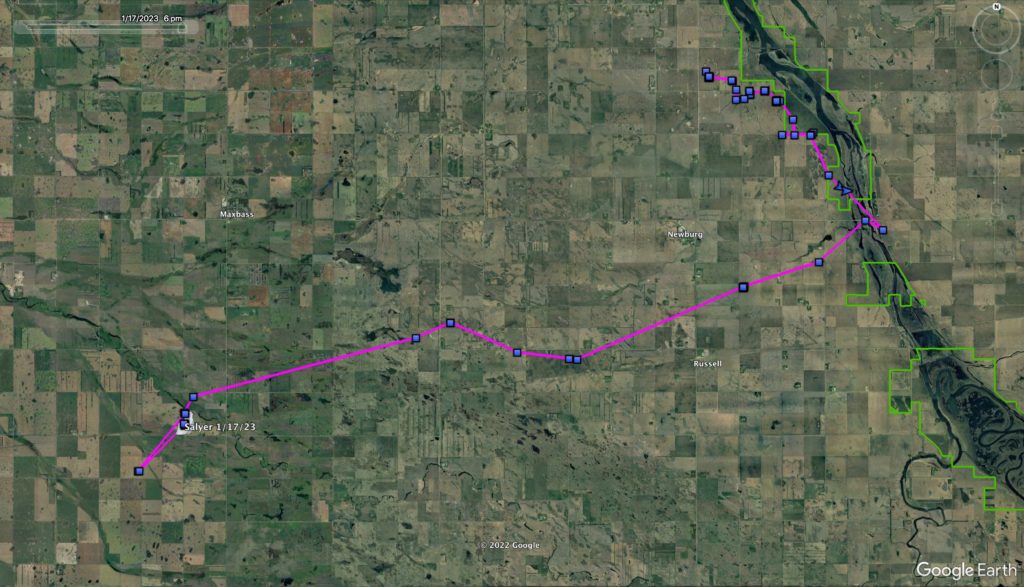

Salyer was trapped close to the J. Clark Salyer National Wildlife Refuge (in green), along northern North Dakota’s Mouse River. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Our banding teams have been making up for lost time recently, and that includes our longtime colleague Matt Solensky, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Prairie Research Center in North Dakota, who in his spare time traps and bands snowy owls for Project SNOWstorm.

As we’d noted in past blogs, Matt’s been out on the prairies a lot this winter, but the owls have been fairly thin in eastern North Dakota where he lives. But he recently heard from Larry Larsen, an avid birder who keeps tabs on snowy owls up in Bottineau County, along the Canadian border, and based on some intel from Larry, Matt headed back up there on lucky Friday, Jan. 13. Even before checking into his hotel, Matt headed out to where the owls had been reported.

“It didn’t take long to find the first one, which compared to the rest of this season was quite a relief,” Matt said. He set two traps, a bal-chatri noose trap and a bow net, each baited with a pigeon safely ensconced in a small cage for its safety.

“The very light owl made a rather timid approach on the bait after about 10 minutes,” Matt reported. “He spent the next 40 minutes dancing around and doing everything he could but be aggressive and get caught. Eventually, a couple of ravens arrived on the scene and that spooked him off. I had a moment where I thought I was going to have a raven in the bow net, but no such luck. Though he was timid, he was so interested in the bait I figured I’d try again first thing Saturday morning.”

Salyer is a third-year male, probably not quite old enough to breed. (©Matt Solensky)

Matt was back at that same spot before sunrise the next morning. “Just as it was getting light I saw what appeared to be the same bird sitting on the same power pole. I set the bait out and the exact same thing happened, only this time quicker. Owl: timid approach, not caught. Ravens: fly by and scare off owl. Owl gone.”

Disappointed but determined, Matt headed west along Highway 5 to another area where eBird has shown recent owl sightings. At first it was discouraging; there were high utility poles for owl perches, but between deep snow, lots of ravens and a lack of side roads for vehicle access, there wasn’t much opportunity.

“I didn’t see another owl until I got to where the [utility] poles turn south and run parallel to a gravel road for about ten miles. Also in this area is the Salyer National Wildlife Refuge with the Mouse River running through it. It’s not much of a river, more of a cattail slough, but great habitat for ring-necked pheasants, sharp-tailed grouse and partridge, among other owl-attracting prey,” Matt said.

A few miles south of the highway, Matt spotted a snowy. “He was on the top of one of the power poles and actually flew closer to me as I set out the traps. It was less than two minutes after getting the bait out that he made his first pass. As with the earlier bird it was a bit timid, but he quickly got to the caged bird in the bow net and I had him.”

Once he had the owl in hand, Matt called his colleague Tammy Otto, a biologist with the National Science Foundation’s National Ecological Observatory Network, to drive up and help him fit the bird with a transmitter — very much a two-person job. The owl was a third-year male, which Matt nicknamed Salyer for the refuge. (Which, in turn, is named for J. Clark Salyer II, the revered first director of the U.S. National Wildlife Refuge system.) Matt and Tammy had Salyer banded, processed and fitted with his transmitter by 7 p.m., releasing him into the darkness.

The next day the two went back to the same area to try for another snowy, despite freezing mist and fog. They spotted three birds, one heavily marked and two very white. “We tried for all three at times, but were hamstrung by ravens each time. I’m not sure any of the three ever saw bait as they were either really far away or were spooked off by the ravens very quickly. Pretty frustrating.” That’s often the way snowy owl field work goes — moments of easy exhilaration and long stretches of frustration.

Salyer’s transmitter was made possible by donations from the public to Project SNOWstorm, and as always, you can follow his movements on his tracking map.

6 Comments on “Introducing Salyer”

Slayer’ Love it. Love him.

I have a question. When you look at the map, what do the different colors of the dots mean…black, gray, yellow? Thanks.

Check out the inset box labeled “Device Track” — there’s a graded color bar from black to yellow showing that black is night, gray is dusk/dawn, and yellow is daytime.

Fascinating. Thank you for your important work.

I haven’t heard of any snowy owls down here in central New York this year. I am hoping they pay us a visit as the have in previous years. Do you we will be blessed with their presence?

Hard to say, but it’s been a very poor winter for snowy sightings in most of the Northeast. Perhaps the incoming blast of extremely cold weather will chase a few more south.