All three of the juvenile snowies we tagged this past summer in Alaska have moved far from their banding site, but remain in the Arctic. (©Project SNOWstorm)

As regular followers of Project SNOWstorm know, we did something this past summer that no one has ever done before — tagged juvenile snowy owls in the nest with satellite tags, so we can see where young birds go in their first winter. SNOWstorm team member Jean-François Therrien from Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, who tagged the trio in Alaska, has this update.

* * * * *

There’s exciting news from the North as we continue to track the movements of three young snowy owls, from their nest site in northern Alaska through their first year of life, in cooperation with our colleagues at the Owl Research Institute.

Earlier this fall, we had seen that two of the three chicks had started moving away from their birth (or natal) grounds at Utquigvik, formerly Barrow, Alaska. We’d been concerned that the third chick’s signal stayed in Utquigvik, suggesting it might have died. Now, though, we just received news that the third chick might also be on the move.

To track these owls moving across regions where the cell phone network is mostly nonexistent, we’ve had to rely on Argos satellite technology instead of the GSM cell phone network as we do with our standard transmitters. The units we are using on the chicks are much smaller than the one commonly used by Project SNOWstorm over the years, because we know the odds are already stacked against young birds. But because they carry no solar panel, with power coming only from a small internal battery, the transmitters record their location much less frequently than we do with GSM.

Not much bigger than a quarter, the battery-powered transmitters are programmed to collect data every five days for up to two years. (©JF Therrien)

We went a long way to save each micro-volt of battery power so the units could track the birds for a longer period — up to two years. So we programmed the units to record their location only once every five days, which is relatively infrequently but still sufficient to assess dispersal and survival rates, which is what primarily interests us. Only when the unit has collected at least three locations does it transmit that data to us via the Argos satellites. The rest of the time, the unit goes into sleep mode to save power. This means that in the best case scenario, we would receive an update every 15 days — but that doesn’t take into account all the other issues that could prevent the transmitter from connecting with the satellites at a given time. For instance, the bird could be in a valley or close to a building in Utquigvik that blocks the signal, or the orbiting satellites could be too low on the horizon at the time the transmitter turns on and tries to send data.

Despite those challenges, we chose this technology to answer very specific questions — primarily dispersal movements and juvenile survival rates — that wouldn’t be possible using GSM technology because as you move north of the boreal forest, the cell phone network is scanty at best. For each recorded location, the Argos system also provides a value of accuracy, which depends on the number of signals received and the time between them. In other words, it’s a check on how reliable is the location.

