Welcome back, everyone, to the start of Project SNOWstorm’s eighth season of snowy owl tracking and research — and the timing is perfect, because in the past few days we’ve heard from three of our returning snowies, back south after a summer in the Arctic and subarctic.

We also have news on what a fourth owl — Otter, who has a GPS/Argos satellite hybrid transmitter — was up to all summer in the north.

In fact, there’s a lot to update the SNOWstorm community on, because while the owls were up in the Arctic breeding, we were busy down here working on a lot of exciting developments, from newly published research based on our millions of points of GPS tracking data, our rapidly growing understanding of snowy owl health and threats, and our work on airport relocations, to a new project we’re helping to launch with globally important implications for snowy owl conservation.

In coming updates we’ll share details on all of that, plus our plans for fresh research this winter, during what may be shaping up to be a significant irruption into the Northeast and upper Great Lakes, with reports as least as far south as Long Island, NY.

This time, though, let’s cover the news we at SNOWstorm have been expecting for the past couple of weeks: The return of previously tagged owls. Although we occasionally get a returnee checking in as early as mid-October, it’s usually right around now, the second or third week of November, that we start hearing from tagged snowies.

Wells, photographed in 2019 in Québec City. (©Simon Villenueve)

And right on schedule, the first one back this season was our old friend Wells, a veteran female initially tagged as an adult in January 2017 in Maine. Ever sincethen, she’s wintered in and around Québec City, QC, but her summers have been all over the map. In 2017 and 2020 she summered in the Ungava Peninsula of northern Québec, but in 2018 and 2019 she migrated up into the central Canadian Arctic — not unusual behavior for snowy owls, which are quite nomadic in the breeding season, in search of high lemming populations to feed their chicks. (We’re also finding that her fidelity to her wintering grounds in Québec City is also typical of snowies, at least once they reach adulthood.)

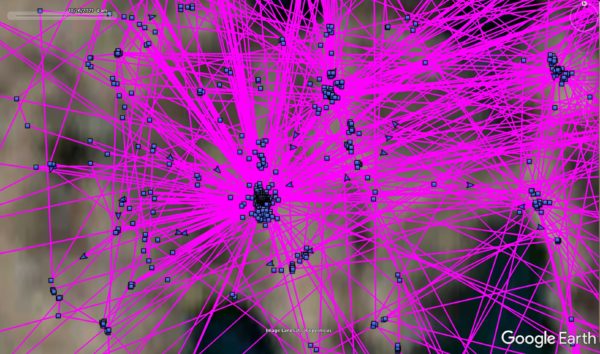

The core of Well’s nesting territory in 2021, showing roughly a 0.75 x 0.50 km area. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

This summer, Wells was back in the Ungava, where her tracking data make clear she nested about 40 km (21 miles) northeast of the Inuit community of Puvirnituq on Hudson Bay. As we noted last year, Wells’ transmitter is getting old and worn, and it’s having a harder and harder time dealing with the low sun angle and short days at this time of the year. We got about 9,000 GPS points from her memory banks, taking us through her position Oct. 25, when she was still far up in the Ungava, before the battery temporarily died.

Her position when she checked in Nov. 17 was on the south shore of the St. Lawrence, about 290 km (180 miles) east of Québec City. Hopefully her transmitter gets some sun and we’ll catch up on the remainder of her backlogged data. And I’m betting she’s already back in Québec City by now.

