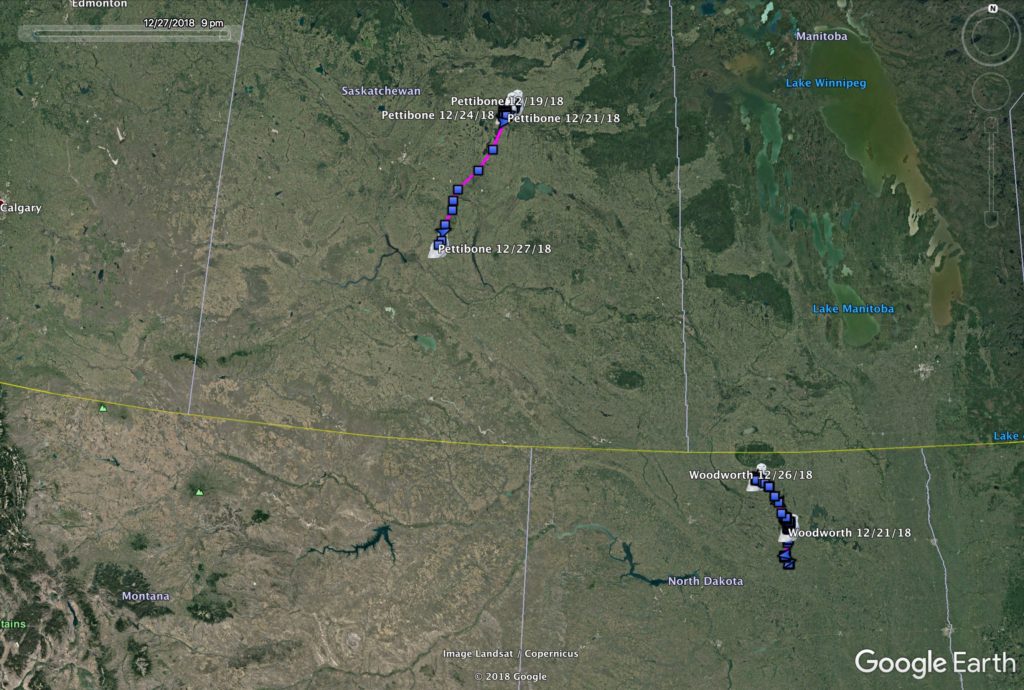

Two owls, opposite directions, both heading for the border. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

I often tell groups to whom I’m speaking about Project SNOWstorm that virtually every one of the owls we’ve tagged has surprised us in some fashion. And that’s certainly the case now, as we watch two owls in the same general region heading in opposite directions.

After more than a month and a half near Melfort in central Saskatchewan, Pettibone began moving south again in the wee hours of Dec. 27. Moving at about 36-41 mph (59-66 kph) he pushed down through the prairies mostly under cover of darkness, so that by the next evening he was about 120 km (75 mi.) northwest of Regina, SK, midway between Regina and Saskatoon and not far from the town of Davidson. Like much of Saskatchewan, this is a landscape of massive grain fields, freckled with glacial pothole ponds and marshes. This is the same area Stella passed through on her way south last month, heading toward the Montana border.

At the same time that Pettibone was heading south, Woodworth over in North Dakota was flying the other way. An adult male like Pettibone, this owl has been moving almost from the time he was tagged in early December. His habit has been to settle in for a day, sometimes two, then move at night, steadily traveling north and northwest. Like Pettibone, his flight speed is about 40 mph (68 kph) when he’s moving — which is, interestingly, close to the normal, traveling flight speed for a wide variety of birds, from songbirds to large raptors.

By midday on Dec. 26, Woodworth had flown more than 120 miles (191 km) in straight-line distance, although his transmitter shows he actually covered 190 miles (305 km) as he moved up through Benson and Pierce counties to his last location, on the line between Rolette and Bottineau counties.

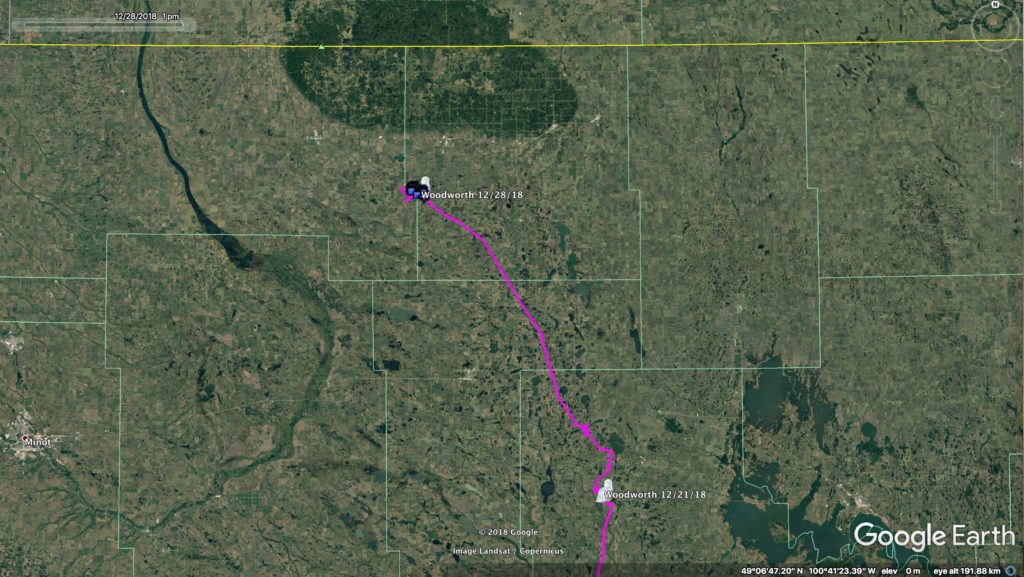

Woodworth is just south of Turtle Mountain, a wooded plateau in a sea of prairie, bisected by the international border. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Woodworth is just a few miles south of Turtle Mountain, a plateau rising a several hundred feet above the surrounding plains, and dominated by hardwood forests — an oblong island or woodland in a sea of grassland and ag fields. The U.S.-Canadian border slices through the middle, with the International Peace Garden in one corner, and the Turtle Mountain Reservation on the southeastern edge. Woodworth is also less than 20 miles (32 km) from Clark Salyer National Wildlife Refuge, a huge tract along the Souris River.

Why are two adult male owls flying in opposite directions at the same time of year? That question we can’t answer, but my suspicion is it may have to do with prey densities and perhaps snow cover. A lot of raptors initially shift around, looking for a place with lots of food — though in the case of small mammals like voles, once there’s a deep snow cover it can become hard to hunt. Snowies, though, are incredibly adaptable hunters — they’ll take mice and voles, muskrats, ducks and geese, rabbits and hares, large songbirds, grouse (like ptarmigan) or pheasants — whatever the local buffet provides. But it may also simply be a case of individualism — something else we’ve seen over and over is that no two owls are the same.

Will they converge on the U.S.-Canadian border? Only time will tell, but keep an ear to the ground for more updates.

One Comment on “Heading for the Line”

Maybe they’ll meet by the new year!!!

Thanks for the updates.