Some of the tons of marsh vegetation, snow and ice through which the CTT team had to search to look for Higbee. (©Mike Lanzone)

For the second time this winter, we’ve lost a tagged owl — Higbee, one of the three juvenile males we’ve come to think of as the “Jersey Boys.” And while the immediate cause was a vehicle collision, it occurred during an historically big coastal storm that we initially believed all three owls had survived.

Mike Lanzone and Trish Miller preparing to release Higbee Dec. 5, 2017. (©Mark Garland)

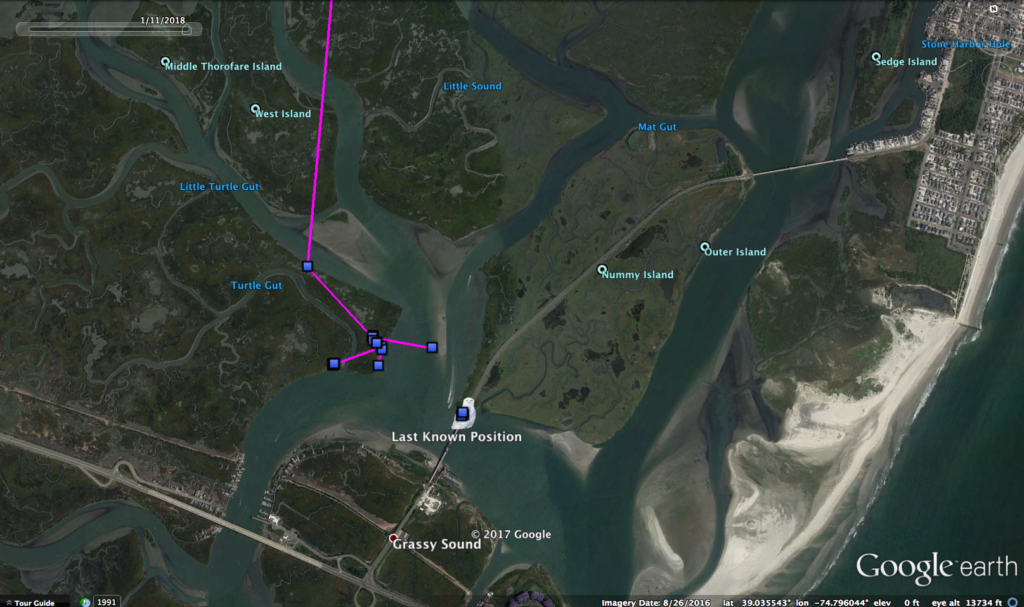

We became aware that something was wrong on Monday night, when Higbee’s transmitter sent its weekend data. It appears things were working fine through Jan. 4, the day an immense coastal storm slammed New Jersey, after which the transmitter recorded only a handful of GPS locations. All of them were along the ramp to the Grassy Sound Bridge on Ocean Drive, on a busy road connecting Wildwood and Stone Harbor, just north of Cape May.

Mike Lanzone from CTT and his wife, Dr. Trish Miller — both of whom had tagged Higbee on Dec. 5 — headed out immediately to check, but found an enormous mess in the wake of the blizzard, which dumped 18 inches (46 cm) of snow on the area, coupled with winds in excess of 50 mph (80 kph) that created a whiteout and drifted snow six feet (1.8 m) deep in places. Worse, the storm hit during a full-moon high tide that was 5.5 feet (1.7 m) above normal. Higbee apparently tried to roost in the back marshes north of Grassy Sound, but high, wind-driven waves were swamping the tidal marsh. Possibly to get out of those conditions, he flew toward Nummy Island near Stone Harbor. Crossing Ocean Drive, it seems he was hit by either a car or a snow plow — though, given the conditions, it’s possible the driver never even realized it.

Ice, snow and smashed remains of marsh grass (mixed with thousands of dead fish, as well as ducks and shorebirds) in the wake of the storm. (©Mike Lanzone)

When Mike and Trish arrived on the scene Tuesday morning, it was clear that finding Higbee was going to be hard. It was bad enough that plows had piled up masses of snow along the roadside where Higbee’s signal was coming from, but immense, storm-spawned waves had piled up ice floes and tons of marsh vegetation against the eastern end of the channel, then froze it solid.

Cedar trees, twisted and jammed together in the area where Higbee was lost, attest to the power of the storm. (©Mike Lanzone)

Mike and Trish returned with a metal detector, thinking it might ping off the owl’s metal leg band and give a better sense of where to look, but the thick snow, ice and junk defeated them. Still, Higbee’s transmitter was working — not getting great GPS points from the overhead satellites because it was buried, but sending sporadic data, and capable of receiving new commands. CTT sent it instructions to try to acquire more precise 3D locations, which the biologists could average to more accurately pinpoint where to dig.

It was a risk; if it was indeed buried, the unit was getting no solar recharge, and the new program would drain the battery much more quickly. But as the weather had started warming dramatically in recent days, everyone realized there was a rapidly increasing chance the ice would break up, and Higbee would sink or float away.

