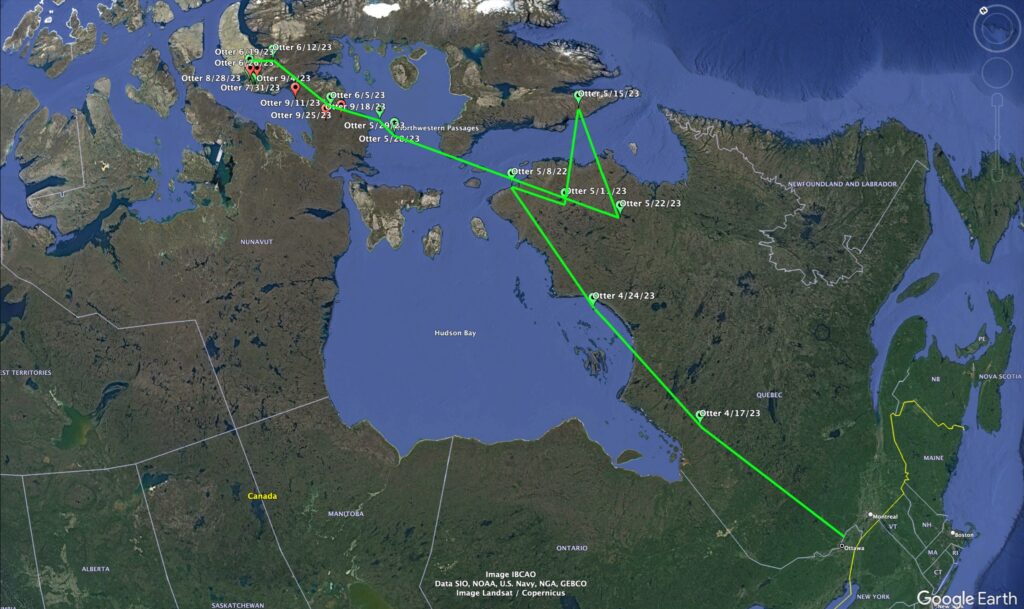

Otter’s spring 2023 migration, including his abortive first crossing to southern Baffin Island in May. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Once our tagged owls head north in the spring, that’s usually the last we hear from them until they come back south in the spring and re-enter the cell network, through which we communicate with their transmitters and obtain their data.

There is one exception: Otter.

First tagged in January 2019, this then-three-year-old adult male carries a hybrid transmitter. In addition to the usual cellular modem that works through the GSM network, Otter’s unit can also connect with the Argos satellite system, the more traditional approach to wildlife telemetry. His is the only one of several such then-experimental transmitters that has continued to work, almost five years after deployment.

That means that once Otter leaves the cell network in southern Canada (and any remote communities he might happen to pass on his way back to the Arctic, more and more of which now have cell service) we can continue to follow him — if not with the daily precision we get via the GSM transmitter in winter, then at least once a week, each Monday from March through the end of September, when we get a series of GPS coordinates for him.

This was the fifth summer we were able to follow Otter’s wanderings. After leaving his wintering site just northeast of Ottawa on April 9, he flew up to the east of James and Hudson Bays and on to the tip of the Ungava Peninsula in northern Québec. He appears to have had second thoughts about crossing the Hudson Strait on May 8 and turned back. He did cross briefly to Baffin Island on May 15, only to return south to the Ungava a week later. Eventually the pull north won out, though, and at the end of May Otter was on sea ice on the Foxe Basin south of Baffin Island, making landfall in early June on the Melville Peninsula and reaching the southwestern extreme of Baffin Island by June 19. In all, he migrated roughly 4,600 km (2,858 miles) north and west.

Otter’s summer and early autumn movements. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

One big question we always have is whether a tracked owl’s data suggests it has settled down to a breeding location. In Otter’s case this year, he appears not to have nested; his weekly locations, while lacking the granular detail of GPS/GSM data, show him moving around all summer in an area of about 500 sq. km (193 sq. miles), without the tick-tight fidelity to a single nest site.

This is in keeping with the reports we received from the Canadian Arctic this summer, which suggested a general lack of significant snowy owl breeding activity. (The one exception was a third-hand report we received, via our colleagues in Norway, that at least some snowy owls were breeding on Axel Heiberg Island, another 1,000 km [600 miles] north of Otter’s location.)

By Sept. 11 Otter was moving south again, back on the Melville Peninsula, where he remained Sept. 25, the last transmission we had via the Argos system. The duty cycle programmed into the Argos side of his transmitter runs from March 1 trough Sept. 30; we tried altering it last year with new commands to get year-round satellite data, but that caused a glitch, and rather than risk losing summer contact entirely, we restored the old duty cycle.