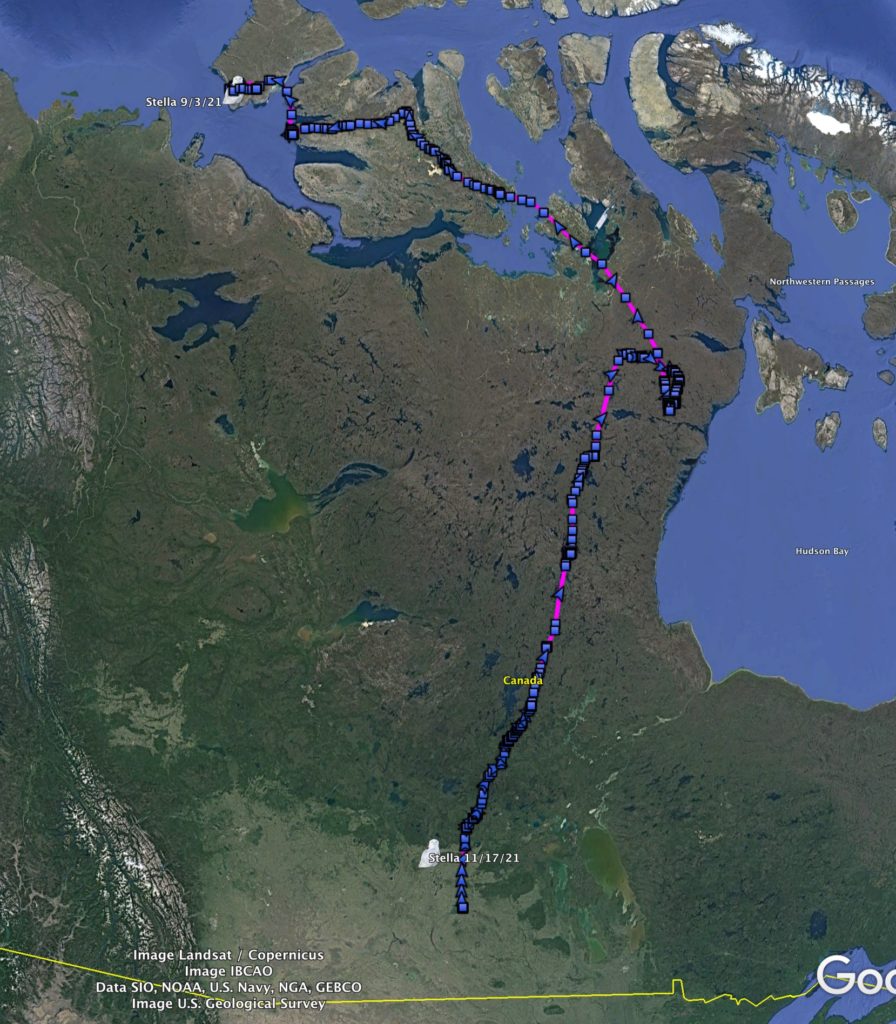

Stella was once again back in the far western Canadian Arctic archipelago in summer 2021. This map shows her northbound migration last spring and summer, and her current location in central Saskatchewan. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

On Thursday night, Nov. 18, two more snowies checked in at the same time. Stella, another longtime alum who was initially tagged in January 2018, uploaded part of her summer data from her current location in central Saskatchewan. Here again, her battery voltage wasn’t strong enough to send up everything in her unit’s memory banks, so we only have her movement data through early September, but we can see that this adult female also nested, this time on Banks Island, right on the western edge of the Canadian Arctic archipelago.

We don’t have her route south yet, but she checked in about 17 km (10 miles) north of Prince Albert, SK, in the transition zone between the aspen parkland ecosystem and the boreal forest just to its north. This is very close to her northbound route last spring, and broadly similar to her previous routes between the western Arctic archipelago and her wintering grounds in the northern Plains. In years past she’s wintered in eastern Montana and southern Manitoba — which was a dramatic change from the first winter we encountered her on Amherst Island in northeastern Lake Ontario.

