Project SNOWstorm lost a good friend this autumn — someone without whom the project would never have gotten off the ground.

R. James Macaleer, 81, of West Chester, Pa., passed away Oct. 29 after a fight with cancer that, for a while, we thought he was winning. Jim was a remarkable man — a Navy fighter pilot who, with two friends from IBM, started a company in the 1960s that computerized hospital records. Shared Medical Systems went on to become a $1 billion business, and the largest employer in its home county.

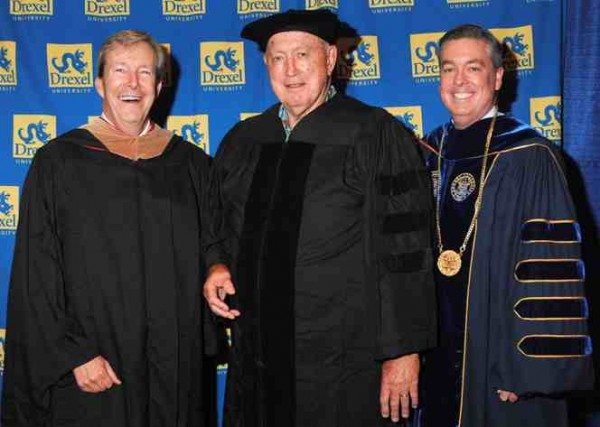

Academy of Natural Sciences president George Gephart (left) and Drexel University president John Fry (right) congratulate Jim Macaleer on his honorary doctorate in 2012. (Courtesy Drexel University)

But it was a passion for birds, science and conservation, which he shared with his wife Jean, that eventually led Jim’s path and mine to cross — though our first meeting was less than auspicious.

That was quite a number of years ago, in one of those slightly awkward donor meetings that working with a nonprofit sometimes requires.

As a board member of the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art (the institutional home for SNOWstorm), I’d gone along with our executive director to meet the Macaleers, whom a mutual friend had suggested we approach for funding. We asked for support for the center’s educational program; Jim and Jean listened politely, asked a few questions, but at the end of the meeting gently informed us that their giving priorities were set. Their longstanding commitments to the Boy Scouts, and his new role as chair of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, were taking up most of their philanthropic budget.

More than a year went by. One day I was appearing on an NPR radio program in Philadelphia, talking about the history of ornithology, and one listener with a deep, gruff voice –“Jim from West Chester” –called in to ask what I thought about a new technique using DNA instead of specimen skins to describe new species of birds.

I thought little of it until I was home, and an email from Jim popped up in my in-box. “Bet you didn’t know who ‘Jim from West Chester’ was, did you?” he asked. We chatted, and I invited Jim and Jean to meet me at our saw-whet owl banding station that weekend.

It was a great night — lots of owls, a large group of visiting school kids, and lots of excited energy. At one point, as I was heading out of the cabin to do a net-check, Jim followed me outside. “What would it take to really ramp up this operation?” he asked quietly.

That was the start of a long and very productive collaboration, with Jim and Jean’s family foundation supporting a fascinating range of research on saw-whet owl migration — using radio-telemetry, geolocators, radar and forward-looking infrared video, among other techniques we would never have been able to employ. When one rather expensive experiment appeared initially to fail, I told Jim it might have been less hassle just to flush their check down the toilet. “Welcome to the uncomfortable cutting edge of science,” he said with a wry smile — and renewed his support.

Periodically, I’d visit Jim at their home to give him an update on our saw-whet work. He’d usually suggest coming for lunch, and he’d always order hoagies so we could eat while we got caught up about owls and our shared enthusiasm for fly-fishing and birding.

In the first days of December 2013, the epic magnitude of the emerging snowy owl irruption that winter was becoming clear. Project SNOWstorm was coming to chaotic life, and we had a chance to quickly deploy some GPS/GSM transmitters on owls. But we needed funds — because no one had foreseen the invasion, we had no budget.

I fired off a hasty email to Jim — not asking for money, since he and Jean had just made a very generous gift to the saw-whet program, but asking whether he could help in reaching out to potential funders. Could he recommend someone with an interest in bird research who might be willing to underwrite a couple of transmitters?

I still have his response, which was typical Jim Macaleer. “I suggest you talk to Jean Macaleer,” he wrote. “She always seems to have a lot of money, particularly when she is out stimulating the economy. Until you get to talk to her, I’ll loan you money; if she is OK with it, we’ll convert it to a donation. Do you want to pick up the check tonight, or shall I mail it to you? I could leave it in the mailbox by our garage.”

And with that, Project SNOWstorm was off and running. Two weeks later we tagged Assateague, the first of 36 snowy owls (and counting) that we’ve fitted with transmitters.

Assateague, the first owl Project SNOWstorm tagged in 2013. (©Bob Fogg)

(Another good friend, also now gone much too soon, was equally generous in those early days, but that person requested anonymity and I’ll continue to honor that request. But we’re deeply grateful to him and his wife as well.)

Jim followed what we were doing closely, and I got regular emails from him asking questions and making suggestions. He and Jean were, I’d like to think, tickled to see how their seed money grew rapidly into this large and ongoing effort.

Unfortunately, Jim’s health took a serious turn for the worse around the same time. At first the aggressive treatment regimen he undertook seemed to have helped, but this past summer the cancer came back, hard.

I saw Jim a few weeks before his death, when he was still well enough for visitors, and as usual he peppered me with questions about owls — of many species, because he and Jean had quietly supported a number of other owl research projects around the country. It was hard to see such a strong, vital man reduced by illness, but I was grateful for the chance to tell him, again, how much of a difference he had made for so many people, and so many species.

On Nov. 22, there was a celebration of life service for Jim, and by my estimate more than 700 people jammed the ballroom of a hotel outside Philadelphia to pay tribute to him. There were stories of his days as a varsity wrestler at Princeton, his naval flight training in Pensacola, about his business acumen (and management style, leavened by his sharp sense of humor), his quick wit even when meeting presidents — and perhaps most of all, indications of Jim and Jean’s remarkable philanthropy, which ran a wide gamut from the Scouts to land trusts to science and bird conservation, to less public and more personal examples of their warmth and generosity.

All of us at Project SNOWstorm are grateful for Jim and Jean’s initial faith in what we’re doing — and while we miss him, we hope this continuing success of this project serves as one small monument to Jim Macaleer’s vision and love for birds.

6 Comments on “Farewell to a Friend”

What a beautiful and heartfelt tribute to Jim and Jean, Scott. It’s rare that an organization takes the time to acknowledge in such a loving and personal way the direct connection between a worthy project and the donors who took a chance in supporting it when it was still unproven. Thanks for a wonderful portrait of two of the people who’ve made Project SNOWstorm possible.

Condolences to all ♡

You all have my sympathies.

Oh, no, I’m so sorry.

Sorry to hear of his passing. My sympathies to his family and friends.

What a beautiful soul. His life sounds like a life of few regrets and major impacts…may he reap his rewards. Belated condolences to his loved ones, family and all who were touched by his being.