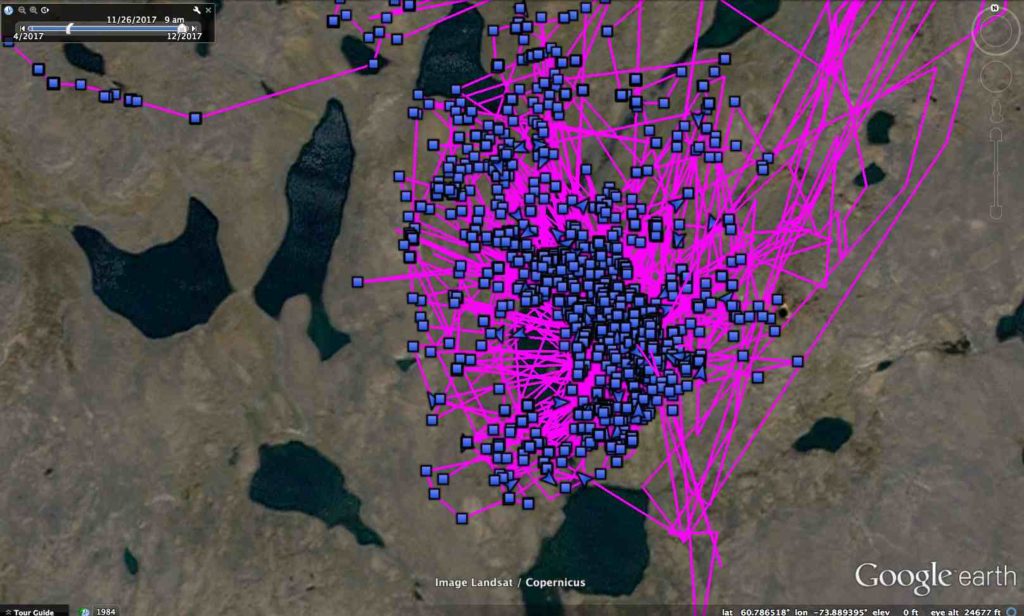

Wells’ spring and summer movements, from late April to the end of October, including her nest site in northern Quebec. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

As we mentioned last week, two of our 2016-17 owls have come back south and checked in. Chickatawbut has been quiet since her initial check, likely because her battery is still recharging. But Wells checked in a few days ago and uploaded her entire previous eight months’ worth of data, all in one enormous batch — the first time we’ve gotten an owl’s whole summer backlog in one big rush.

In all, the data trove totaled more than 10,500 GPS locations, tracking her movements in superb detail from southern Quebec last April, up through the middle of Quebec in May and into the Ungava Peninsula. Once there, she quickly settled down, and the data make very clear that she nested — part of the huge concentration of snowy owls that were breeding in the Ungava this past summer, and whose offspring make up the bulk of this winter’s heavy irruption.

We’re still looking carefully at Wells’ data, but here’s a synopsis of a very eventful year for this adult female.

She’d last connected the end of April, when Wells was near Lac Saint-Jean, about 200 km (125 miles) north of Quebec City. April 22 she began moving steadily north through the boreal forest and muskeg of central Quebec. Even though her flight bouts were typically brief — an hour or two, then a rest, which is normal for migrating snowies — over the next week she made good time, only stopping for extended periods a couple of times, usually on islands in the immense hydroelectric impoundments that have reshaped the eastern drainage of James Bay.

By May 1 Wells had moved roughly 1,000 km (600 miles) almost due north, and a few days later she had moved across the Mélezes and Feuilles rivers and into the heart of the Ungava. This vast area of subarctic tundra and rushing rivers is framed by Hudson Bay to the west, Hudson Strait to the north, and Ungava Bay to the east.

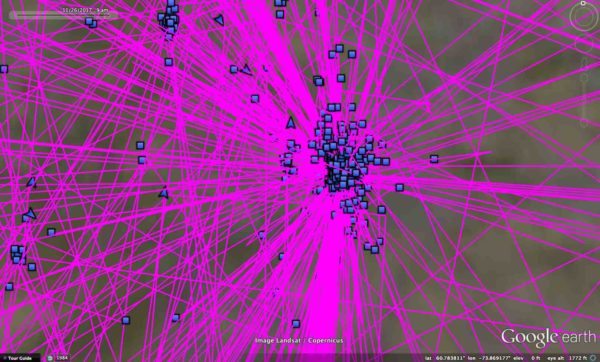

The general area of Wells’ nest, covering about 1,000 hectares (2,700 acres). Most of her movements in this area are later in the summer, after the chicks have achieved some independence. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Wells made a final push, then settled down May 17 on the headwaters of the Vachon River — and here is where she apparently nested. For the next four months, she rarely moved outside an area of roughly 1,000 hectares (2,700 acres), at the core of which was as 5 hectare (12 acre) nest site, where she spent the vast majority of her time. We have thousands of data points in this tiny area, showing how rarely she strayed from her nest, eggs and later her chicks.

Home base — the few acres around the nest site. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Along with similar nesting data we collected last summer from Dakota, up in Arctic Nunavut, this is the most detailed movement record of nesting female snowy owls that we know of, and something we’ll be taking as much closer look at in the months ahead. We can’t know how many chicks she raised, but the fact that she remained in the area all summer suggests she was guarding and helping to provision a successful clutch of babies.

Four months to the day after settling down in her breeding territory, Wells began moving again on Sept. 17, and over the next month and a half she wandered in a big, flattened figure-eight some 400 km (250 miles) across northern Ungava, arriving back just south of her nesting site on Oct. 30. At this point she turned south — right on time, based in tracks from other owls we’ve followed, which often commence their southbound migration around the end of October or early November.

By that time, in that region, daylight is a scarce commodity, with the sun barely clearing the horizon. Wells’ solar-powered transmitter worked well but eventually the juice ran out, and it went into hibernation Nov. 5, when she was still fairly high up in the Ungava. It kicked to life enough to grab a few points as she headed south — on Nov. 20 near the Quebec/Labrador border, and Nov. 22 in western Labrador. Then it woke up enough to send us an initial transmission on Nov. 26, when she was somewhere near the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The huge data transmission again depleted Wells’ battery, but it should be recharging, and when it reconnects next time we’ll start to get current data for her this winter. But in the meantime we’ve put the huge treasure-trove of her spring, summer and autumn movements on her map page — have fun exploring the subarctic landscape in her company!

3 Comments on “Wells’ Excellent Summer Adventure”

I’ve spent a half-century focusing on the Red-tailed Hawk; field studies (from Maine to Alaska, mostly in N Ohio), captive breeding, trapping, banding, rehabbing, educational display (and, as master falconer, hunting with the species). I marvel at these new transmitter data, so precisely characterizing the owls’ movements, seasonal and daily. Would love to have such for my Red-tails. From field studies, I have a rather comprehensive understanding of local, territorial occupations and movements. Would so much wish to have, as here with the snowies, good understandings of post-natal movements of immatures and floaters, un-mated adults. Well done, Snowy Owl students.

John, thanks for the comments. You’re right, among the big unknowns about snowy owls are things like dispersal, post-fledging mortality and overall juvenile survival rates. Those are questions we’d like to tackle, and about which the SNOWstorm community may be hearing more in the future.

Thanks for the update. Wells had babies!! It’s fantastic to be able to follow Wells’ summer movements in such detail.