Sporting a prototype GPS/GSM transmitter, Assateague comes in for a landing in December, 2013 — the first owl that Project SNOWstorm tracked. (©Bob Fogg)

Three years ago this past weekend, Project SNOWstorm began in earnest. On Dec. 17, 2013, on the coast of Maryland, we tagged a young male snowy owl we called Assateague, named for the barrier island on which we trapped and released him.

The small group of us who watched Assateague fly off into the darkness that night with our first GPS/GSM transmitter on his back had no idea how rapidly SNOWstorm would grow, and that three short years later we would have accomplished so much.

We’re pushing ahead, and if we have the support, we plan to tag at least 10 more owls this winter, focusing on specific habitats and regions where we need a better sample. But as we mark both our third anniversary and the start of our new field season, we thought we’d take a look back over the next couple of days at what Project SNOWstorm been able to do — all of it with your help, since everything we do is underwritten entirely by donations from the public. Our successes are your successes.

BY THE NUMBERS: Since that first owl in 2013, we’ve tagged a total of 43 snowy owls in 10 states, as far west as North Dakota, north to Maine and south to Maryland. We’ve tracked those owls across more than 50,000 miles (80,500 km) of total distance, while collecting more than 160,000 incredibly precise, three-dimensional GPS fixes that provide latitude, longitude, altitude and flight speed. In some cases, we’ve collected such data at intervals of just 30 seconds.

In all, this represents by far the most detailed movement data set for this species — and likely for any owl — ever collected. In terms of both the number of tagged birds and the size of our data set, SNOWstorm has quickly grown into the largest snowy owl telemetry project in the world, and we’re just starting to crack open the wealth of information hidden in those data.

Tom McDonald releases a young male snowy owl, captured Dec. 16 just west of Rochester, NY.This bird isn’t tagged, but we plan to put transmitters on 10 more snowies this winter. (©Aaron Winters)

WHO WE ARE: Project SNOWstorm now counts more than 40 scientists, banders, wildlife veterinarians, pathologists and other specialists as members of its core team, including some of the most experienced snowy owl and raptor experts in North America:

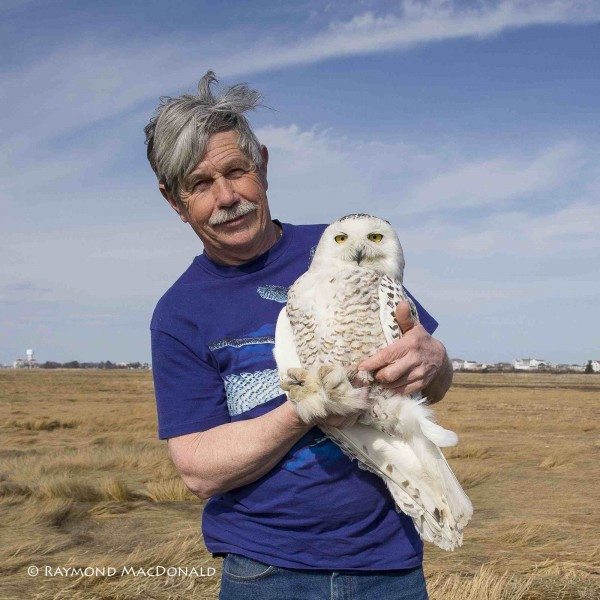

Norman Smith, the director of the Blue Hills Trailside Museum in Milton, Mass., and one of the most experienced snowy owl researchers in the world, was a co-founder of Project SNOWstorm. (©Raymond MacDonald)

—Norman Smith from Massachusetts Audubon, who has been studying snowy owls at Logan Airport in Boston since 1981.

—Tom McDonald of Rochester, NY, who has been banding snowy owls in upstate New York and around Lake Ontario for more than 25 years.

—Dr. Jean-François Therrien from Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania, who with his colleagues at Laval University in Montreal studies snowy owls on Bylot Island in the Canadian Arctic.

—Dr. Tricia Miller of West Virginia University, who is applying her expertise in studying the migration of eastern golden eagles to the movements of snowy owls.

—Dr. Eugene Potapov of Bryn Aythn College, who studied snowy owls for years in Siberia, and co-authored the authoritative monograph The Snowy Owl.

—David F. Brinker of Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the founder of Project Owlnet and one of the prime movers behind SNOWstorm.

–Eagle biologist Michael Lanzone and his colleagues at Cellular Tracking Technology, who continue to provide the transmitters we use at their own cost, a savings that now exceeds $80,000.

Tomorrow, we’ll share some of the important discoveries we’ve made over the past three years, and how we’re disseminating that information to the public and to conservation professionals. In the meantime, if you’d like to help Project SNOWstorm, it’s easy and tax-deductible.