Our expectation is that Otter will come south into cell range again this winter, in which case we should get a full data dump of all of his high-resolution GPS locations since last April when he migrated north. But he’s fooled us once before, remaining off the grid in the subarctic of northern Labrador through the winter of 2020-21 and not coming south until the following autumn. Also, as cellular companies upgrade to 5G and decommission their 2G and 3G towers, older GSM transmitters like Otter’s that lack 5G capability may no longer be able to communicate with the cell system — though older, lower-G towers should remain operational in more remote areas of Canada for a while longer.

13 Comments on “Otter’s Summer Ramble”

Always wonderful to get updates. Scott, your writing makes for exciting adventure stories about our favorite characters. Thanks to the team for their devoted work and keeping us updated.

So interesting to see the tracked bird’s travels!! Thanks!

Please explain lack of breeding activity.

Jim Williams

Wayzata Minnesota

Birding columnist

Minneapolis StarTribune

Please explain lack of breeding activity.

Jim Williams

Wayzata Minnesota

Birding columnist

Minneapolis StarTribune

Please explain lack of breeding activity.

Jim Williams

Wayzata Minnesota

Birding columnist

Minneapolis StarTribune

I’ll take a stab at the minimal breeding issue: Lack of food sources?

We are all witnessing firsthand the negative impact of climate change. Is this also an issue with the actual breeding areas?

Can you give us a recap of approximately how many owls are currently fitted with working transmitters and known to be alive?

As usual, the detailed updates along with the fieldwork is much appreciated and fascinating to read. These owls are such special creatures. Thank you all for your efforts.

Sorry, I probably should have been clearer regarding breeding activity, and the apparent lack of it. This is not unusual for snowy owls, which tend to breed as a result of a localized boom in small mammal (primarily lemming) populations, and wander very widely from summer to summer looking for such lemming peaks — it’s not unusual for a snowy owl to move a couple thousand kilometers from one summer to the next.

It’s also not unusual for a year or two (or more) to pass without a major lemming peak, and thus no significant snowy owl breeding activity. The birds make up for this by producing a lot of young when they do find a rodent peak. I’d also caution that the Arctic is a very big place; the number of locations where scientists are monitoring for snowy owl nesting are very few, and while there are lots of remote communities in the North, we don’t have a way of soliciting information from them regarding the presence of nesting owls. (These folks usually have more urgent concerns than acting as eyes for a bunch of scientists from far away.)

So we shouldn’t be too alarmed by the lack of known nesting activity this past summer, nor should we immediately assume it’s connected to climate change. Climate change certainly poses challenges for snowy owls, but ironically one effect of in the central and eastern Canadian Arctic has been (at least for now) colder and snowier weather in late winter and spring. While this has been detrimental to, for example, long-distance migrant shorebirds like godwits, and nesting waterfowl, there has been speculation this may actually be improving conditions for lemmings in this part of the snowy owl’s range.

To answer Elaine’s question regarding how many owls are known to be alive with working transmitters, the answer is: we don’t know. Because the transmitters communicate via GSM cell networks, when the owls (other than Otter) are in the north and off the grid, we have no way of knowing where they are or what their status is. Over the years, we averaged about nine or 10 snowies from previous years returning south, but that changed dramatically last winter, when only three tagged owls reappeared. Given the known impact of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) on snowy owls, we have to conclude we lost a significant number of our tagged owls to the disease. (Because snowy owls feed heavily on flocking waterbirds like ducks and gulls, which have been major HPAI vectors, they are exposed to it at high rates.) Whether that will again be the case this winter we’ll have to see.

We had a total of six tagged owls last winter, three returning birds (Alderbrooke, Otter and Columbia) and three newly tagged (Huron, Newton and Salyer). We know Otter was hale and hearty at the end of September, but we haven’t heard from the others since they went north in spring, so all we can do is wait and see. (BTW, we have not used more of the hybrid GSM-Argos transmitters like Otter’s because we found that the external antenna required for the Argos connection was a weak link — snowy owls tended to tear it lose.)

Things are looking very slow for eastern Ontario to western Quebec which I think is attributable to a poor breeding season up north. Usually by end of November we see a number of snowy owls in the Ottawa area. Almost no reports so far and it is reminding me of winter 2010 to 2011 when very few snowy owls showed up in our area.

Thanks for the very interesting update on Otter’s travels and the breeding ups and downs of snowy owls. Looking forward to him returning to cell range this winter.!!

Thanks for the wonderful information!!!

Thank you for this wonderful website on Snowys! Hopefully we will have a Snowy visit Rhode Island this winter! I love to photograph them, with care an consideration for them. Have many photos!

Chris Powell, Jamestown, RI

Thank you for keeping us updated, appreciate all of the information you share.

Always love reading the latest information provided by you on their status. Thank you for clarifying their current status this season and reasons why we have not had any sightings in our region on the shores of Lake Erie .