Does this hurt the owls?

The last thing we want to do is put snowy owls at risk. The capture process is quick and harmless, and backpack harnesses and lightweight transmitters similar to what we’re using have been shown to have no effect on either the survival rate or breeding success of these owls. (see reference 1)

A lot of people worry that snowy owls are forced down here by hunger, and must be slowly starving to death. So this must stress them, right? In fact, researchers have found that most snowy owls (especially during major irruptions) are healthy, with normal weight and fat reserves. If we catch an owl that’s underweight or shows signs of illness, we obviously won’t tag it.

Some of the owls that come south each winter will certainly perish, but most of those will succumb to vehicle collisions (including with planes, since many hang out at airports), rodenticide poisoning, electrocution on power lines and other unnatural hazards. In fact, our project will help us better understand what threatens snowy owls on the wintering grounds, because we’re working with wildlife health specialists to test them for toxins, and to perform necropsies on those that are found dead.

Since these are GPS-GSM transmitters, what happens when the bird is out of cellular coverage?

The transmitters use signals from the orbiting GPS satellite system to regularly collect precise information about the bird’s location, at preset intervals around the clock, then transmits it at regular intervals via the cellular network. When the bird is outside cell range, the transmitters can store up to 100,000 locations – more than 12 years’ worth, at the rate we usually collect data. They continue to transmit until the owls move north of the cell system in southern Canada, and send the stored data months or years later when the owl comes back south into cell range again, providing the most detailed information on their migration and summer movements ever collected.

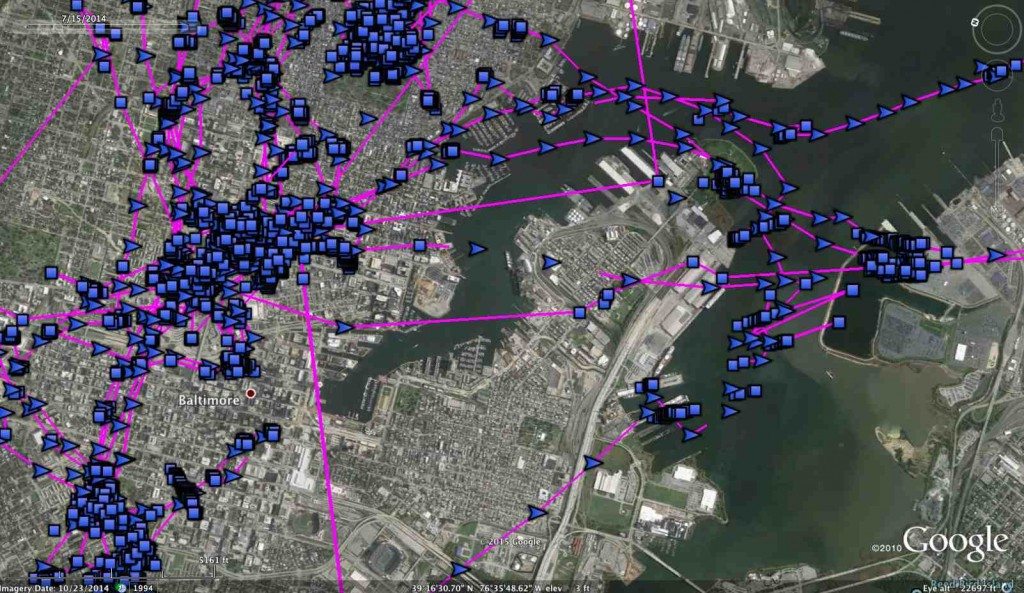

Movement data in Baltimore for “Monacacy,” collected at 30-second intervals. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

What does the “high resolution” data look like?

The degree of accuracy of this data is beyond anything available with older satellite transmitters. When the transmitter is triangulating its position from several GPS satellites, it can provide a location accurate to a fraction of a meter. Viewing the data through Google Earth, we’ve been able to tell (and confirm with ground observers) that an owl was perched on a particular piling in a dock, or the south side (rather than the north side) of the roof of a beachfront house.

You can learn more about the kind of transmitters we use here.

How can this data tell us anything about foraging behavior?

Birders (and many ornithologists) have long assumed that snowy owls are diurnal, since they can be more active than most owls in daytime. But as snowy owl experts have long known, these birds are active primarily at night — and Project SNOWstorm is the first effort to collect extensive and highly detailed telemetry data on their hunting behavior and nocturnal activity ranges.

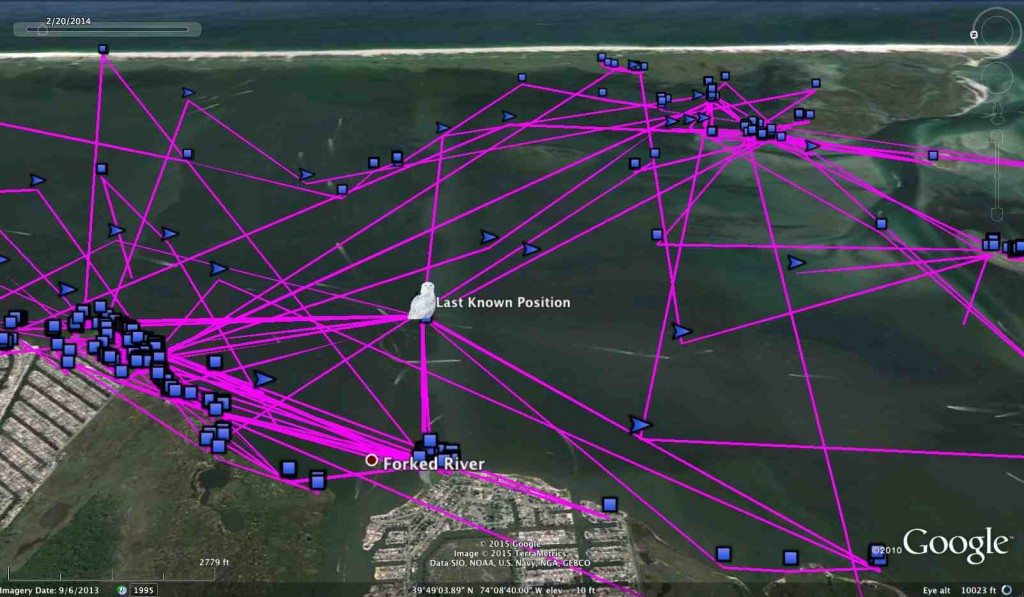

Telemetry data shows how a snowy owl wintering on the New Jersey coast hunts mostly over open water — including using a channel marker in the middle of the bay as a hunting perch. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

One thing we’ve shown is the extent to which some coastal owls hunt offshore, presumably preying on sleeping ducks, grebes, gulls and other waterbirds — we’ve even pinpointed the channel markers and buoys they use as nighttime hunting perches. Similarly, we’ve been able to see how inland birds are using irrigation ditches, roadsides and other habitat for their hunting. Because these transmitters communicate by cell phone, we can reprogram them on the fly – literally – with instructions to increase or decrease the number of fixes we want them to take.

The newest generation of transmitters now includes an accelerometer, which continuously records information about the movement of the tagged bird, even between GPS location fixes, giving us ever an almost seamless look at when and how they are active.

Does Project SNOWstorm’s work translate into real conservation?

Yes — that’s one of our biggest goals.

To protect a species, you have to understand its entire life cycle, and much about the winter ecology and behavior of snowy owls, especially after dark, has been poorly studied. Questions we’re answering include where these irruptive birds are coming from and where they go; how far and how fast they move across the landscape during the winter; what kinds of habitats they’re using, and how that differs from daytime to darkness; and what threats they face while here in the south, including what their fate may be following big irruptions. The transmitters provide the first look at the behavior of individual wintering snowy owls in a way that will shed light on many aspects of their ecology, which will ultimately better inform conservation efforts.

The tracking program is just part of a larger study to look at multiple aspects of their ecology and physiology, however. Since the project’s inception, SNOWstorm’s wildlife veterinarians and pathologists have conducted necropsies on hundreds of snowy owls that were found dead from accidents and other causes, to determine cause of death and the presence of disease or parasites. The birds’ tissues (and those from live owls captured for tagging) are sampled to test for environmental toxins like rodenticides, heavy metals, mercury and pesticides; their DNA is analyzed to decipher the genetic makeup of North America’s snowy owl population; and stable chemical isotopes in feather, blood and tissue are examined, which provide insights into where in the Arctic the birds originated, and how their diets change with time. This is by far the most ambitious effort ever to look at the health and condition of snowy owls, and the toxic threats facing them.

How are these transmitters mounted to the birds, and would they impair their wing movements?

The transmitters are held in place with a kind of backpack harness, made of low-friction Spectra® ribbon, that is a design that’s been used for decades on many birds of prey, including large owls. Similar harnesses have been used with satellite transmitters on snowy owls, with no effect on the owls’ survival or breeding success. They certainly do not restrict their flight – many of the owls we’ve tracked have flown thousands of miles to and from the Arctic over the course of many years.

References

1. Therrien, J-F., G. Gauthier and J. Bêty. 2012. Survival and reproduction of adult snowy owls tracked by satellite. Journal of Wildlife Management 76(8):1562-1567.