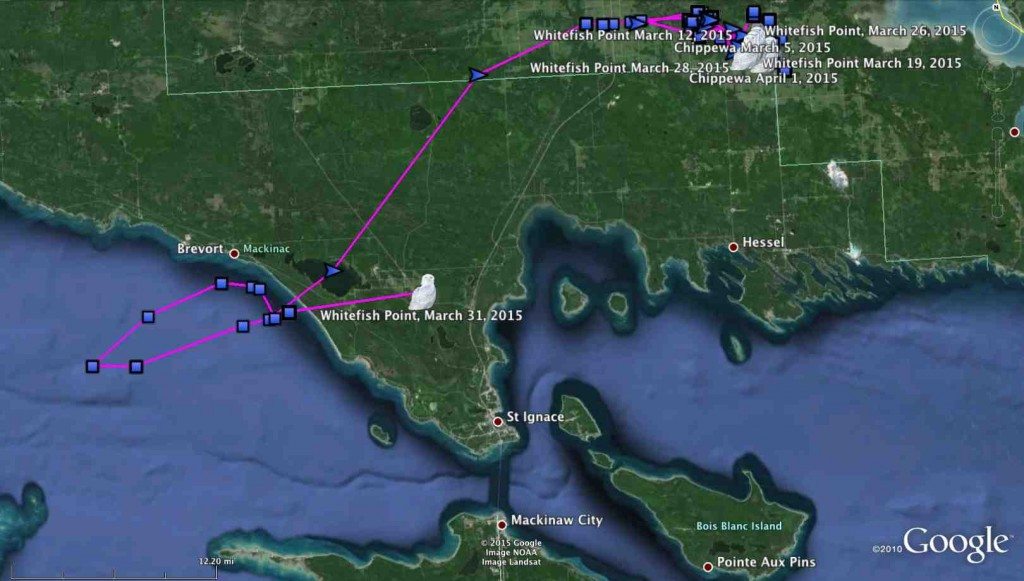

Whitefish Point finally leaves her winter home, while Chippewa stays put — for now. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The latest round of check-ins show that more and more of the tagged snowies are getting the itch to move — some in quite dramatic ways.

For instance, Whitefish Point, who has rarely moved more than one section road from her winter territory on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan this winter, took a long ramble on March 31, flying about 40 miles (66 km) out onto the still-frozen surface of Lake Michigan, just west of the Straits of Mackinaw.

It was a quick visit, and she came back onshore to a small area of farm fields about nine miles (14.5 km) north of St. Ignace, but when she transmitted Tuesday night she hadn’t gone back to her old territory.

(Meanwhile, her neighbor Chippewa stayed put — and it will be interesting to see if Chippewa starts nosing into Whitefish Point’s now-vacant territory, assuming the latter remains away.)

A couple of other snowies were right where they’ve been all winter — Orleans in New York, Millcreek in Toronto, and Braddock and Century in the St. Lawrence Valley.

Those characteristic, evenly spaced squares show how Buckeye has been riding Saginaw Bay’s slowly moving ice sheet in recent days. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

As the ice on Saginaw Bay in Lake Huron breaks up under the influence of sunshine and wind, Buckeye has been riding the giant ice sheets, as you can see in this screenshot of her tracks. What’s interesting is that the upper path took place on the afternoon and overnight of March 28-29, when the winds were from the southwest — the ice (and the owl) were moving from lower left to upper right.

Each square represents a stationary location, at 30-minute intervals — which means the ice Buckeye was riding was barely moving — easing along at just a quarter-mile an hour (.4 km/hour).

Then the winds shifted, and the lower track, ending in the icon for March 31, shows how Buckeye was riding the ice back to the southwest, under the influence of a northeasterly wind. The breeze must have been a wee bit stronger that day, because the ice was clocking along at a third of a mile an hour this time (.6 km/hour).

(There are multiple owl icons because we had a bunch of checks over the past few days. We’ve reset most of the transmitters to call home every three days, instead of weekly, so there’s less chance we miss an owl as it moves north of the cell network — plus the units are programmed to transmit on the first of the month regardless.)

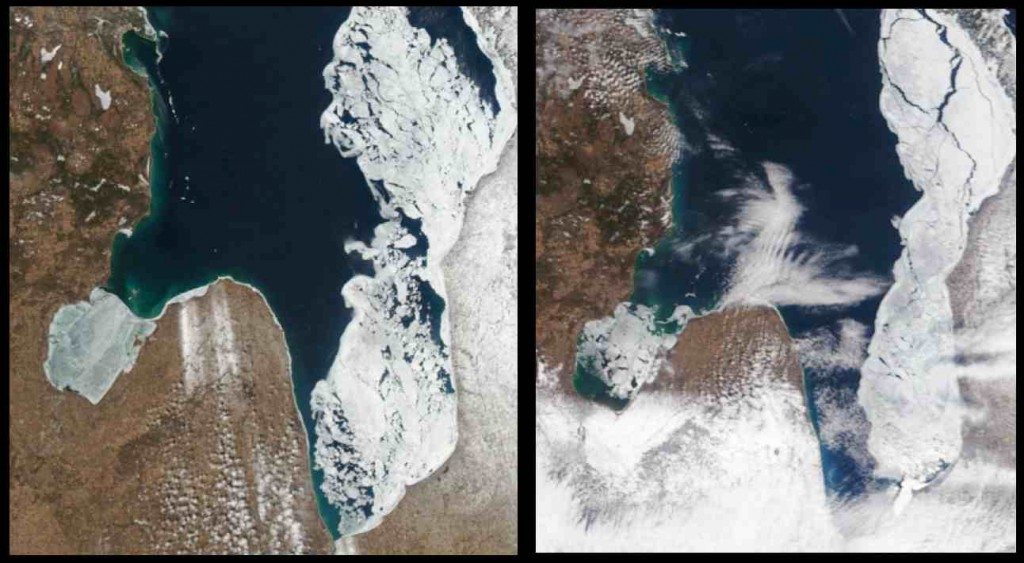

Comparison of ice on Lake Huron on March 28 (left) when the wind was from the northeast, and March 31, when it was southerly, pushing the ice out of Saginaw Bay, the “thumb” on the left. (MODIS imagery from NOAA CoastWatch)

The daily satellite images from NOAA show how dramatically the ice is starting to break up on Saginaw Bay. That’s still a lot of white, seen from high in space, but Buckeye’s days of ice riding are numbered, at least in Saginaw Bay.

The big traveler this time, though, was Geneseo, who hadn’t checked in last week. We assumed he was out of range on Lake Huron, where he’d been riding ice on March 19 when he last phoned home.

Composite image showing Geneseo’s movements on Lake Erie ice. Some of the positions along the north shore that appear to be in open water reflect the southerly shift of ice between late March and April 1, when this satellite photo was taken. (©Project SNOWstorm, Google Earth and NOAA CoastWatch)

Right idea, wrong lake. Turns out he’d flown back south the night of March 27-28 to Lake Erie, and had been out on the ice there — first south of Port Stanley, then flying farther east to Long Point, the world-famous migration hotspot, and home to Bird Studies Canada.

Although north winds had pushed a lot of Lake Erie’s ice away from the north shore, and much of it has melted in the western side of the basin, things are still pretty solidly frozen around Long Point — but with enough open-water areas to attract migrating waterfowl, and to support a hungry owl.

One Comment on “From Great Lake to Great Lake”

It is so interesting to follow these SNOWs. It will be interesting to see when Buckeye takes a bigger flight towards the North!