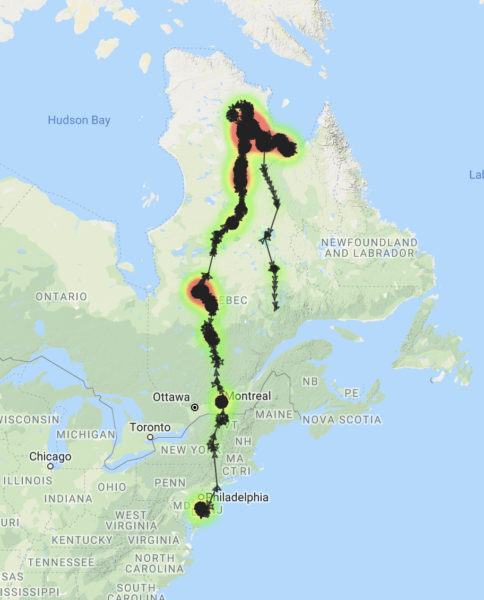

Worlds apart during this past summer, Wells and Island Beach have ended up in the same general area of Quebec in the past week. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Two more previously tagged owls are back south, having uploaded more than 12,000 GPS points showing where they’ve been over the past eight months — Wells and Island Beach, who went in dramatically different directions over the summer.

Wells is an adult female, originally trapped in 2017 by USDA Wildlife Services at the Portland (Maine) Jetport, tagged by SNOWstorm collaborators from the Biodiversity Research Center, and released Jan. 25, 2017 at Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in southern Maine.

In 2017 she summered (and apparently nested) in the Ungava Peninsula of northern Quebec, where a lot of snowy owls were breeding that year. She came south and spent last winter on the outskirts of Quebec City. We last had a transmission from her on April 23, 2018, at Lac St.-Jean, Quebec as she was heading north — back to the Ungava, we assumed.

Wells’ journey northwest, covering more than 9,100 km (5,654 miles) to and from the western Canadian Arctic. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Well, we were wrong. Instead, she angled northwest, arriving on the eastern side of Hudson Bay on April 29, then spending the next week crossing the presumably mostly frozen bay, some 780 km (420 miles). Some of the data points show the classic signs of an owl drifting on wind-driven ice, closely packed with very even spacing. Then she took to the wing and migrated up the western side of Hudson Bay through Nunavut to King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula in the Arctic Archipelago.

It doesn’t appear Wells nested this summer. She spent a long time getting to the northern point on her travels, and while she did settle down on King William Island it wasn’t until mid-July, too late to realistically have started a nest, nor did she restrict herself to a small, tight territory. By late September she was moving south, and for the next month and a half she followed the western shore of Hudson and James bays, finally reaching Akimiski Island in James Bay about Nov. 10. Crossing the lower bay, she turned almost due east and in about three days crossed southern Quebec, checking in Nov. 23 from just south of Port-Cartier, QC, on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River.

In all, Wells traveled more than 9,100 km (5,654 miles) between April and November, and the distance between her northwesternmost point and her current location is more than 2,700 km (1,660 miles). It’s interesting that while we saw a similarly dramatic east-west movement this summer by Stella, that owl opted to go straight south in Saskatchewan, while Wells headed back to the Atlantic coast. Why? You’d have to ask them, because we don’t have the answer. Snowy owls, we have found, are very much their own individuals.

Island Beach, on the other hand, stayed east for the summer. Having wintered along the mid-Atlantic coast (where we struggled to keep track of him, since his transmitter has had charging issues) this juvenile male moved north through southern Quebec, and last checked in May 16. Now we know he continued up into the Ungava Peninsula, ambling around with no particular destination; as a juvenile still at least two or three years from maturity, he had no place he needed to be.

Island Beach’s summer sojourn to the Ungava; this heat map shows, through yellows, oranges and reds, where he spent most of his time. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

By late August he was along the shores of Ungava Bay, then his unit when dark — probably because the fast-diminishing light in the subarctic autumn was too weak to keep it fully charged. It came back to life Nov. 9, however, by which time Island Beach was barreling south, covering 775 km (481 miles) in a few days. On Nov. 24 he was just south of Lac Manicouagan, the weird, ring-shaped lake that was created in the 1960s by flooding a crater left by a massive meteor strike 215 million years ago.

As for the other two returnee owls we’d mentioned in the last post, Pettibone remains in the same general area of central Saskatchewan as when he first checked in Nov. 7, just west of the town of Melfort. Stella, on the other hand, flew another 400 km (250 miles) due south, and on Nov. 21 was just 3.5 km (2 miles) north of the Montana border near — well, not really near anywhere, this being pretty empty ranch and farm country. She’s about 40 km (25 miles) southeast of Rockglen, SK, and the same distance northeast of Glentana, MT. If she crosses the border, she’ll be SNOWstorm’s first snowy owl in Big Sky Country.

We’ll have updated maps for Wells and Island Beach in the days ahead — check back to trace their routes north and south.

4 Comments on “Two More Back South”

What ever happened to Ramsey the snowy owl?

Ramsey headed north in April 2014, but we never heard from him after that. There are several possibilities; he may simply have remained north or in areas without cell service, as we know some snowies stay in the Arctic in winter — some actually move north onto the sea ice. His transmitter may have failed. Also here in the U.S. many cell providers have moved to 4G service, to which some of the earliest transmitters like Ramsey’s cannot link. (That’s less of an issue in Canada.) Finally — and this is especially possible because Ramsey was a young bird — he may not have survived to maturity. The juvenile mortality rate for young raptors in their first year averages more than 60 or 70 percent, depending on the species.

We’re working with CTT on a new style of transmitter that will incorporate both a GSM (cell-based) system like we’ve always used, which gives us such incredibly detailed data, along with an Argos satellite-enabled system to keep periodic track of the owl once it’s out of cell range. More on that soon. Such dual-system transmitters will help eliminate uncertainty about the fate of many tagged owls.

Please go to website

New England snowy owls an more owls

There is a photo from Scott Creamer of a snowy with a silver leg tag

Cannot see the # on tag

They didn’t disclose location hope it’s an owl you have banded

Scott Creamer does a lot of photography in southeastern Massachusetts, so there’s a good chance that any banded snowies he photographed were captured by SNOWstorm co-founder Norman Smith of Mass Audubon and relocated from Logan Airport for their safety.