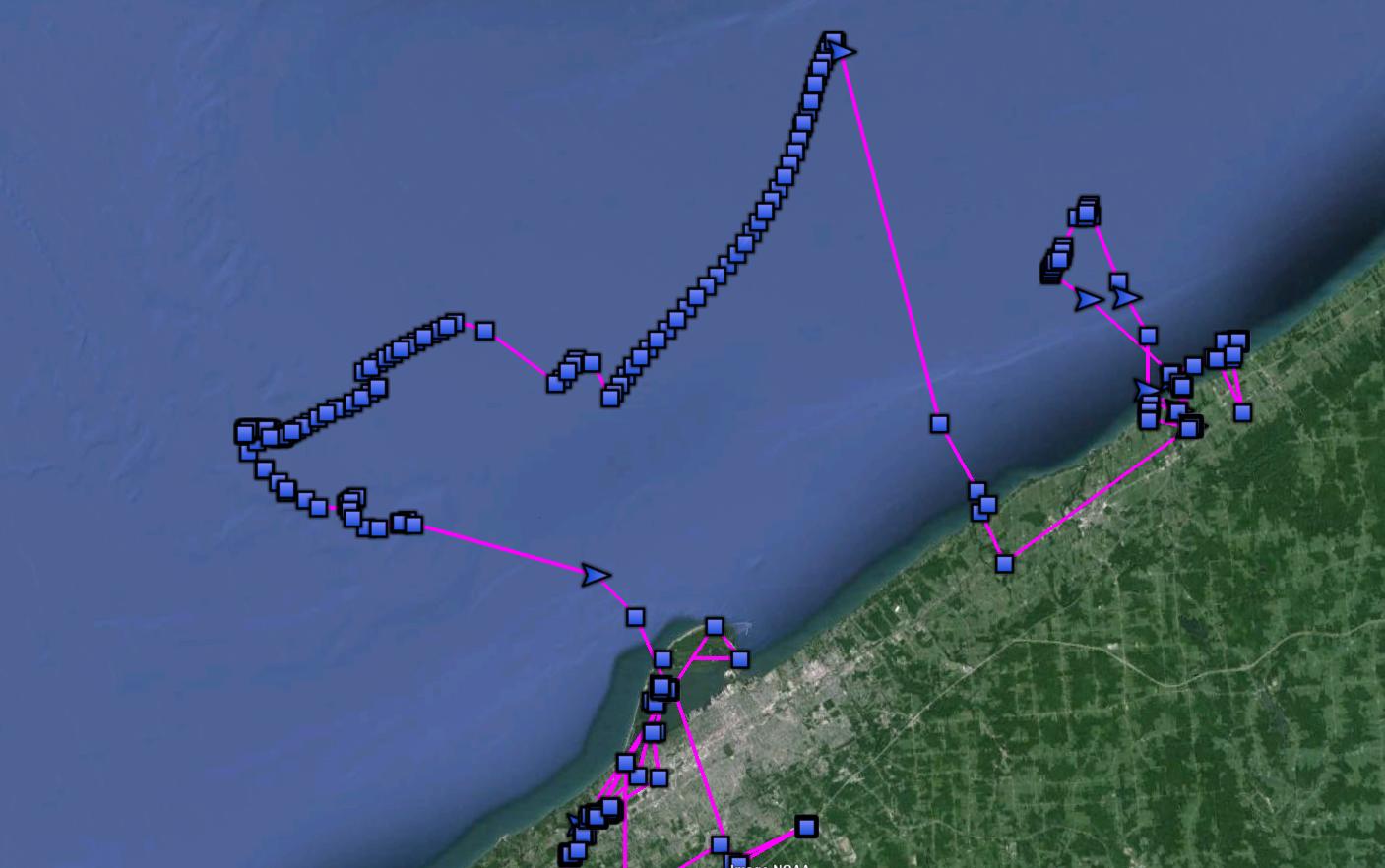

We’ve been waiting to hear from Erie, one of our tagged birds in northwestern Pennsylvania, but I suspect he’s in a place with poor cell reception — the middle of Lake Erie somewhere.

