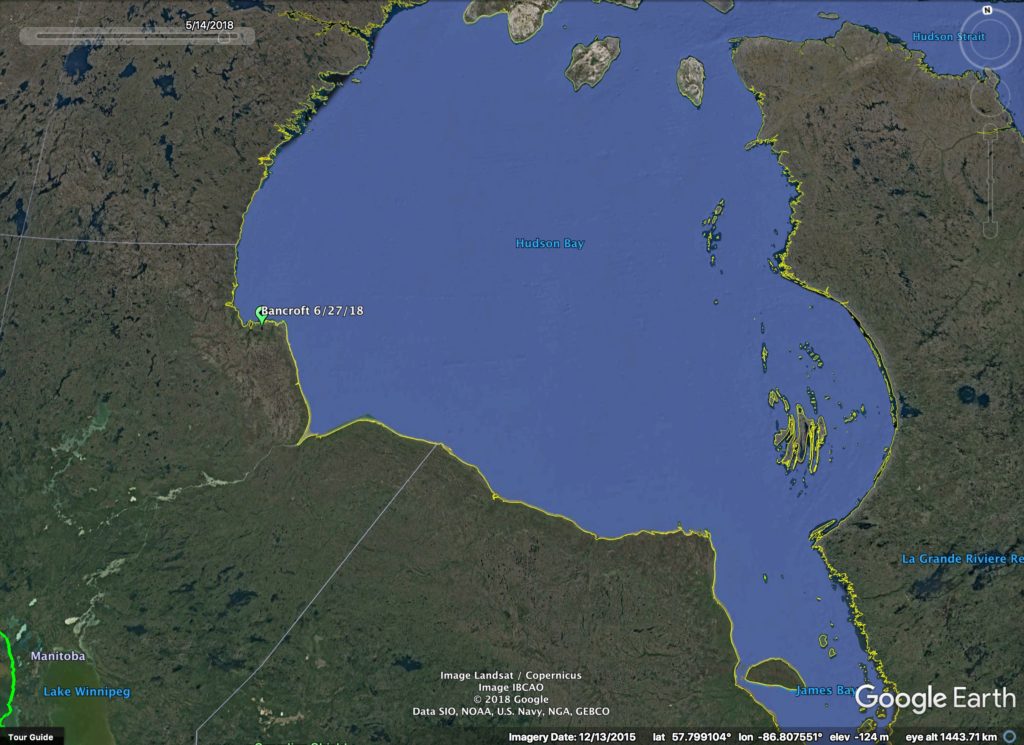

A few of Bancroft’s new neighbors. (©Scott Weidensaul)

The growing number of cell towers in the subarctic and Arctic means that summer is no longer a time of complete radio blackout for our GSM-tagged owls — though it’s still a pretty rare (and therefore exciting) occasion when we hear from one on the breeding grounds.

On June 27 Bancroft — a young male tagged near Coddington, Wisconsin, in January — checked in the western shore of Hudson Bay near Churchill, Manitoba, home of the famed autumn gathering of polar bears. It was a poor cell connection; he was about 23 km (15 miles) from the two cell towers that service the town, so we only got part of his northbound tracking data, but we did get his current location.

There are a few towers even farther north along the bay, so if he keeps moving we may get lucky again. On the other hand, he may settle down for the summer there — watching as the polar bears come in off the melting summer ice and begin their months-long “walking hibernation,” not feeding again until the sea ice forms in November and they can return to the ice to hunt seals.

(No further transmissions from Austin, who was last heard from June 8 on Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories.)

Churchill just out into the western shore of Hudson Bay, and a number of our tagged owls from the western Great Lakes have flown through or past it. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

* * * * *

Anytime we lose an owl it’s tough, but last month we lost one of our very first — Erie, the fourth bird we ever tagged, and one that gave us some incredible insights into snowy owl behavior and ecology.

Erie was captured the night of Jan. 19, 2014, at the Erie (PA) International Airport, along with a second owl, also an immature male, that we nicknamed Millcreek. Tom McDonald and CTT founder Mike Lanzone fitted Erie with a transmitter sponsored by the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology, and after their release, Erie and Millcreek spent most of the winter out on the frozen surface of Lake Erie, moving for weeks at a time many miles offshore, apparently hunting waterbirds in transient openings in the ice pack. It was the first time anyone had documented this behavior in snowy owls on the Great Lakes — a mirror of behavior that had only been recently shown in some adult snowies that spend the winter on Arctic sea ice, hunting waterbird-rich openings called polynyas.

Erie summered in 2014 along the southern edge of Hudson Bay — at one point, apparently riding on wind- and tide-drifted icebergs — and in the winter of 2014-15 came south again, mostly haunting the southern shores of Lake Huron.

In February 2016 Erie checked in from southern Ontario, but his transmitter malfunctioned later that winter, and attempts to trap him and remove it were unsuccessful. That was the last we knew of him, until last month, when we were contacted by Joe Valentine, a wildlife staffer with the Michigan Dept. of Natural Resources.

Around June 1, farmer in the northeast corner of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, near Presque Isle, noticed a snowy owl acting ill, and when he discovered it dead two days later called DNR. They saw the transmitter (which has our contact information on the side) and got in touch with us. Erie was frozen and sent to the DNR Wildlife Disease Lab in Lansing, where a necropsy was preformed this month. The findings weren’t definitive; he was emaciated, with parasitic worms in his abdominal cavity, and his lungs were heavily congested with fluid. I had initially assumed he might have been struck by a vehicle, because Joe said the transmitter appeared to have been damaged, but X-rays showed no broken bones. Dr. Erica Miller, who is part of Project SNOWstorm’s veterinary and pathology team and reviewed DNR’s, thinks Erie was suffering from a chronic illness, possibly due to a toxin. (The DNR lab was unable to perform lab tests on Erie’s tissues, so we’ll never know for sure.)

The transmitter has been shipped back to CTT, and while there is a chance that it may contain stored data, the fact that it was damaged at some point in the past makes that unlikely — in fact, that damage may be the reason it stopped sending data in 2016. If we’re able to add more to this story, we will. But we feel we’ve lost an old friend, one who showed us in dramatic fashion how little we knew about snowy owls. As a five-year-old Erie should have been old enough to breed the past summer or two, so we hope he left some offspring up on the tundra to continue his line.

We deeply appreciate the cooperation of DNR biologist Joe Valentine and the Michigan DNR Wildlife Disease Lab in Lansing for their cooperation and assistance. We’d also like to acknowledge again the support of the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology, which sponsored Erie’s transmitter, and all the PSO members who followed eagerly Erie’s movements in the years since then.

3 Comments on “A Postcard from Churchill, and an Old Friend Gone”

Hi, The last four up-date e-mails I have not been able to see any of the pictures …

Thanks for the up dates

Seems Bancroft is in good company with all the polar bears around. It’s very exciting to get updates of the whereabouts of the snowies at this time of year.

So sad to hear Erie is gone :( but as you say, all he has taught us remains.

It is interesting to see the number of snowy owls who have stayed south this winter. At least two are still on Amherst Island, Ontario and another was in Bath.

Field mice are extremely plentiful this year.