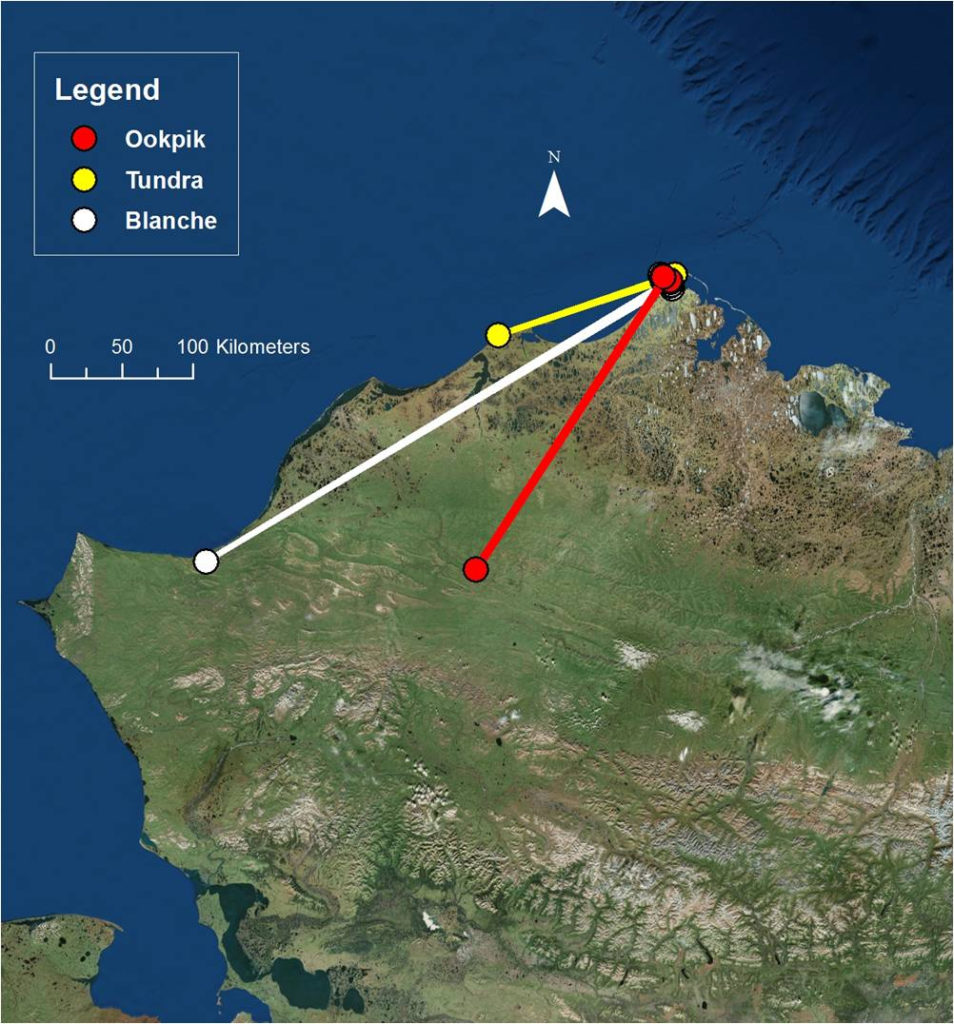

So in the latest update, the locations we received for Blanche, in the westernmost section of the Alaskan North Slope somewhere near Cape Beaufort, are of low accuracy, which mean the bird is “most likely” there – we need to keep in mind that there is a chance this is only a glitch, and we’ll have to wait and see! So this exciting result still needs to be taken with some caution at this point.

The other two birds (Ookpik and Tundra) have both made movements away from their natal grounds and in each case, the accuracy of the locations were high, so we are very confident these movements weren’t outliers. Tundra is near Wainwright on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, about 75 miles (122 km) southwest of Utquigvik, while Ookpik has moved far inland along Carbon Creek, a tributary of the Utukok River, about 160 miles (250 km) south-southwest of its nest site, and some 93 miles (150 km) from the ocean. This is the heart of the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska, a 23.5 million-acre tract that represents the largest area of undisturbed land in the U.S. (Unlike the GSM tags we use on adult owls, we don’t have regularly updated online maps for these three birds.)

We knew that tracking snowy owl chicks would come with some limitations, and at times a bit of frustration in our current world of “I want it here and now.” But reliable estimates of dispersal and survival will only come through careful scientific design and, in this case, patience! This is nonetheless very exciting.

* * * * *

Remember, Project SNOWstorm is funded entirely by small, tax-deductible donations from the public. You can learn more about our plans for this winter’s season, or make a contribution that will allow us to continue our ground-breaking work.

4 Comments on “Staying in the Arctic”

If these fledgling snowies survive, will you be able to find them to fit them with the tracker you use in adults? How will you remove the smaller trackers?

That’s the plan (and hope) but it depends on where they travel over the next two years while the batteries in the satellite units last. If they remain in the Arctic it would be logistically almost impossible — working in the Arctic, away from towns like Utqiagvik (Barrow), requires enormously expensive air transport. If they come south into more accessible areas, though, we’d love to swap out the battery sat units for solar GPS/GSM transmitters.

I should also have mentioned that removing the satellite transmitters is simply a matter of snipping off the woven Teflon ribbon backpack harness, then replacing it with a new one holding the GSM transmitter.

Pingback: A Sigh of Relief - Project SNOWstorm