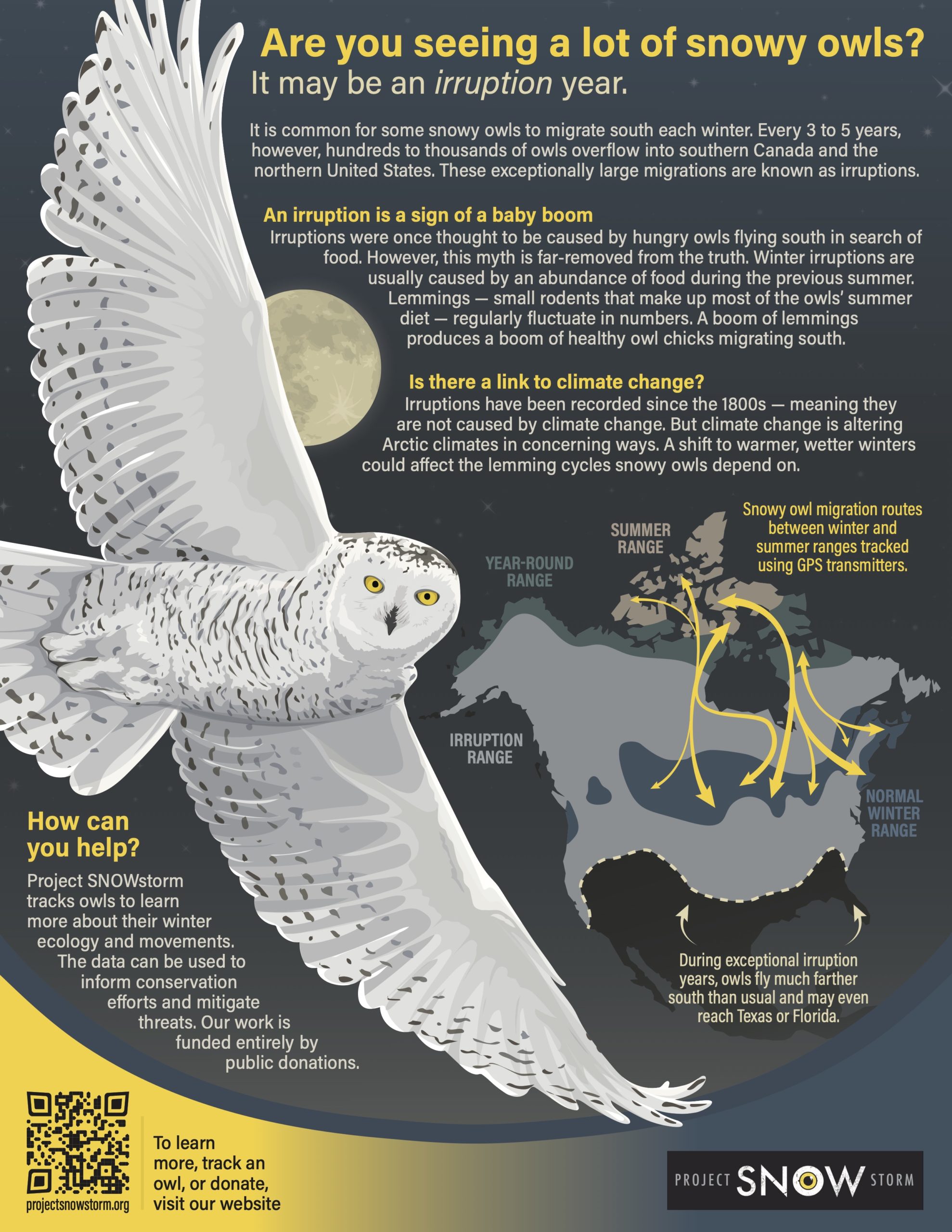

Snowy owls come south in unpredictable invasions known as ‘irruptions.’ It’s mostly about food and babies, but we have a lot to learn about this phenomenon.

