With cutting-edge tracking technology, we can follow the movements of snowy owls in astounding detail, and for years at a time. This research has been made possible by the generous contributions of the general public and a variety of ornithological and birding organizations.

Collaborating scientists in Project SNOWstorm are tagging snowy owls with next-generation GPS-GSM transmitters made by Cellular Tracking Technologies of Rio Grande, NJ.

How they work

Its black solar panel gathering sunshine, the small transmitter sits in the middle of a snowy owl’s back (©Northside Jim)

These solar-powered transmitters record locations in three dimensions (latitude, longitude and altitude) at programmable intervals as short as every 30 seconds, providing unmatched detail on the movements of these birds, 24 hours a day.

Unlike conventional transmitters, which report their data via Argos satellites in orbit, GSM transmitters use the cellular phone network. When the bird is out of range of a cell tower, the transmitters can store up to 100,000 locations, then transmit that information — even years later — when the bird flies within cell coverage.

The transmitters weigh about 40 grams — about as much as seven U.S. quarters, and only 1.5-3 percent of the bird’s weight. They are attached with a backpack harness made of low-friction Teflon® ribbon that goes over the bird’s wings. Studies of snowy owls wearing conventional satellite transmitters in this fashion have found no evidence that they increase mortality or decrease breeding success (Therrien et al. 2012).

Still, we’re careful only to tag snowy owls that are in robust health. As experienced researchers, we assess every owl we catch to make sure it is in good shape, with normal weight and healthy fat stores. Any owl that seems questionable will not be tagged.

What have we learned?

A lot, much of it unexpected. Going into this study, little was known about the local and landscape-level movements of snowy owls on the wintering grounds, nor about their nocturnal hunting activity and range size — certainly not at the extraordinary level of detail these transmitters provide.

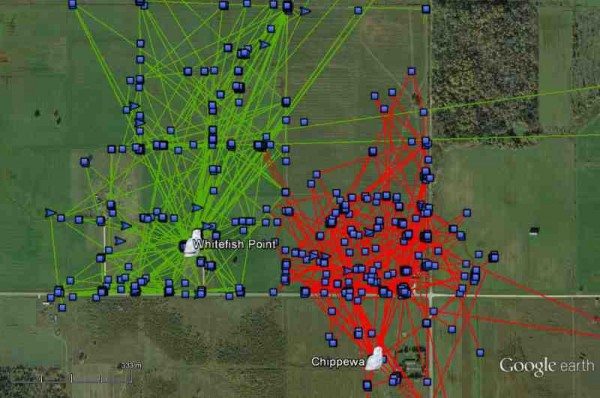

Two adult female snowies, tagged in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, barely moved a quarter-mile from their adjacent territories. (Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We’ve found that some owls are home-bodies, and rarely move a quarter-mile from where they were banded. Others roam across hundreds of miles in a few weeks, moving from Atlantic barrier islands to Amish farm country and back to the coast.

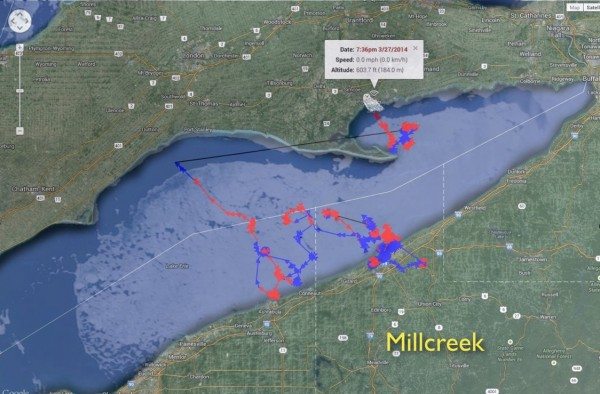

We’ve shown how some snowy owls move out onto the frozen surface of the Great Lakes for weeks or months at a time, apparently hunting for waterfowl using the cracks that open and close endlessly between immense, wind-driven sheets of ice. (In this, they may be practicing a lifestyle some adult snowy owls follow in the Arctic, wintering on polynyas — areas of open water in the pack ice — where they hunt sea ducks.)

