Loren, tagged and marked with a smudge of green dye so she can be easily identified at a distance, is the newest SNOWstorm tagged owl. (©Guy Fitzgerald)

For the first time in this exceedingly slow winter, we have a newly tagged owl to introduce — Loren, an immature female in Québec.

After she showed up at the Montréal-Trudeau International Airport, she was trapped Jan. 25 by biologists from Falcon Environmental, which handles wildlife control at the airport — they have been great colleagues of our in years past. The owl was taken to Union Québécoise de Réhabilitation des Oiseaux de Proie (UQROP), the region’s main raptor rehab center, where Dr. Guy Fitzgerald examined her. He found her somewhat thin, so they kept her for about two weeks to bring her up to a good weight (a plump 2,100 grams), then fitted her with a transmitter and marked the bends of her wings with a dab of green dye so Falcon biologists can easily identify her from a distance if she returns to the airfield.

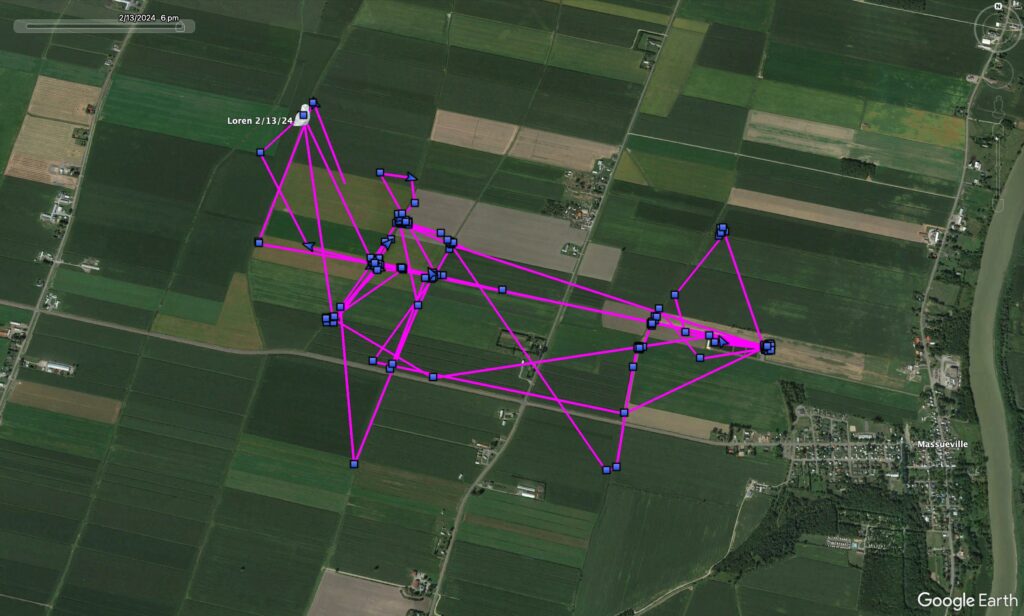

Loren was relocated 75 km (45 miles) away from the airport and released on Feb. 7 in farmland south of the St. Lawrence River near Masseuville, about 18 km (11 miles) southeast of Sorel-Tracy, QC, in an area where a number of our tagged owls have wintered in the past. She’s also been staying put, which is wonderful, because what we don’t want to see is a relocated owl boomeranging back to the airport. Her post-release data is part of our continuing work to understand how best to keep such owls away from planes.

So far, so good; Loren has stayed where they put her, far from the airport. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Loren’s transmitter was paid for through generous donations from the public to Project SNOWstorm, and her interactive map is up so you can follow her movements. (Like all our of maps, the updates are delayed by 24 hours to give her some breathing space from birders and photographers — an even bigger concern in a year like this when there are relatively few snowy owls for people to watch.)

