Marshfield, an immature female snowy owl, tagged March 6 near the Wisconsin town of the same name (©Gene Jacobs)

At the start of Project SNOWstorm, we set an incredibly ambitious goal — to tag at least 20 snowy owls with GPS/GSM transmitters this winter. With the addition of two more owls in the past few days, we’re almost there.

On March 6, Gene Jacobs tagged an immature female near Marshfield, Wisconsin, about 40 miles northwest of our nearest snowy owl, Buena Vista. “Marshfield” is our 18th tagged owl and the fourth snowy tagged in Wisconsin this winter — in addition to Buena Vista we also have Freedom, north of Appleton, and Kewaunee, just a few miles from Lake Michigan.

On Saturday, March 8, Tom McDonald tagged an immature male in Odgensburg, New York, right on the St. Lawrence River. Tom named the bird “Oswegatchie,” for a the nearby river that originates in the Adirondacks. The name is pronounced “ah swee got chee,” and comes from the Onondaga word for “black timber.” Oswegatchie is well known in Ogdensburg, Tom said, and has been hanging out lately near the local high school.

We’ll have maps for these birds in a few days — as with all our owls, we’re delaying release of movement data by at least three days.

And along those lines, we continue to withhold the map data for Womelsdorf, the Pennsylvania owl we tagged last week. Someone — we’re not sure who — had a bal-chatri trap in the one of the fields the owl uses the day after he was banded and tagged. Because this owl had not been reported on the state bird list or eBird — and because he’s proven to be extremely localized in his movements — we’re withholding the location for the time being.

We’ll have a batch of updated maps from the March 9 transmission on Wednesday, but I can give you a sneak peek at some of the highlights. As I mentioned in a comment yesterday, we were pleased (and a little relieved) to hear from Hungerford, a young female originally tagged on at Assateague Island, which had flown north to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in late February — then dropped off the map. We were starting to worry she might have met with an accident.

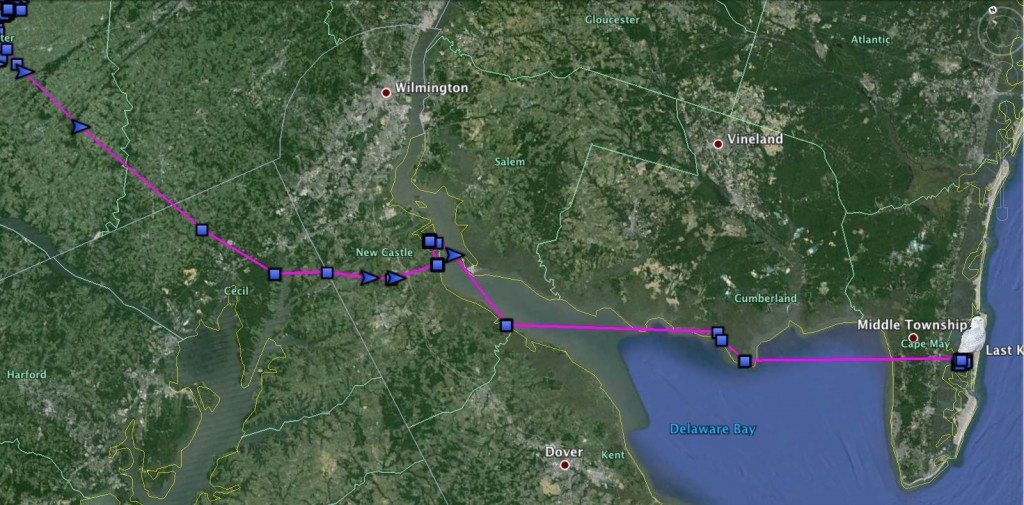

Hungerford’s latest trek from southeastern Pennsylvania to the coast of New Jersey (©Project SNOWstorm)

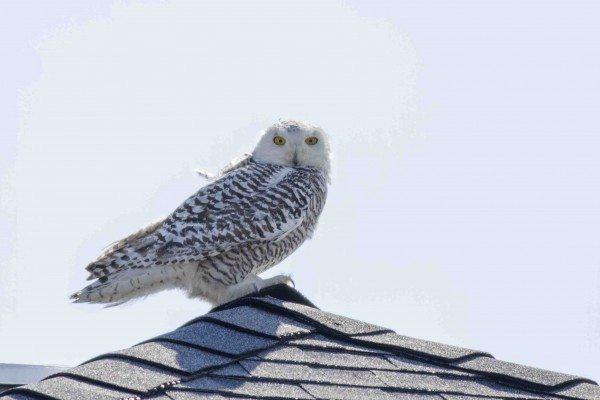

Sunday evening she checked in, though — and she’s been on the move in a big way. She’d flown back south into the Delmarva, cut across Delaware Bay and southern New Jersey, and was near Stone Harbor when the transmission came through. This morning, we asked some colleagues in that area to check her out for us, and they got some great photos of Hungerford looking hale and fit.

Hungerford, “down the shore,” as they say in the mid-Atlantic, on a rooftop near Stone Harbor, NJ (©Sam Gallick)

One of the terrific features of these GPS transmitters is that we receive 3D data — not just latitude and longitude, but altitude as well. When Hungerford left Lancaster County, for example, she made a long, straight flight into northern Maryland, averaging about 1,000 feet above sea level, quite different from the low-level, local flights she made in the days preceding it.

It will be fascinating to see what kind of altitude the owls achieve when actively migrating north, especially if they cross open water for any distance. So far as we know, this will be the first time anyone’s been able to determine the migratory flight altitude of any species of owl, anywhere.

