The results are in from Plum’s necropsy (conducted, as was Sandy Neck’s, by Dr. Mark Pokras at Tufts in Boston), and they confirmed what we suspected — that she almost certainly drowned.

Plum was “in great condition, [a] recently eaten rodent in the gizzard, and bloody foamy fluid in the trachea and lungs,” Dr. Pokras said. It seems all but certain that she was swamped by winds or high waves around daybreak on March 30 as she was trying to cross the mouth of Salem Harbor.

As we noted in the last update, she and Sandy Neck weren’t alone. Four or five other snowy owls (birds without transmitters or bands) also washed up on Massachusetts beaches in the week after the storm.

Plum’s transmitter seems to be none the worse for wear, and after we give it another day or two in the sun to fully recharge, Norman Smith will deploy it on a new owl — there are still quite a few along the Massachusetts coast. Sandy Neck’s, on the other hand, has been much more erratic, and we’re not comfortable using it. That unit will go back to CTT for repair and reconditioning, with an eye toward using it next winter.

We had some fascinating updates from the latest download Tuesday night. After being wedded like a limpet to his namesake town in northern New York, Oswegatchie seems to be on the move. In the early hours of April 2 he flew across the St. Lawrence to an area about nine miles away that he’d visited March 13, then pushed farther north into southern Ontario.

He’s spent four days near the town of Hallville, moving around between farmland and a large quarry. It’s only about 30 miles (48 km) from Oswegatchie, but it’s the first significant movement he’s made all winter.

Speaking of former homebodies, Kewaunee pushed farther north into Green Bay the past three days, remaining off the mouth of the Oconto River in Oconto County, Wisconsin. Unlike the bulk of Lake Michigan, Green Bay is still pretty solidly frozen, but satellite images show some big cracks along the western shore, including one where Kewaunee has been staying.

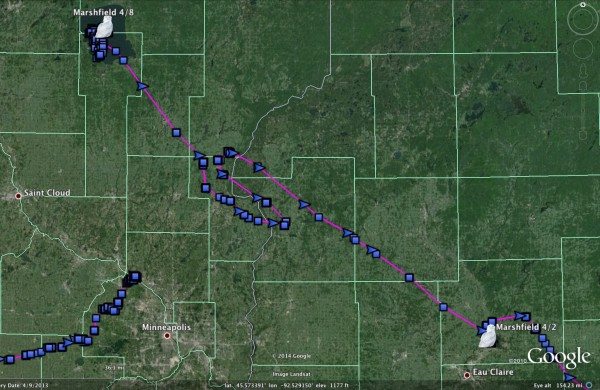

Marshfield made by far the longest flight of this batch — 255 miles (410 km) since leaving Chippewa Falls, WI, on April 2. She did a big S-turn through the St. Croix River valley north of St. Croix, and arrived a little before midnight on April 5 at Mille Lacs Lake in eastern Minnesota. She’s been hanging out on the ice there ever since on this, Minnesota’s second-biggest non-Great Lake.

Marshfieldf’s 255-mile trip to Mille Lacs Lake (that’s a bit of Ramsey’s March track in the lower left.) (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

In the past five days, Erie has moved from the farmland of eastern Michigan onto the ice and shoreline of Lake Huron’s southern tip at the inflow to the St. Clair River. At least, his tracks sure look like he’s been riding around on ice — the latest satellite images show relatively little ice remaining in that part of the lake. But Erie is obviously finding a few floes on which to float.

Both Amishtown and Braddock remain on the north shore of Lake Ontario. Amishtown remains about 30 miles (48 km) east of Toronto, in the same general area he was using three days ago near Whitby, Ontario, roosting on big trucking distribution warehouses near the waterfront. It’s an area Braddock passed through on March 24, but didn’t linger.

Braddock, meanwhile, has spent the past five days on Prince Edward at the eastern end of Lake Ontario — a remarkable peninsula (well, technically now an island, since the Murray Canal cuts across its isthmus). He’s been hanging out around Wellington Bay, the Bay of Quinte and Big Island, showing a familiar affinity for ice rather the flat, open farmland on Prince Edward. The bays around Prince Edward are among the few places in Lake Ontario still frozen.

5 Comments on “4/11 updates”

As a former raptor rehabilitator (coastal northern Lake Michigan), I’ve never considered a natural disturbance like a coastal winter storm as a killer of healthy owls. Sad but really interesting. Is this an unusually high number of drownings for snowies for a storm like this? Is the large number of deaths a combination of the storm severity and the fact that these were first year juveniles? Or is it common for snowies to drown in events like this and the larger numbers are just a reflection of the irruption? Just infinitely curious. Thanks!

I’d have to ask Norman Smith if in his 33 years of working with snowies he’s seen another incident of this magnitude. The impression I had from speaking with him was that this was a large number of drowned birds from one storm, but that losses to coastal storms were not unprecedented. It’s also worth remembering that many snowies were likely lost at sea in the early stages of this irruption. More than 300 were present at Cape Race, Newfoundland, in late November and early December, most (perhaps all) of which later departed out over the ocean, presumably lost. Remarkably, a few snowy owls wound up finding container ships crossing the north Atlantic around that time, and some traveled by ship all the way to the Netherlands. At least one also made it to Bermuda in early winter.

A huge storm is certainly a factor. I was on an Oregon beach following a spring storm with heavy rains and 80+ mph winds. I was amazed at the number of birds washed up on shore, including mergansers and rhinoceros auklets. All species that should have some sense as to surviving a storm on the ocean.

Aaaah yes, thank you. Interesting about the container ship birds. I joined after that so had not heard about this. I’ll stay tuned. Thanks for the great work!