Snowy owl migration is complex; some birds migrate south predictably and regularly, while others remain on the breeding grounds or actually move north, onto the Arctic sea ice, hunting in perpetual winter darkness. But every once in a while, for reasons that are not fully understood, snowy owls come flooding down from the north in a phenomenon known as an irruption.

Smaller irruptions happen, on average, every four or five years, but once or twice in a lifetime a mega-irruption occurs, when snowy owls show up much farther south, and in vastly greater numbers, than usual.

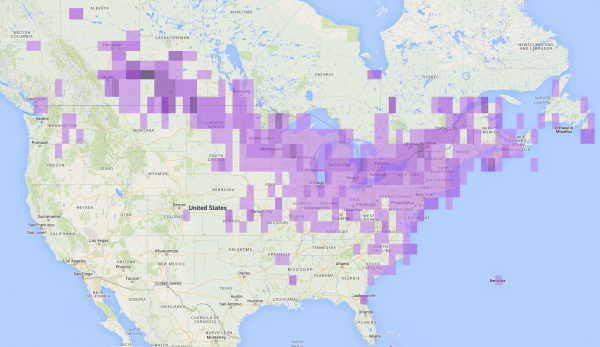

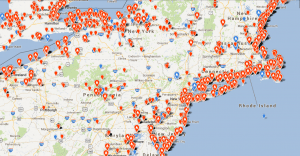

The winter of 2013-14 was one such extraordinary event, the largest irruption in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions perhaps a century. Snowy owls were reported as far south as Florida and Bermuda. In 2014-15, another sizeable irruption occurred in the Great Lakes and East, and farther west than the previous year’s.

- Abundance maps of Snowy Owls reported to eBird in winter 2013-14. (map from eBird.org)

- What a SNOWstorm looks like. This eBird map shows some of the snowy owl sightings for Nov.-Dec. 2013. The irruption zone actually stretched from Minnesota to Newfoundland, with owls as far south as northern Florida. (map from eBird.org)

Irruption myths:

Most people assume that hunger has driven these owls south, and that they are doomed to slowly starve to death in this unfamiliar southern landscape. Both assumptions are generally wrong.

It’s not hunger that usually produces these mega-flights, but an absurd abundance of food during the summer breeding season. High populations of lemmings, voles, ptarmigan and other prey lead to large clutches of owl eggs. There is growing evidence that snowy owls from many parts of the Arctic may congregate to nest in areas where prey is abundant.

Good times in the Arctic. Seventy lemmings and eight voles ring a snowy owl nest in northern Quebec in 2013 – evidence of the abundant prey that made the following winter’s irruption of young owls possible. (© Christine Blais-Soucy)

That happened during the summer of 2013 in northern Quebec, where lemming populations were booming and snowy owls enjoyed a banner nesting season. That autumn, thousands of those young owls moved south.

During the summer of 2014, snowy owls had a banner breeding season on Bylot Island in the Canadian Arctic. That may have been responsible for the unusually large number of irrupting snowy owls that moved in the Northeast and Great Lakes the following winter. Another major breeding event in northern Quebec in the summer of 2017 may have been at least partially responsible for an irruption six months later.

Far from starving, most of these Arctic migrants are perfectly healthy – in fact, our veterinary team’s research has shown that snowy owls in major irruption years tend to be fatter and heavier than those in non-flight years. Only occasionally do food shortages appear to prompt southerly movements of snowy owls (as happens routinely with species like great gray and northern hawk owls). In those cases, many of the irrupting owls are adults, not juveniles.

Not all of the snowy owls that come south in winter will survive, of course – the mortality rate for young raptors of any species is very high. But most will succumb to vehicle collisions, rodenticide poisoning and electrocution on power lines, to name three common causes. Starvation is fairly rare, and often the result of other, underlying causes, although starving birds are more likely to be found and taken to rehabilitators. Because healthy birds don’t usually end up in human care, this can make it seem that most irrupting snowy owls are in trouble. They are not.

Donate today