A few other highlights from the upcoming map updates: Braddock, who has been hanging fairly close to the Braddock Bay area near Rochester, NY, all winter, went on a bit of a ramble last week, traveling west past the Niagara River into Ontario and then looping back. He continues to spend a lot of time out on the ice edge on Lake Ontario, generally moving offshore at night (presumably to hunt), then back to land or inshore ice for the day.

Sandy Neck, in Massachusetts, has shown a real affinity for Martha’s Vineyard, making the trip back and forth from the Cape Cod mainland to the island several times. And Plum, the newest relocated owl trapped at Logan Airport by Norman Smith, has been hanging out around the mouth of the Merrimack River near Newburyport, Mass.

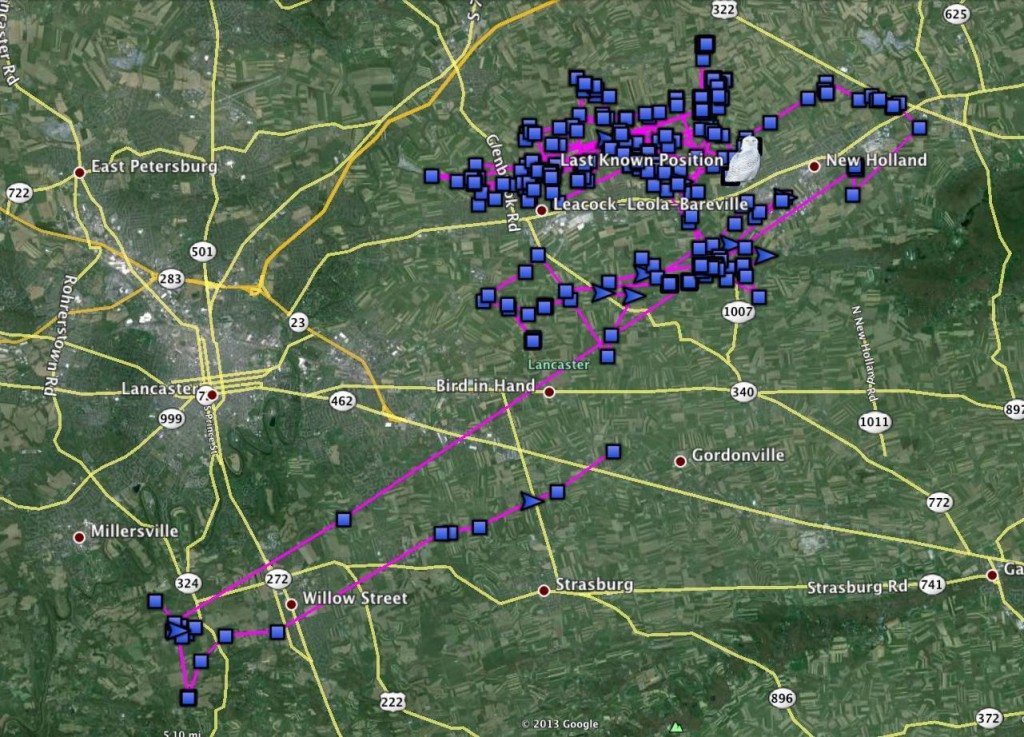

Amishtown remains in Lancaster County, PA, but he’s using a wide-ranging territory that stretches almost 13 miles from east to west, and seven or eight miles from north to south. That’s in stark contrast to Ramsey, who has barely stirred from a one-square-mile patch in his namesake town in Minnesota since he was tagged Jan. 26. Like Womelsdorf, he’s the definition of a home body.

There’s lots more — for instance, where is Erie on his frozen odyssey on the Great Lakes? Check back Wednesday evening for the latest updates to find out.

4 Comments on “Two New Faces”

I love checking out all the beautiful owls and their territories. Keep up the great work! Out here on Block Island, RI we have at least 2, some say 5. Such a thrill to see them hanging out on the island.

Scott,

FYI – wasn’t sure how to enter a comment about Ramsey so am doing it here since this is the latest email I’ve received. This is just an observation you might not know about but maybe you do. Another very good birder I know of showed me a partial skeleton of one of Ramsey’s meals. This incident happened a few weeks ago and I’m sorry I didn’t make time to report it until now. My birder friend said he found Ramsey in some trees in the open area just north of Coburn’s. He said he stayed in his auto when he found Ramsey feeding on a tree branch. He watched until Ramsey was done feeding and then left the tree. When Ramsey few off, something dropped to the ground from the tree branch. After Ramsey left, he said he was curious as to what was Ramsey’s meal, so he trod through the snow and found the carcass as it had dropped to the ground when Ramsey flew off. He showed me the carcass and it was a Ring-necked pheasant hen. All that remained was the hen’s two feet which where still joined to the hip bone. A small part of the spinal column was intact but everything else was stripped clean! The efficient eating skill of these predators is amazing. I am wondering if this owl is capable of taking a feral cat and would it? I know that Great Horns do but am not sure if a Snowy would attempt to. Just curious. Thank you for all the work you do with these owls.

Yet another question and thank you for this answer as well as those prior.

I am curious how the packs accommodate growth and how long it takes an owl to be fully grown?

Thank you,

Robin

Great question. The convenient thing about birds is that they have a single growth spurt while in the nest, and shortly after they fledge they are essentially as big as they’re ever going to be. Unlike mammals, which have a prolonged growth period, or reptiles, amphibians and fish, which grow throughout their lives, birds reach their adult size in a matter of weeks. So while the harnesses include some wiggle room for seasonal weight gain and loss, we don’t have to worry about a bird growing at all once it’s more than a week or two out of the nest (and of course, these owls have been out of the nest for at least six or eight months).