Baltimore finishes off the previous night’s leftovers (the legs of an unlucky rabbit) on Long Beach Island, New Jersey. (©Northside Jim)

As usual, there’s a lot of ground to cover, literally and figuratively, in this week’s update. To make it more manageable, I’m going to focus on the owls in the East in this post — I’ll cover the Midwestern birds in the next one.

The first owl is one of those close-but-no-cigar situations, so to speak. We’ve been working this winter with John Wood at USDA Wildlife Services in Maine, and Lauren Gilpatrick and Chris Desorbo at the Biodiversity Research Institute in Portland, ME, to tag a relocated airport owl in that state.

John had great success earlier in the winter trapping and moving snowy owls — until he received one of our transmitters in February, that is. Then the well dried up. Despite many, many attempts over the next month and a half, using a variety of techniques, John, Lauren and Chris were unable to catch any of the snowies that were at Portland’s Jetport, or other Maine airfields. They had more close calls than they could count, but no captures.

It’s been like that this winter — we’ve all felt a little jinxed because so much as been so hard. “Nothing worth doing is ever easy,” as my SNOWstorm colleague Dave Brinker likes to say — so everything we’ve been doing this winter has been worthwhile. Because none of it’s been easy.

In the case of Maine, we’d all agreed that March 15 was the logical cutoff for tagging new owl. Project SNOWstorm’s primary goal is to study the winter movement ecology of snowy owls, and while it’s fun (and important) to get migration and summer data, tagging an owl too late in winter makes it likely we’d get minimal data before the bird headed north. And by mid-March we’d expect to see many of the snowies to be heading north.

So what happened? Two days after the deadline, on St. Patrick’s Day, Lauren reached me by cell phone in Nebraska, where I was leading a crane-watching trip, to say that they’d finally caught one of the Maine owls — a bird that had been banded previously at an airport there.

Baltimore basks in some mild spring sunshine on Long Beach Island, which was a hotspot in New Jersey for snowy owls this winter. (©Northside Jim)

It was a painful decision, but after discussing it she and the rest of the Maine crew, along with Dave and I, decided to stick with the original plan. The owl was moved to a safe location away from the airport, but released without a transmitter.

Fortunately, Lauren, John and Chris remain enthusiastic about this partnership — and that transmitter they have will keep just fine over the summer, and be ready next winter as soon as the first snowy comes south to Maine.

New Jersey is another state where we had buzzard’s luck this winter. We had transmitter sponsorships from the Cape May Bird Observatory and two generous anonymous donors, but try as we might, we were unable to trap and tag even one owl in the Garden State.

But we wound up with two “unofficial” New Jersey owls anyway. One of them is Baltimore, who was back on the boards last week. He must have been tucked in a cellular dead zone the previous week when he missed checking in, but last Thursday evening he was on Dinner Point in Little Egg Harbor, New Jersey, the general area he’s been using since late February.

One photographer, who has been keeping an eye on the owls of nearby Holgate NWR this winter, sent us some great photos of Baltimore on the beach at Holgate, mantling the remains of a cottontail he’d snagged for dinner.

This owl’s been restless, moving up and down Long Beach Island and the adjacent bay as much as 13 miles (20 km). (That’s not surprising — after he was relocated from a state airport in Baltimore to Assateague Island in mid-February, he quickly flew more than 150 miles northeast to the New Jersey coast.)

While Baltimore sometimes rests on beach houses at Ship Bottom or Beach Haven, or the empty sand of Holgate, he also flies across the three-mile (4.6 km) bay to roost in the salt marshes on the mainland, which like Holgate are part of Forsythe NWR.

The other New Jersey owl, Monocacy, remained missing in action last week. We’re not sure what’s happening with her, but suspect her transmitter just isn’t getting enough sun to fully charge up in order to phone home. Longer days may help; this isn’t the first owl to have this happen.

Up north, Braddock is still in the St. Lawrence Valley just south of Montreal, where he’s been sending backlogged data from earlier this month, when his unit dipped below the minimum voltage for cell transmission. (Unless the voltage drops very low, the transmitter still records and stores the GPS locations every half-hour.)

No real changes in status for Orleans in upstate New York, or Millcreek in suburban Toronto — both are hanging out just where they’ve been all winter. Instead, the big news this week was Geneseo, who has made the first long-distance flight of the spring migration.

