginning of January. A month later it came back online, and recorded how FDL spent February, March and early April ice-riding along the south shore of Baffin Island. Then she moved quickly inland and nested again, remaining on Baffin until she started south in early November.

Will she continue south to more settled (and cellularly reliable) areas? She’s already at the northern edge of the boreal forest, which isn’t a welcoming habitat for a tundra owl, so I don’t expect she’ll want to hang around there, but she’s obviously surprised us already. And if she does keep moving south, it will be fascinating to see if she swings southwest back toward Wisconsin, or keeps on a more easterly track that would bring her to southern Ontario or Michigan. Many of our tagged adult owls are strongly faithful to their wintering sites, but obviously not so far with FDL.

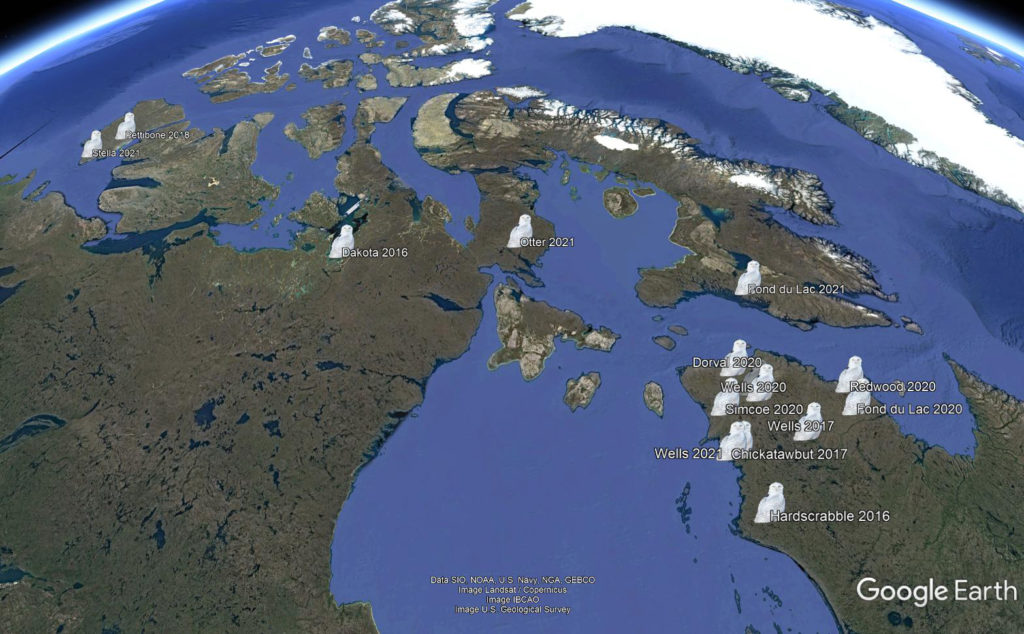

All 15 nesting locations we’ve recorded so far for SNOWstorm-tagged owls. (At this scale, Yul’s 2020 location in the Ungava is obscured by Wells 2020, so you’ll only count 14.) Many other birds summered in the north but did not breed, either because they were still too young, or likely because prey populations were too low. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Realizing that Columbia may very well also have nested last summer, Fond du Lac’s nest brings to 15 the number of tagged owls we’ve been able to document breeding in the Arctic and subarctic since 2016. When we started SNOWstorm it was with the specific goal of studying winter movement ecology, so this exceptionally rich dataset on summertime movements and nesting is the cherry — or should I say, 15 cherries — on the sundae.

Early though it is, this is shaping up to be a very exciting winter. We don’t expect Columbia and Fond du Lac will be the last returning owls, and we’ll be starting new tagging operations in several areas in the coming weeks. Stay tuned!

3 Comments on “Two More Returnees!”

Yay! The short light deprived days of winter are always aglow with snowy updates in our in-boxes.

I’m certain I can say for many, we truly enjoy the efforts of all involved in this volunteer basis ( utmost fascinating) endeavor. Thank you!

I am thrilled to see so many snowy owls checking in this year. It was a once in a lifetime experience to see Columbia outfitted with her transmitter and to know she is still here to share her data. Keep up your amazing work and thank you so much for all of the new updates.

Monica Hall

Thanks for your insightful narrative(s) of the incredible flight travels these tagged Snowies undertake during fall and spring migration, and how they spend their time in the north and south!