Armed with a more exact search area on Thursday, CTT pulled out all the stops. Essentially everyone in the office — programmers, biologists, administrative personnel — joined the effort, along with some of Cape May’s birding community. “We stopped at Lowe’s and got a bunch of pitchforks and rakes,” Mike said. Then they concentrated on an area about 13 feet (4 m) in diameter, which encompassed the latest and presumably more precise location data.

Higbee’s final data shows how he moved from the back bay marshes, flooded by the extreme high tide, to the the busy bridge crossing at Nummy Island. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

“We just started scraping, scraping, scraping, going down layer by layer,” Mike said, like an archaeological expedition. As they dug, they found countless dead mummichogs, a common tidal marsh species also known as killifish. “I think every time a wave came through they were washed up and frozen in,” Mike said. They also uncovered dead ducks and shorebirds, all left by the ferocity of the storm.

“Finally Andy McGann yelled, ‘I think it’s here!’,” Mike said. Higbee was about two feet down and more or less frozen in a solid block of ice. It quickly became apparent that he’d been struck by a vehicle, with a lot of damage to his right wing, although our wildlife pathology team will conduct a full necropsy. Mike said that the bird appeared to be in good physical condition at the time of his death, though, with body weight and muscle mass comparable to when he’d been tagged. “He’d been eating well, that’s for sure,” Mike said. Almost all of Higbee’s hunting took place in nearby tidal marshes that had been restored by The Nature Conservancy in New Jersey, working with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and other partners. The Nature Conservancy had generously underwritten the cost of Higbee’s transmitter.

Patty Doerr, director of marine projects for TNC in New Jersey, said, “We are deeply saddened that Higbee did not survive. During his short time as a science ambassador, he showed us in no uncertain terms how valuable New Jersey’s salt marshes are to snowy owls as a species. Having this insight only intensifies The Nature Conservancy’s commitment to continue working to make our state’s salt marshes as healthy and resilient as possible.”

Sadly, Higbee may not be the only victim of that stretch of Ocean Drive, which carries lots of fast traffic through the middle of prime wetland habitat. At least three other snowies were hunting the same area while the search team looked for Higbee, Mike said.

“While we were working, we saw an owl hunting, flying right at the road just two feet off the snow,” Mike said. “It was just about to cross the road, right in front of three cars, when it saw them and pulled straight up in the air. Clay Sutton” — one of Cape May’s premiere raptor experts — “said he’d seen the same thing happen twice in just the previous few days.”

This obviously was not the ending we were hoping for. But just as the loss of York last month in Maine provided stark evidence of the risk to large raptors from electrocution, Higbee’s death is a reminder of the many other dangers that snowy owls face when they leave the Arctic. Over the years, we’ve lost owls to plane strikes and jet-engine blasts, to collisions with electrical lines and electrocution, and to less obvious causes, like the owl that died for unknown reasons at an open-pit gold mine. We’ve never had a confirmed vehicle death, but we’ve also had owls simply disappear, their fates unknown — and a collision that destroys the transmitter leaves us with no way to find and recover the owl. In this case, we got lucky. But vehicle collisions are a serious risk for snowies. Just yesterday, two snowy owls were found dead from cars along a road in Wisconsin, just a short distance from where our newest owl Arlington hunts.

It’s a dangerous world for wildlife. The fun and exciting part of Project SNOWstorm is tracking the movements of these amazing birds — but when one stops moving, and we confirm its death, that’s critical information as well, however painful. Nor will Higbee’s contributions end with his death. For example, we’ll be able to compare levels of environmental toxins like mercury in his system at the time of his death with his capture more than a month earlier, an important snapshot of how life down here affects these owls in more subtle ways.

CTT is checking out Higbee’s transmitter, to see if it was damaged in the collision and aftermath. If not, we will try to redeploy it on another New Jersey owl this winter — just as Oswego‘s transmitter from last year, recovered when she collided with power lines in Canada, is now on Sterling, presumably somewhere on the ice of Lake Huron out of cell range.

8 Comments on “Losing Higbee”

Those are sad news :( Good to learn that the CTT team was able to find him for a necropsy.

Have there been any attempts to lower speed limits through important wetlands- in any state? by any group? This would be a smart move as there is a stretch in OH as well that is listed as 55mph and every spring hundreds if not thousands of birds are killed as well as turtles and other wildlife…. seems there is an easy fix if anyone would lobby for this change…

Great point and a helpful suggestion. I wonder how we as citizens could get that started?

Pingback: Understanding the Nomadic Habits of Snowy Owls – Cool Green Science

Pingback: Owl Baiting (Again) | The Pathless Wood

Pingback: Snowy Owls Spotted in New Jersey | njHiking.com

Have the other two owls in the area been seen or transmitter data obtained since the storm?

This was a devastating loss for the Snowy Owl species, for Project Snowstorm, and particularly, for Mike and Trish! Many thanks for everyone who participated in the difficult search for Higbee.