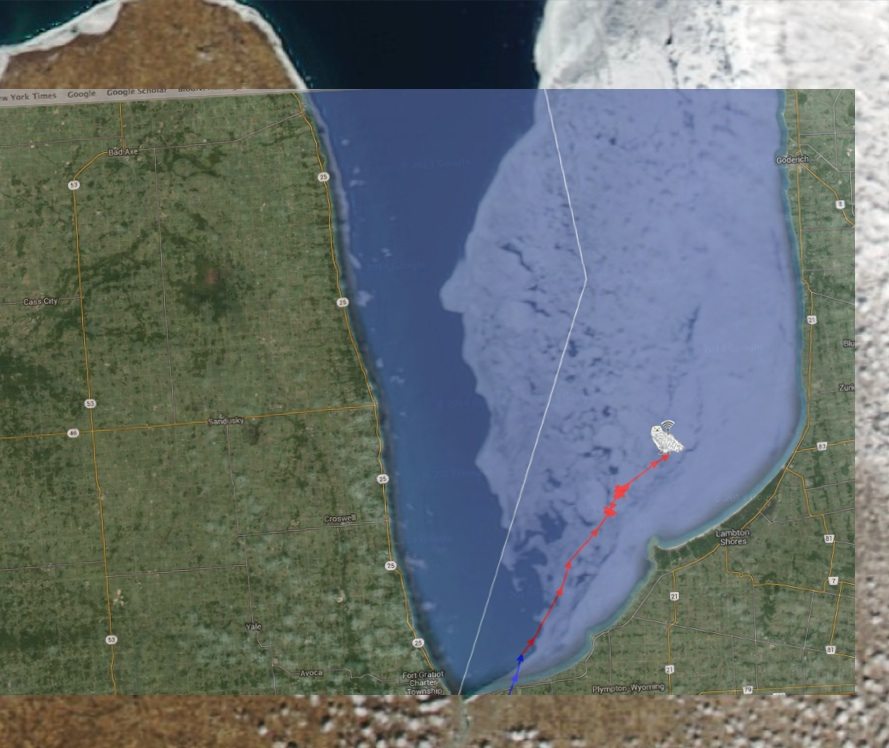

An overlay of Geneseo’s track on March 19, and the satellite image of ice on Lake Huron, shows how this male owl skirted the open water for the lingering ice shield along the eastern side of the lake. (©Project SNOWstorm, Google Earth and NOAA CoastWatch)

The evening of March 9, Geneseo was still on his winter territory south of Rochester, New York. There was about a three-day gap in his data, which we can’t really explain (its voltage was fine), but when the unit began collecting GPS locations again the evening of March 12, Geneseo had moved 164 miles (264 km) almost due west, and was on the ice along the north shore of Lake Erie, near Port Stanley.

For the next six days he remained out on the ice, then made a quick, predawn flight March 19 across the neck of southwestern Ontario to Lake Huron, where he was back on the ice that evening when he checked in, having skirted the edge of the melting ice shield. This is the same area that Erie had been using a few weeks earlier.

That’s it for the eastern cadre that checked in on Thursday — next time, we’ll cover the Midwestern crew of owls. Stay tuned!

11 Comments on “Updates from the East”

Thanks for the updates. I look forward to these.

What about the NYS Snowie, Chaumont? No mention of him?

Love all the updates!

Chaumont last checked in on 2/11/15, so may be out on the lake ice out of cell service. We’ll let you know when there is an update!

It is possible that one of the owls hanging around Lake Huron was seen the other day floating down the river and then being harassed and dived at by two peregrine falcons I posted video someone had taken on the Lambton Wildlife facebook page.

Hoping there will be a Snowy Owl tracked in Maine, if not this winter, then next. Thanks for the hard work of Project SNOWstorm and its partners in Maine, the Biodiversity Research Institute and USDA’s Wildlife Services, in helping us to better understand these raptors of the Arctic. Here’s our latest blog post on the efforts in Maine: http://acadiaonmymind.com/2015/03/no-gps-tracked-snowy-owl-fly-over-acadia-national-park/

On March 19, 2015, we saw a snowy owl on the Bayonne Golf Course, a favorite place of Monocacy’s. We’ll keep looking. Hopefully the transmitter will come back on again.

Any info on which Snowy has been hanging around Salisbury Beach in MA? It has a transmitter; appears to be a male since it’s almost all white. There are a number of us who would like to know its name and be able to track it as it migrates north. Thanks!

lakeladyinNH If it’s one of ours, it must be a malfunctioning transmitter, because none of the owls we’re tracking is in Massachusetts. It’s also possible that it’s a bird that was tagged with a satellite transmitter by another research team, like Laval University in Quebec, which has been tagging snowy owls on Bylot Island in the Canadian Arctic for a number of years. SNOWstorm collaborator Norman Smith at Mass Audubon has also done his own satellite tagging for years, but I’m not sure if Norman deployed any this winter — he was so consumed with trying to keep up with snow removal at the Blue Hills Reserve that he wasn’t able to deploy any of our GPS/GSM transmitters.

lakeladyinNH Does he look like Cranberry?

shilfiell lakeladyinNH I contacted Norm Smith with Mass Audubon and the Snowy Owl Project. He put a transmitter on this owl March 14th and released it on Plum Island which is right across the way from Salisbury State Reservation. Here’s a couple photos of him: