Dave Brinker scans the whited-out landscape at Cat Island, Wisconsin, looking for owls. (©Paul Smith, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

We have two new owls to introduce — and a heck of story about how they were tagged, despite some of the worst weather this winter.

They are Badger and Arlington, and both are in Wisconsin. That represents a return to SNOWstorm’s roots, in a way, because the second owl we ever tagged in 2013, Buena Vista, was caught in the Badger State. Their story is also a good example of how the best-laid plans can go awry.

Wisconsin was one of first states to step up in a big way and support our work in 2013-14, and that’s been the case again this winter, with another significant irruption into the state. The Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Service Foundation have teamed up to sponsor two transmitters, Madison Audubon Society pledged to sponsor another, and the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology has put up funds to cover a fourth.

Our hope was to tag at least one owl near Madison Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary. We also wanted to deploy up to four transmitters on owls in the Cat Island chain at the southern end of Green Bay, a traditional early winter gathering spot for snowies. That would give us data on their interactions among each other, and then allow us to track them later in the winter when (as we expected) they would move either onto the frozen lake once the ice formed, or inland to the Fox River valley agricultural areas.

Tom Erdman (left) and Dave Brinker set a bownet on the Cat Island causeway. (©Paul Smith, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

So immediately after Christmas, SNOWstorm co-founder (and Wisconsin native) Dave Brinker headed west from his home in Maryland. Earlier in December, as many as 16 snowies had been seen regularly on Cat Island and the wave-barrier causeway surrounding this ambitious restoration area. Unfortunately, the weather had become bitterly cold over the holidays, and Green Bay had already begun to freeze — luring many of the owls offshore.

The first morning Dave met the rest of the trapping crew — longtime SNOWstorm collaborator Eugene Jacobs from Stevens Point, WI, and Eugene’s brother John; Tom Erdman, an experienced bander and retired curator at the University of Wisconsin’s Ritcher Museum of Natural History; wildlife biologists Tom Prestby and Gary Van Vreede; and Dave’s daughter, Laurel Brinker-Cole, and Dave’s cousin Mike Senn.

They searched the island chain and causeway, looking for owls in what were challenging conditions, to say the least. “It was a white-out day,” Dave said. “It was cloudy, with light snow — not terribly windy, but everything blended together, ice to snow to sky, so that there was no horizon. Just white.” This turned out to be the most pleasant weather of the field work, at 9 degrees Fahrenheit with a light wind.

The day before they arrived, four snowies were still present on the Cat Island complex, but that first day they were able to find only three, all of them flighty and difficult to approach. They made net sets on two, and managed to catch one, a juvenile male that, while in good condition, was felt to be a bit small to carry a transmitter, and so was banded but released untagged.

A juvenile male — a bit too small for a transmitter — was banded and measured out of the weather at the Barkhausen Waterfowl Preserve near Cat Island, then released where it was caught. (©Paul Smith, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

The next day the weather turned much worse, with 5 degree Fahrenheit cold and high winds. Eugene and his brother John elected to trap near Pulaski, WI, where they set up on both an immature female and likely an adult male, but were not able to lure either one in. Tom Erdman and Dave were working Cat Island again, but by that point only one of the original 16 owls remained. Part of the problem, Dave said, was that a nearby power plant creates an area of open water that attracts a large number of bald eagles, which spent a lot of time flushing and chasing the snowies — one reason the owls may have abandoned island chain. As dusk gathered, Dave made a last-minute run toward Freedom, WI, another area with several owls, but he was unable to find any before full dark.

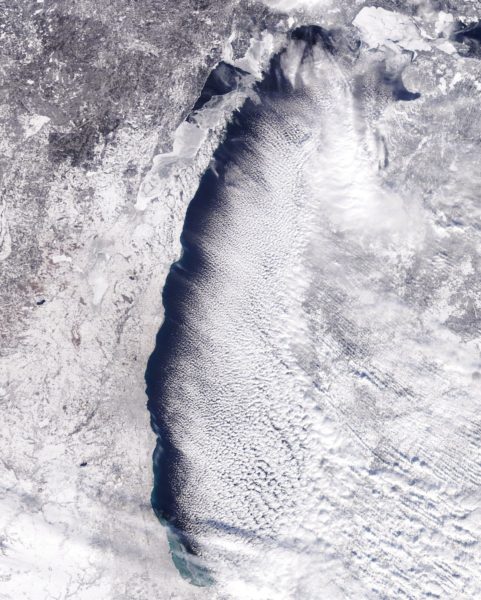

Lake-effect snow streams across Lake Michigan, with the frozen arm of Green Bay at the upper left of the lake. (NOAA CoastWatch imagery)

The last day — Saturday, Dec. 30 — Dave and his cousin Mike headed back to Freedom, in Outagamie County. “It was blue skies, brutally cold and windy — a high of 1F with 25 or 30 mile per hour winds,” he said. “It was not a pleasant day.” Late in the afternoon Mike had to leave, and Dave continued searching for owls on his own. It wasn’t until 3:30 p.m. that he located a juvenile female on a utility pole, but as he was setting up, she left. Soon thereafter, Dave spotted an almost white, probably adult male, but as he was preparing to set up the net a photographer pulled up, walked out of his vehicle to the base of the pole with his camera, and flushed the bird.

The sun was dropping fast, so Dave scrambled in the cold to located the dark female owl again — only to have the same photographer, along with a second vehicle, pull up on either side of him within just feet of the bownet. After a rather tense conversation with the photographers in which he explained what he was doing and asked for some cooperation, Dave moved once more, setting up on a juvenile male away from all of the recent eBird points near Freedom. At first the bird seemed to show some interest, but then it zoomed off in a different direction, catching a small rodent before vanishing in the dusk.