Some snowy owls spend weeks or months on the frozen Great Lakes. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth; MODIS ice imagery by NOAA CoastWatch )

We confirmed a long-held suspicion that snowy owls feed heavily on birds in the winter, especially ducks, geese, grebes and gulls — and for the first time have documented in detail their hunting behavior at night over the open ocean, often using channel markers and buoys as hunting perches.

By necropsying snowy owls that are found dead from accidents, disease and other causes, and analyzing tissue samples, we have learned that these great hunters are exposed to a wide range of environmental contaminants, from rodent poisons to mercury to pesticide breakdown products like DDE, which may affect their behavior and reproduction.

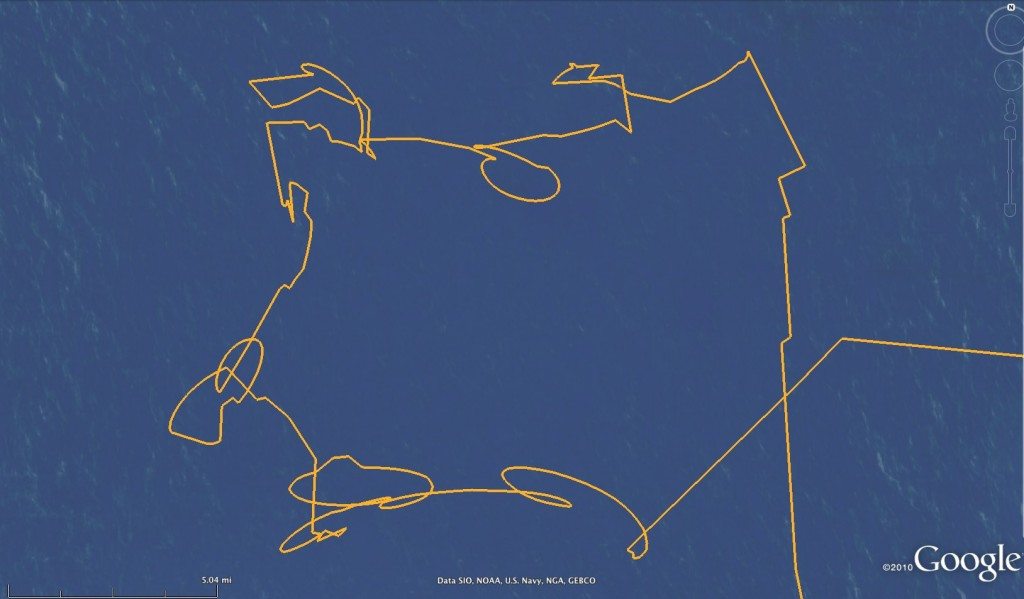

Doodle-like tracks on Hudson Bay show where a snowy owl was riding an iceberg, pushed in great loops by wind and tide. (Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

To the north and back

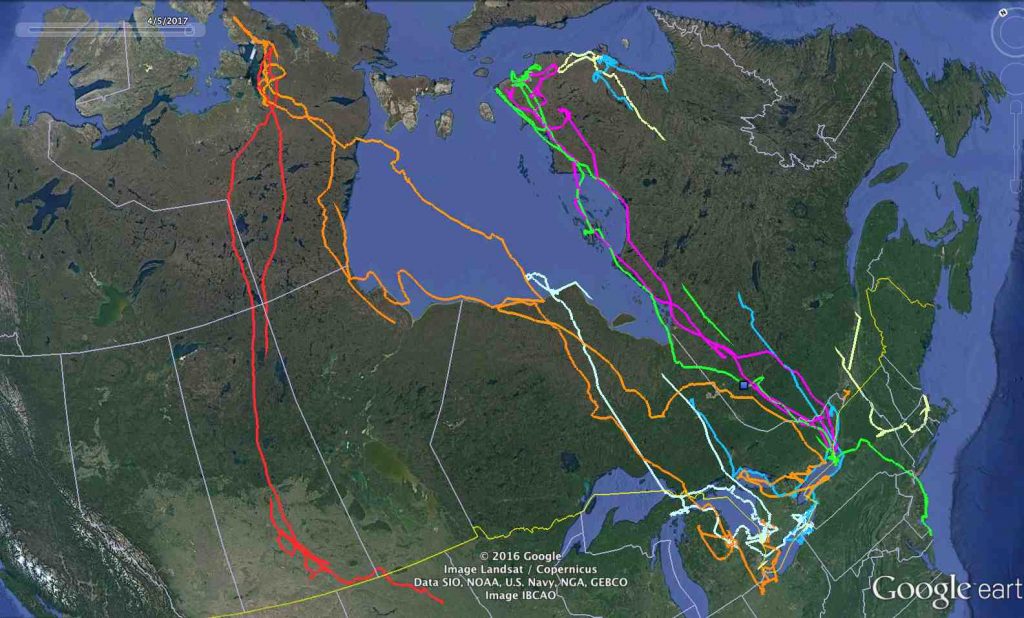

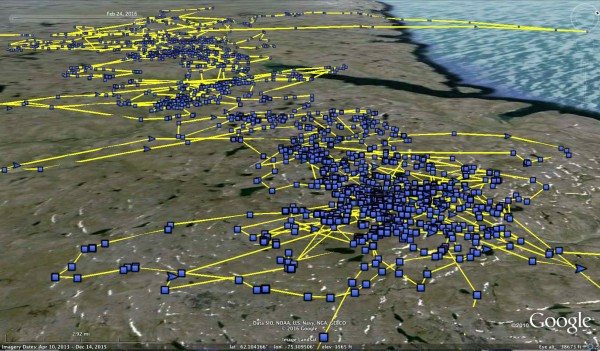

Some of the long-distance movements by SNOWstorm owls returning to the Arctic breeding grounds (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Once the owls migrate north beyond the limit of the Canadian cell phone system, we lose direct contact with them — but their transmitters continue to log precise GPS locations, storing them up until the unit is back in cell range. When the owls migrate south the next winter (or the next, or the one after that) the units transmit their stored information, which represents the most detailed, granular record of the movement of owls in the Arctic and subarctic ever made.

While our major research focus remains on the winter ecology of these birds, getting this highly detailed migration and summering data is like the icing on the cake. Our tagged owls have summered primarily in northern Nunavut and the Ungava Peninsula — sometimes drifting for days on icebergs in James and Hudson bays.

A fresh window in the lives of snowy owls

In the summer of 2015, Baltimore zigzagged more than 2,000 miles along the shores of the Ungava Peninsula. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

No one has ever tracked snowy owls with the level of precision and detail that these new transmitters afford. While our primary interest is the winter movement ecology of snowy owls, the transmitters have also given us an unprecedented look at the movements of these birds on their summer range in the Far North. Because most research on this species has focused on nesting adults, this is especially true of the movements in the Arctic and sub-Arctic by snowy owls not yet old enough to breed.

Just as some sub-adults wander widely in winter, while other remain in small territories, we’ve seen dramatic differences in the summer behavior of non-breeding snowy owls. Some wander across huge areas — one male traveled 2,076 miles (3,341 km) across an area of 1,347 square miles (3,488 sq. km). Another moved 881 miles (1,418 km) across an area of 1,784 square miles (4,621 sq. km.). In contrast, a young female barely budged out of a summer territory of 0.3 square miles (0.81 sq. km).

Our Goal

Thanks to the public’s generosity, since 2013 we have tracked nearly 100 snowy owls in 17 states states and provinces using GPS/GSM transmitters, as well as conduct a range of DNA, chemical isotope, and toxicology studies on hundreds of live owls captured for banding, and salvaged owls that were killed or died while on the wintering grounds.

With your help, we are continuing our work in the field and the lab — tagging additional snowy owls, while continuing to monitor those we tagged previously. The generosity of private donors and bird conservation groups has made this work possible.

Any amount will help, and contributions are tax-deductible through the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art, a 501(c)3 nonprofit. You can donate online here, or by check to:

Project SNOWstorm

Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art

176 Water Company Rd.

Millersburg PA 17061

References

Therrien, J-F., G. Gauthier and J. Bêty. 2012. Survival and reproduction of adult snowy owls tracked by satellite. Journal of Wildlife Management 76(8):1562-1567.