Erie’s been especially fun to follow because he’s already made several long voyages, so to speak, on wind-drifted ice sheets on the lake. Last month he spent three days out on the ice, drifting into Canadian waters before coming back to land, then making another, shorter sojourn on ice. The last time his transmitter checked in with Jan. 27, and he moving back offshore again at that time. If you haven’t done so already, go check out his map.

But wait a minute — three days is one thing, but how likely is it that a terrestrial owl would spend more than a week on a frozen lake? What could he possibly be eating out there?

In fact, Erie’s behavior is an echo of one of the most interesting discoveries about snowy owls in recent years. Jean-François Therrien, the senior research biologist at Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania (and one of the Project SNOWstorm team) has been studying snowies in the Canadian Arctic for years.

J.F. and his colleagues have tagged adult snowy owls with traditional satellite tags, and found to their shock that some of the owls actually went north in the winter — up to Bylot Island in the territory of Nunavut. They stayed through the perpetual darkness of the Arctic winter, far out on the pack ice.

It appears the owls are gathering around polynyas and leads, cracks of open water in the pack ice. These openings are known to hold large numbers of eiders, long-tailed ducks and black guillemots, on which the owls are presumably preying.

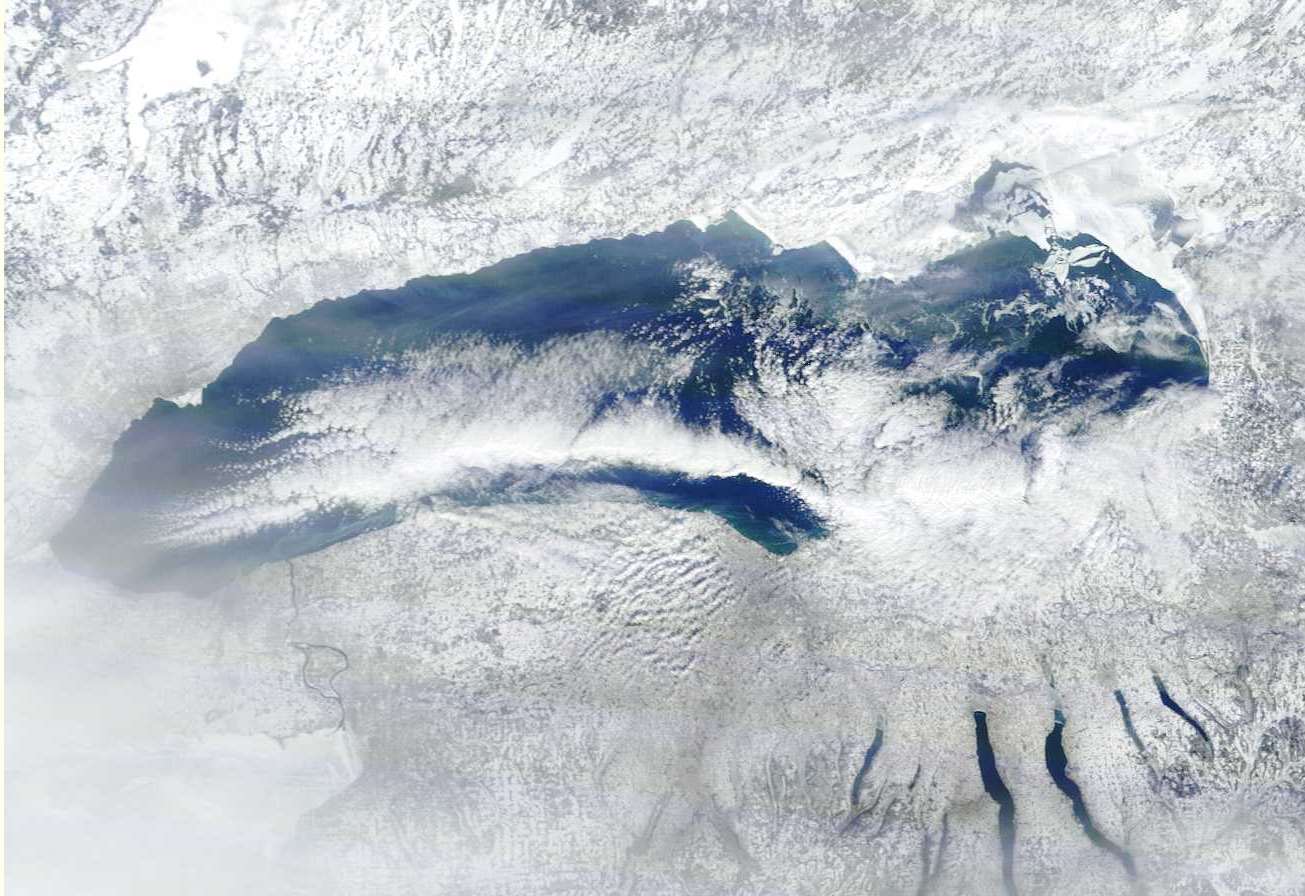

Erie may well be doing the same thing. Although Lake Erie is largely frozen, it isn’t a single block of ice. Rather, winds keep shifting and cracking enormous ice plates, as you can see in this satellite photo from a couple days ago, when the clouds were clear enough to see the surface.

The ice cover on Lake Erie isn’t a solid sheet, but rather huge ice plates that open and close as the wind pushes them. (NOAA CoastWatch imagery)

When the winds shift, they open and close the leads of open water — sometimes opening along the southern shore, sometimes (as in this image, when the wind was from the north) along the Canadian side.

We don’t know how many waterbirds are using those open cracks, but apparently Erie and several of other owls have been finding food out there, because they spend a lot of time on or near the ice.