By now, the only light remaining was the glow along the western horizon — but it was enough so that Dave could check power poles as he drove along a road where he had seen a very dark juvenile female the morning before. He spotted the silhouette of a large owl on top of a pole, though Dave had to get fairly close to be sure it was the young female snowy again, and not a great horned owl. He set the bownet by the quiet roadside, close to a home with its garage door open and a truck warming up inside. Dave backed up from the net and used his headlights to illuminate the trap — and caught the female just as the couple that lived in the house pulled out of their driveway. (They were so delighted to see the owl up close that they flagged down another passing neighbor to share the experience with him.)

Dave Brinker with Badger, our first Wisconsin snowy of the season, just before her release near Freedom, WI. (©Mike Senn)

So that’s Badger, who was tagged that evening and released at her capture site the next morning. Her transmitter is one that the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Service Foundation have underwritten. She’s remained in a 0.7 square mile (1.8 sq. km) area since she was tagged — a location that’s only a few miles northeast of where one of our 2014 owls, Freedom, was wintering that year.

After the holidays, Eugene Jacobs, Tom Meyer (director of the Cedar Grove Ornithological Station) and one of Eugene’s interns picked up the effort despite continued intense cold. On Jan. 4 they caught two juvenile male snowies just south of the village of Arlington in southern Columbia County, on the former Arlington Prairie adjacent to Madison Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary. (If the name “Goose Pond” sounds familiar, it’s because Eugene released an adult male owl, relocated away from the Central Wisconsin Airport, there in 2015.)

Arlington, a juvenile male whose transmitter was underwritten by Madison Audubon Society. (©David Rihn)

One of the new birds, while healthy, was a bit small for a transmitter — because like most raptors snowy owls exhibit reverse sexual dimorphism, in which the males average smaller than the females, we’re especially picky about which ones we tag, to make sure the unit is just a few percent of the bird’s weight. But the second male, which weighed more than 1,800 grams (4 pounds), was an ideal candidate for a tag — and so we’re tracking “Arlington,” named for the town, the prairie and the Arlington Agricultural Research Center next door to the Audubon sanctuary, all of which he’s been using since he was tagged. The cost of his transmitter was generously underwritten by the members of Madison Audubon. Look for the maps for Badger and Arlington very soon.

And we’re not done, at least not if we can help it. Eugene and his colleagues are hoping to deploy up to three more transmitters in Wisconsin this winter, and he and Tom Meyer were back in the field Jan. 7 in the Buena Vista Grasslands south of Stevens Point. They weren’t successful, but they’re not through trying — though as the past couple of weeks in the Badger State have shown, it’s not always easy to make plans become a reality.

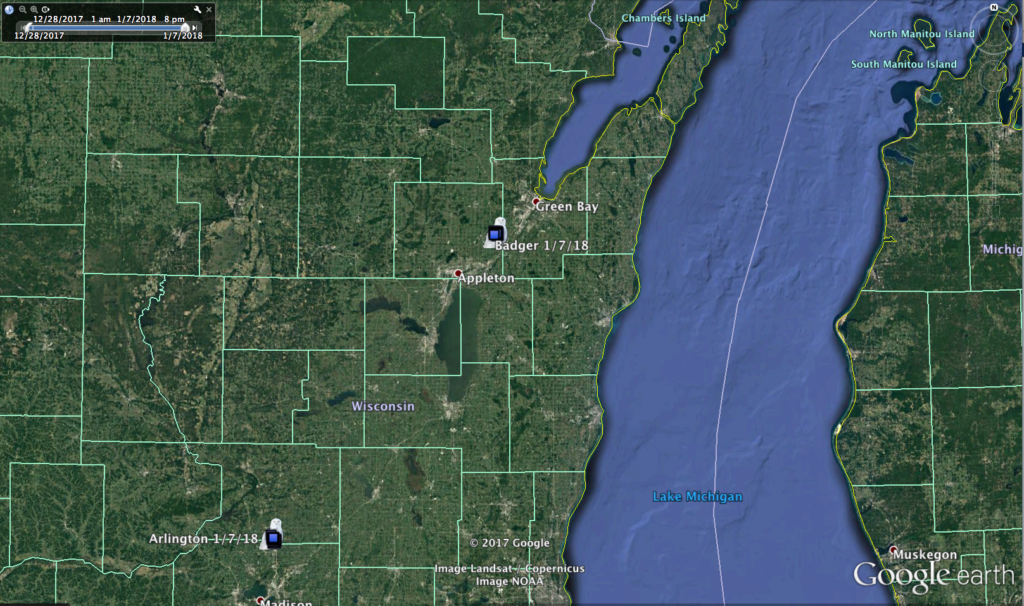

The general locations where Badger and Arlington are wintering. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

2 Comments on “Badger and Arlington Take the Stage”

Pingback: Tracking Wisconsin Snowy Owls - Austin and Badger

We have been fortunate to have a visitor hanging around for at least a month. See it every day lately. Had one in 2016 around as well, it liked the silo that we since tore down. Chances it’s same owl?

Near Mishicot, Wisconsin. https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/8efc2b960f3e89808356e0abd4232b7705d37425b326a80df0121a83d306c402.jpg https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/def519bdbca8a681d8f33f6065885055e3ab21fca0a6eda5d95ec912931a8e5a.jpg