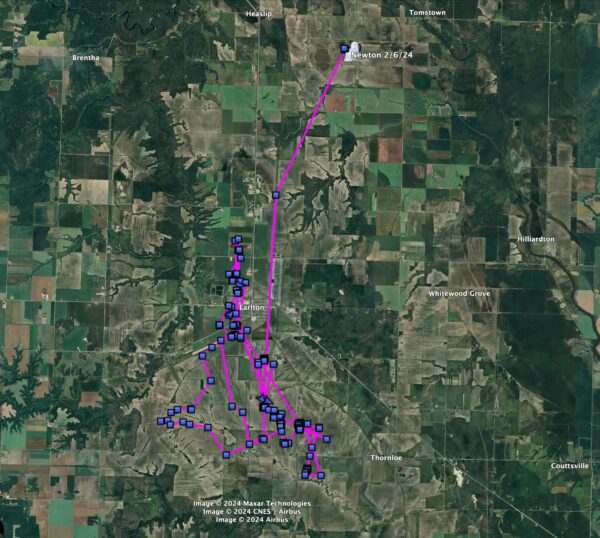

Before his transmitter slipped into sleep mode, Newton made a long direct flight north to a new area in eastern Ontario=. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

As for our other two tagged owls, Newton and Hochelaga, we are now passing through what we at SNOWstorm refer to as “the Valley of Death” — which isn’t as grim as it sounds! It just means that every year by about mid-February, the combination of low solar angle, short days and frequent wintertime cloud cover that further reduces solar recharge often causes the transmitters to drop below functional voltage and slip briefly into sleep mode. That’s what appears to have happened to both owls.

Newton, who last checked in Feb. 6, has missed the last two checks; his transmitter was at the time at 3.89 volts and falling. Newton had also left his hangout near Earlton, ON, and flown north about 11.25 km (7 miles) to near the villages of Tomstown and Heaslip. So it’s also possible he’s just in a spot with poor cell reception.

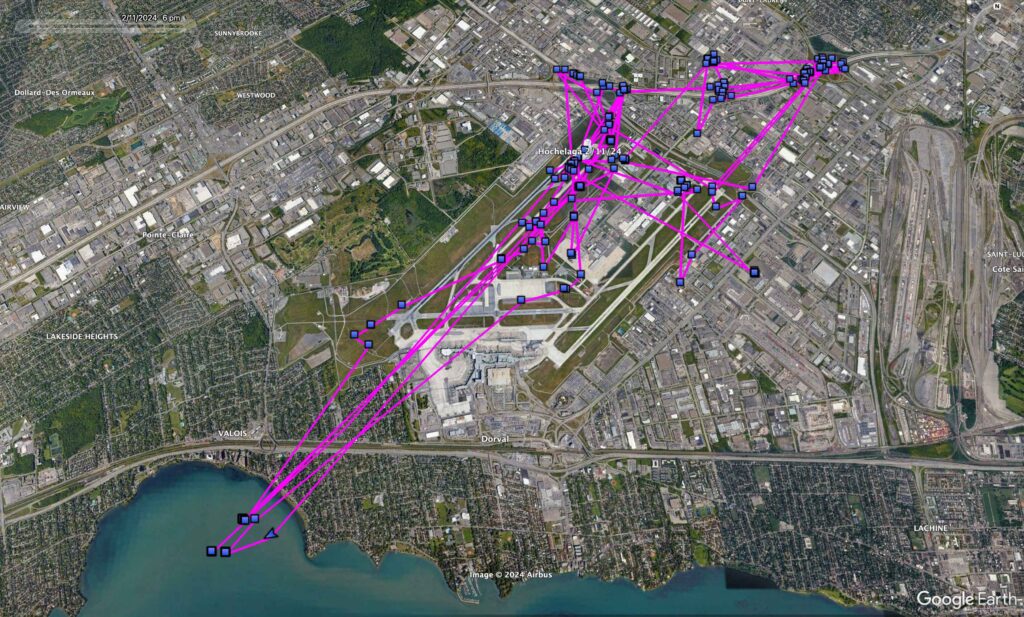

We’re trusting that after years of wintering in this same area, Hochelaga has learned how to stay out of trouble. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Hochelaga, on the other hand, had been hitting a more regular circuit between the Montréal-Trudeau International Airport and neighboring stretches of Autoroute 40, the Trans-Canada Highway. It’s the kind of environment that gives a snowy-owl researcher heart palpitations: airplanes, heavy highway traffic other hazards, but we know Hochelaga has been coming to this part of Montréal for years and at this point we just have to trust he knows how to stay out of danger.