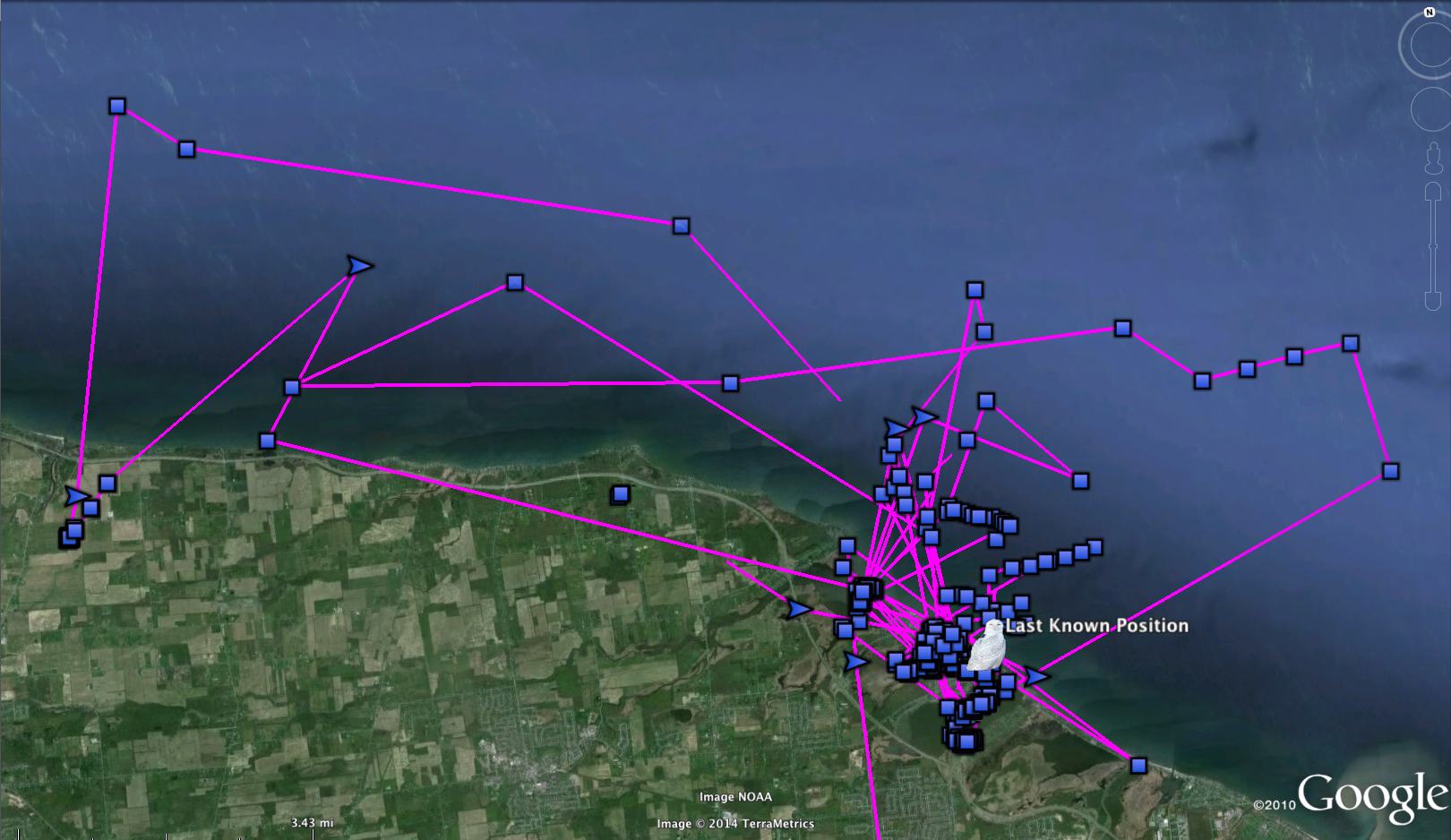

In contrast, Lake Ontario is a lot deeper, and a lot slower to freeze. The ice is largely restricted to a narrow band along the southern shore, which is why Braddock and Cranberry, our two New York lakeshore snowies, have only ventured a short distance offshore. But that may be a rich hunting ground, too, putting them within easy reach of ducks and other waterbirds.

8 Comments on “Snowies on Ice”

Wow! Just fascinating movement data captured on Erie! The inclusion of the actual satellite pictures of the ice packs on Lake Erie certainly seem to back up your hypotheses of the “why’s” and “where’s” Erie is spending his time, during his days’ long forays for food on the ice. He just seems to be going “with the flow”, quite literally.

Equally fascinating is how Braddock and Cranberry have adapted to the use of the ice around Lake Ontario’s coastline as a hunting and launching pad for their feeding forays!

Great data and insights by the Project SNOWstorm team. Many, many thanks.

That’s the way this project has been going — one surprising insight after another. And the winter’s only half over (plus we’re tagging new owls a couple of times a week), so who knows what else we’ll find. But in this particular case, we’re lucky the irruption coincided with an old-fashioned winter and lots of ice on the Great Lakes, or we might have missed the chance to document this behavior.

I’m a high school math teacher and would like to have my students make maps of your data…any chance you might be able to share an excel spreadsheet with me? Is there a place I can go to get the raw data?

Because we’ll be publishing this winter’s data in peer-reviewed journals, we need to be careful about how the raw data are used and disseminated, but it it’s for the classroom only, we’d be happy to work with teachers who might want to use it to inspire their students to an interest in science.

Interesting – as humans we think we know everything – it is amazing how little we actually know. Very cool information.

Thank you & all others devoting your time & energy to this important study. Thank you, Mr. Weidensaul, for sharing with us. You are my fav non-fiction author–in blog or in print!

It’s been an exciting ride for all of us involved with SNOWstorm. I find it hard to remember that as recently as the first week of December, none of us had any idea how our lives were going to be turned upside down this winter by this all-consuming project. I’ve never seen something of this magnitude come together so quickly, and with such extraordinary public support.