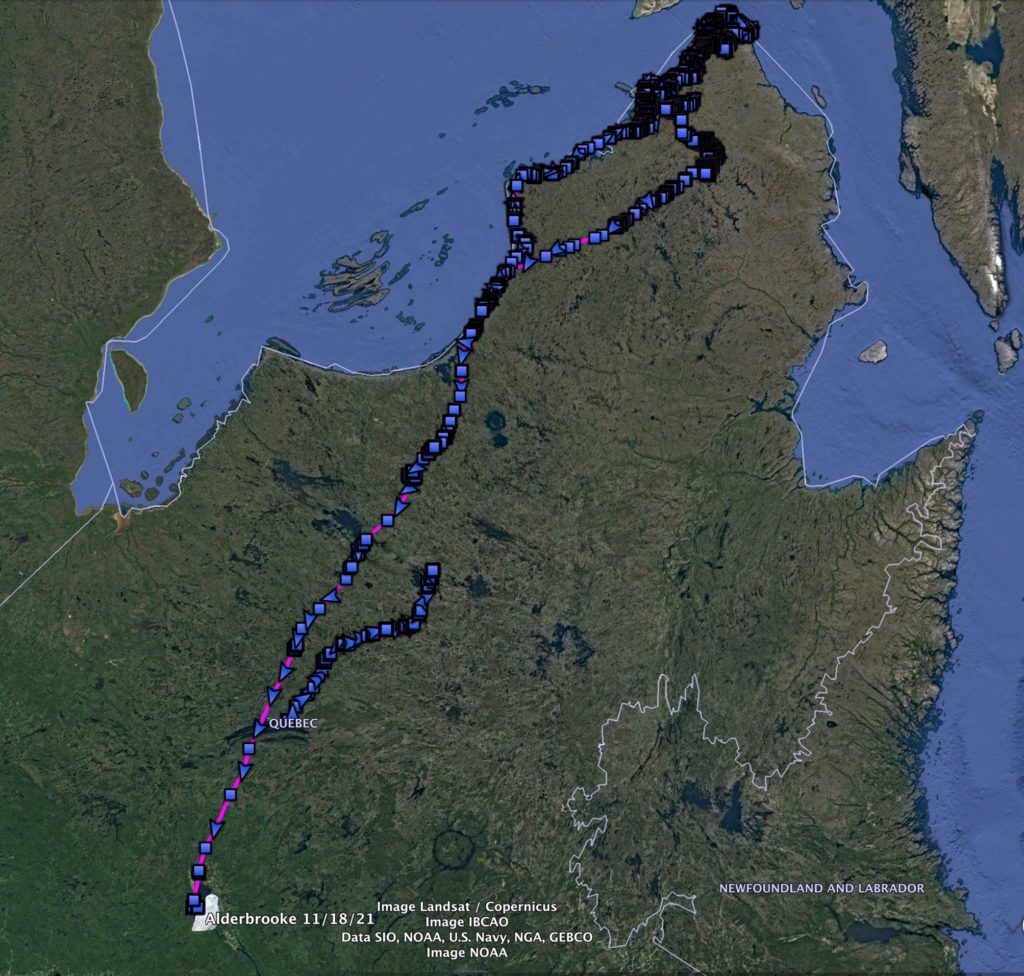

Still too young to breed, Alderbrooke spent last summer wandering all over the northern and western Ungava Peninsula. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The other returning owl is Alderbrooke, who was tagged as a juvenile female last winter. She was trapped by Falcon Environment at the Montréal airport, tagged, relocated and spent the winter on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. She summered this year in the western Ungava Peninsula, all the way up to Hudson Strait — but unlike Stella and Wells, she showed no sign of nesting. Instead of a dense concentration of thousands of GPS points in a small area around a nest site, Alderbrooke wandered all summer, which is what we’d expect from an owl not yet old enough to breed.

Alderbrooke, tagged and ready to go last winter in Montréal. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Her location on Thursday was along Lac Saint-Jean in southern Québec, about 175 km (110 miles) north of Québec City. Her newer transmitter has a more efficient solar panel, and her voltage was strong enough to upload her entire summer’s journey. Like those of Wells and Stella, all of her new data is already viewable in her interactive map.

Finally, we spent the summer keeping a weekly eye on Otter, the adult male tagged with a GPS/satellite hybrid transmitter in New York in January 2019. He didn’t come south into cell range last winter, but instead wintered in the Torngat Peninsula of northern Labrador. In April and May he migrated west and north across Hudson Bay, via Coats and Southampton islands, then up into the central Melville Peninsula, where the dense concentration of once-a-week Argos positions strongly suggests he was tending a mate and a nest.

Otter’s movements from his 2020-21 wintering site in the Torngat Peninsula of Labrador, across Hudson Bay and up to the Melville Peninsula. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Because of a hiccup in his duty cycle program, Otter’s transmitter only collects weekly Argos satellite positions from March 1-Sept. 30, so the latest position we have for him is Sept. 27, when he had just started moving south. However, if he comes down into cell range this winter, as he did in 2019-20 and 2020-21, two good things should happen. Otter’s transmitter should download a new duty cycle that’s been cued up and ready for him the past two years, and which will allow us to check up on him via the Argos satellites year-round. And he should also then upload to us the last 20 months’ worth of highly detailed, backlogged GPS data, which his transmitter will have been collecting and storing since he last checked in cellularly in April 2020.

(Unfortunately, Otter’s Argos data, which is collected on a completely different system than CTT’s GSM network, doesn’t transfer to our normal tracking maps, so Otter’s map currently only covers the period up to April 2020 — another reason to hope he comes south this winter.)

There’s lots more news to share, so stay tuned!

17 Comments on “A New Season, and Old Friends Return”

Exciting! Hope we have one come to Bayonne NJ like last year!!

Already one out on Star Island

We will be looking for an arctic visitor here in TN this winter!!

Thanks for all you do!!

We are hoping for some visitors to island Beach State Park, NJ. Thank you for your info!

There have been 3 sightings ( 3 different owls) on eastern LI. ( would rather not identify locations)

Waiting for them to show up at Presque Isle State Park, Erie Pa.

Thanks for the up date .

It’s been a bit of a slow start here in the northern plains (only two eBird reports of SNOWs in all of ND, both along the eastern edge), but we’re all geared-up and waiting for Snowies!

Absolutely fascinating stuff. So glad I found this site!!

A Snowy was seen on Cape Cod recently! Hoping to find a tagged Snowy this winter.

Looking forward to the updates. Great work.

Great news ! Gonna try to find her again (wells) :-)

Great to hear snowy owls season is in progress! On our neck of the woods we’ve seen only one so far. Exciting that Stella nested :)

Nice update on the winged wonders! So happy to know there may have been successful nests! Hope springs eternal to see a Snowy this winter! Thank you for all your efforts!

2 snowy’s on Amherst Island spotted today ❤️

One has been sighted in Lorain, Ohio but have not seen it.

I have a photo that I took in 2018 near the New Jersey shore. This owl appears to have a tracker on it and this is when Sinepuxent was in the area. Any news on this bird?

Sinepuxent was a juvenile female when she was tagged in 2018, and we never heard from her again once she headed north that spring. That’s not untypical of young snowies, and we know that their first migration can be a dangerous time. (Though we also know some owls spend multiple years in the north without coming south, so there’s always hope.) But the lower juvenile survival rate is one reason we now focus our general tagging efforts primarily on adults, which have proven that they’re survivors — although we do still tag first-winter owls in some cases, as for our airport relocation studies.

Two so far reported in Erie, PA at frequently visited sites. Hoping more will arrive!