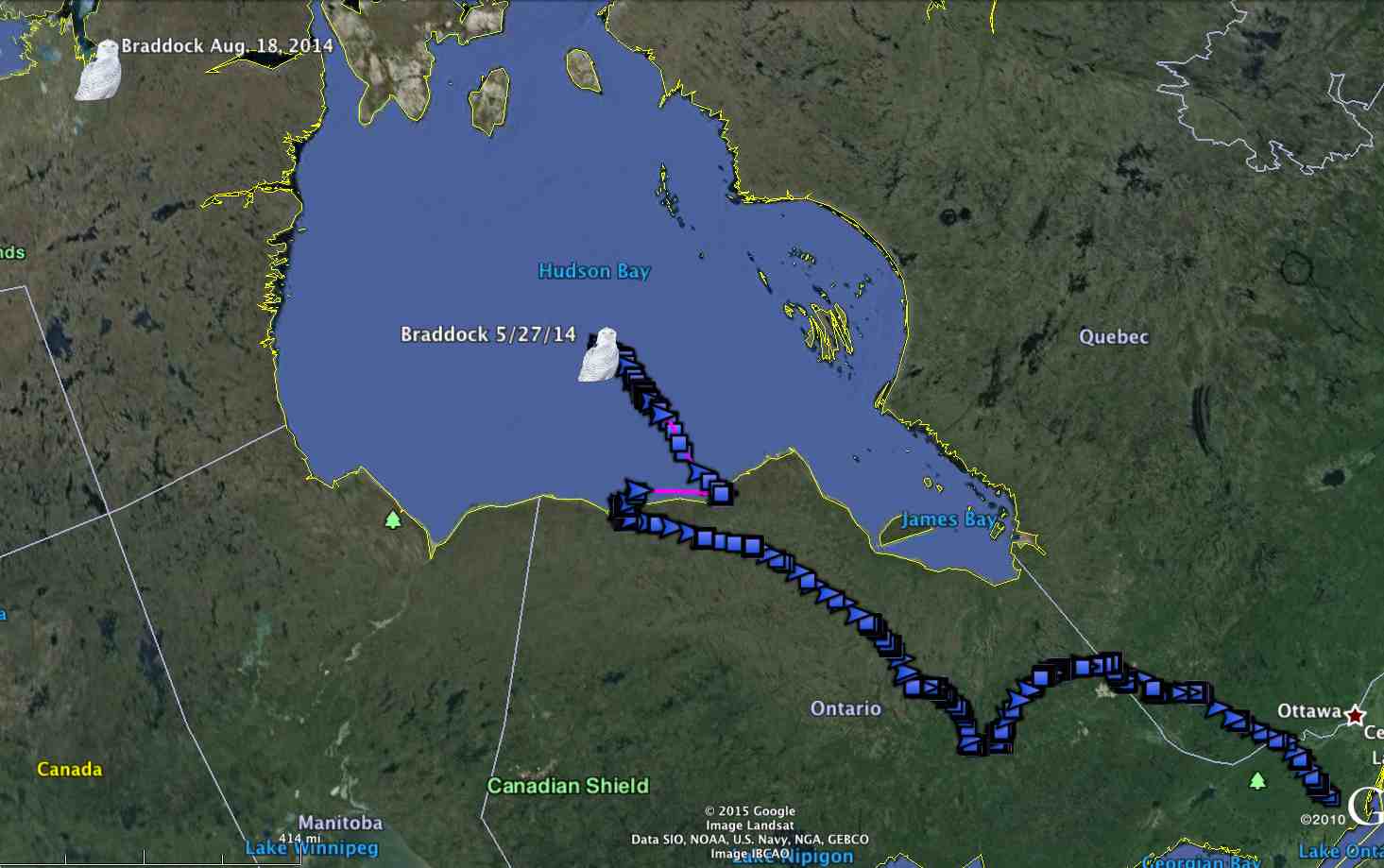

Braddock, the latest of the 2013-14 class of snowy owls to reappear, was ice-riding on his way to northern Nunavut last summer. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

To our surprise and delight, another of last winter’s owls has reappeared — Braddock, banded and tagged by Tom McDonald near Braddock Bay, on the Lake Ontario shore of New York, on Jan. 25, 2014.

Braddock spent last winter on and around Lake Ontario, moving between the lake ice and shore. In spring he began moving northwest across Lake Ontario and up the length of Georgian Bay, then returned southeast to Lake Simcoe and Lake Ontario, before starting north again in mid-April. He was last detected April 14 in southeastern Ontario.

That was it — until Sunday morning, as I was running some errands, when my cell phone buzzed with an automated text message: “CTT Data Update: Unit #89014103256345345838 (Braddock – SY Male) has checked in.”

Braddock, newly fitted with his transmitter last winter, comes out of the holding box and heads back out onto Braddock Bay. (©Aaron Winters)

A few moments later I got another text, this time from fellow SNOWstormer Steve Huy, a man of few words: “Insane owl location!”

The reason was the “current location” coordinates for Braddock that were included in the text– 67.060928N, 95.69620W. Plug that into your GPS or Google Earth, and it will take you to a spot between Franklin Lake and the Rasmussen Basin.

Not familiar with those names? Maybe that’s because they lie in the northern extremes of Nunavut, about 1,800 miles (2,900 km) northwest of where Braddock was tagged. Insane, indeed.

I raced home, and downloaded the first batch of data from Braddock’s transmitter. (It will take several more transmission cycles to extract all the stored data from the past nine months or more.) And reality was setting in. There’s no way, I realized, that a solar-power transmitter was sending data in the middle of the perpetual night of the Arctic winter — and besides, the closest Inuit village where there could conceivably be a cell tower was more than 100 miles (162 km) from that lonely spot on the tundra.

Braddock’s data showed his northward migration, though. Leaving southeastern Ontario on April 14, he moved rapidly north, crossing western Quebec and back into central Ontario over the course of a week or so, then arcing to the north and west across northern Ontario in early May. Finally, on May 11, he finally hit Hudson Bay.

(Interestingly, about a month later Erie, another of our returning owls, crossed Braddock’s path on his own way to Hudson Bay in early June.)

Once on the bay, Braddock moved onto the still-frozen water, then looped to land again for a couple of weeks. This was in Polar Bear Provincial Park, only about 30 miles (50 km) west of where Erie would be spending time a few weeks later.

Those neatly spaced, 30-minute locations arcing across Hudson Bay mean just one thing — Braddock was riding on ice floes or icebergs, pushed by wind and tide. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

On May 23 Braddock moved purposefully north on what was likely still solid ice, but on May 26 his tracks change, and for the next two days we see the very familiar, instantly recognizable pattern of an owl drifting on ice, with the 30-minute locations spaced with almost mathematical precision as the ice floes were pushed by wind and tide.

This first transmission’s data ended May 27, and we’re hoping for another 1,700 or so locations (about 45 days’ worth of data, the usual size of a transmission) this week.

But what about that insane “current location” up in Nunavut?

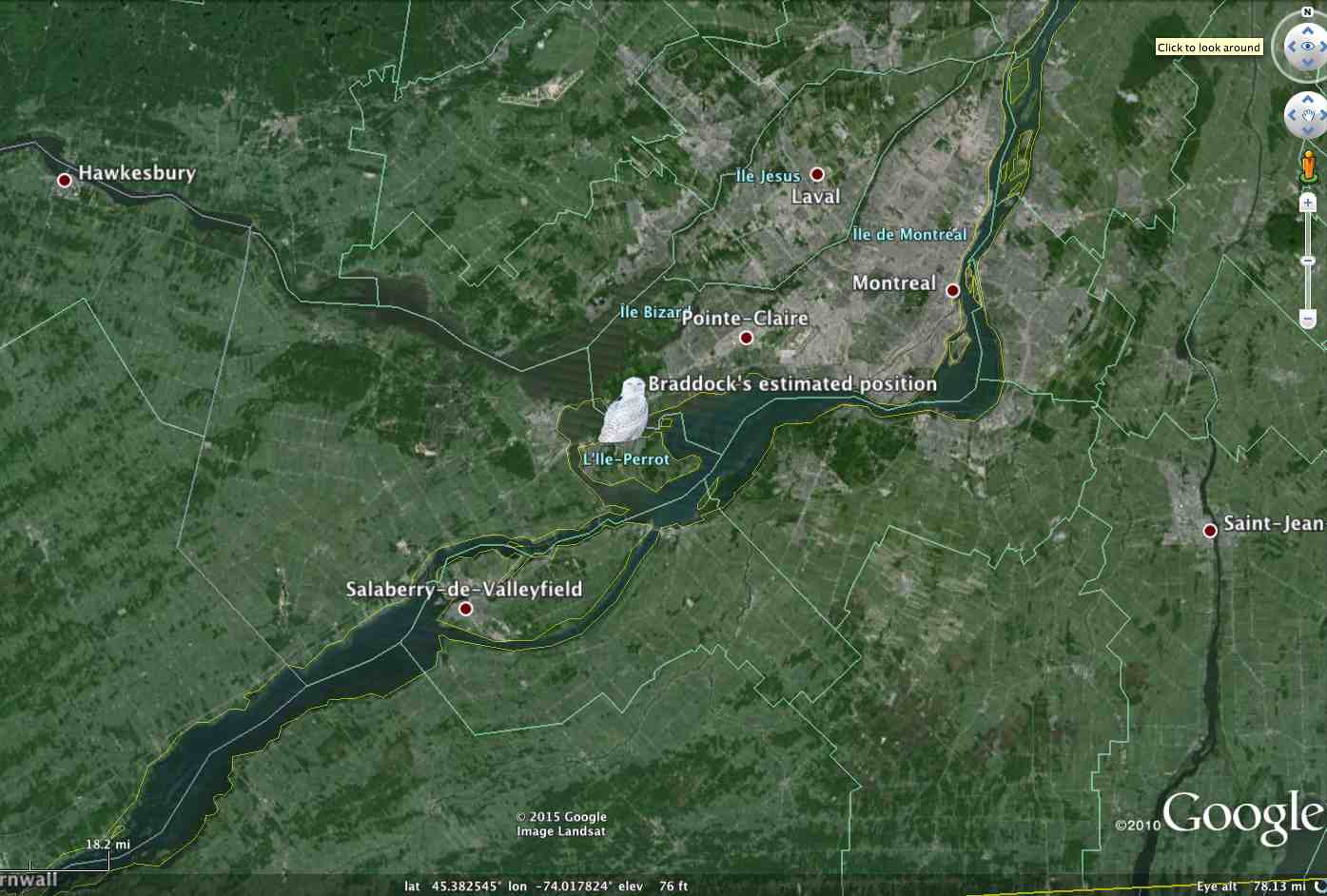

Andy McGann and Mike Lanzone at CTT aren’t sure why the transmitter sent that as the current site, but by looking at the data from the transmission, Mike is reasonably sure the owl actually checked in via a cell tower in the Montreal area. That Nunavut location, Mike discovered, was actually from August 18 — a preview, so to speak, of the rest of Braddock’s summer’s travels.

Braddock’s estimated current location, just southwest of Montreal (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

We’re not sure where else he went, but we know he made it at least that far north — the most northerly of the four owls who have come back this winter trailing fascinating data in their wake.

We’ve updated Braddock’s map, so you can explore his movements yourself, and as soon as we got more data from him, we’ll add it to the map.

4 Comments on “Braddock’s Back”

Randy Wilcox

WOWWIE! Love your work. The posts are riveting. Thanks for the updates!

Wow!

Wow!! Incredible!