He checked in Feb. 11 but missed Tuesday evening, Feb. 13; at last report his transmitter was at 3.70v, just above the 3.69v sleep mode cutoff, so we’re probably in the same situation with him as with Newton, and his transmitter is conserving power in sleep mode.

As I said, this is pretty common at this time of the year, especially in that part of southern Canada, which tends to be pretty cloudy all winter. The good news is that in the coming weeks, day length and solar angle both increase very rapidly, and we shouldn’t lose much movement data before the transmitters recharge and come back fully on line.

I said at the top that this has been a slow season, and in at least one way it’s unprecedented. Norman Smith with Massachusetts Audubon, who was a founding member of the SNOWstorm team, has been banding and relocating snowy owls from Boston’s Logan Airport since 1981. This has been the slowest winter in all 43 of his years there, with just a single snowy owl caught and moved from Logan, an adult female back in December. (There have also been only a handful of snowy owl reports anywhere along the Massachusetts coast, and the photos Norman has seen convinced him they were all the same owl, the one he transported from Logan.) Norman’s previous record low was four owls. By contrast, in 2013-14 he moved more than 150 snowies.

9 Comments on “Introducing Loren”

It saddens me to read that the numbers of snowy owls is just a trickle. What are your thoughts on why the number of Snowy owls is so low?

As we’ve mentioned a few times in the blog, we think there may be a couple of factors at play. There seems to have been little breeding activity in the Canadian Arctic last summer (although there was some — Loren was hatched this past summer, so somebody was having babies). That means there weren’t a lot of juvenile owls coming south, which is what normally makes up the bulk of a large irruption. The weather in the eastern Canadian Arctic and subarctic has been significantly warmer than usual this winter, which may also have kept snowies farther north than is often the case. For example, our tagged owl Otter, whom we watched via his unique hybrid GSM-satellite transmitter link, was still far up in the Arctic in autumn, before that link switched off the winter as it is programmed to do. The one concerning issue is the impact of avian influenza, which remains unknown. But numbers of snowy owls on the prairies in Saskatchewan were just a bit lower than average this winter, according to annual surveys there. So I don’t think the lack of owls in the East means something terrible has happened to snowy owls overall.

Thanks for the update and insight in your reply to the question.

That’s great news! Congratulations to everyone involve for her wellbeing .

This is some samples of what we can see of snowy owls who visit the Dorval airport and yes some

of them are not far from where Hochelaga went the last few days.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/BZiENX5NgcT3jwqb8

Thanks for the update Scott!! Welcome to the family Loren!!

Welcome Loren! She’s lovely! I hope she stays safe.

Thanks for sharing the amazing photos, Richard.

After worrying over the lack of breeding snowy owls, my friends and I in Washington State were surprised and delighted when three owls flew into Douglas County recently — in the same location as years past. Question for Scott: If the owls we see are usually juveniles, then we’re probably seeing different owls coming into the same area over the years. Any idea how they know to come to the same location, even the same streets, as the owls before them?

They’re not necessarily juveniles; they make up the majority of most large irruptions but in off-years many/most will be adults, and we’ve seen a great deal of site fidelity among some of our adults. Hochelaga, whom we’re tracking this winter, has been very faithful to the Montréal area, while Wells, whom we tagged in 2017, returned every year to the same part of Quebec City thereafter. Baltimore was so faithful to part of the Ottawa River Valley that we were able to find him two winters straight even after his transmitter failed, and eventually retrap him and remove the dead unit.