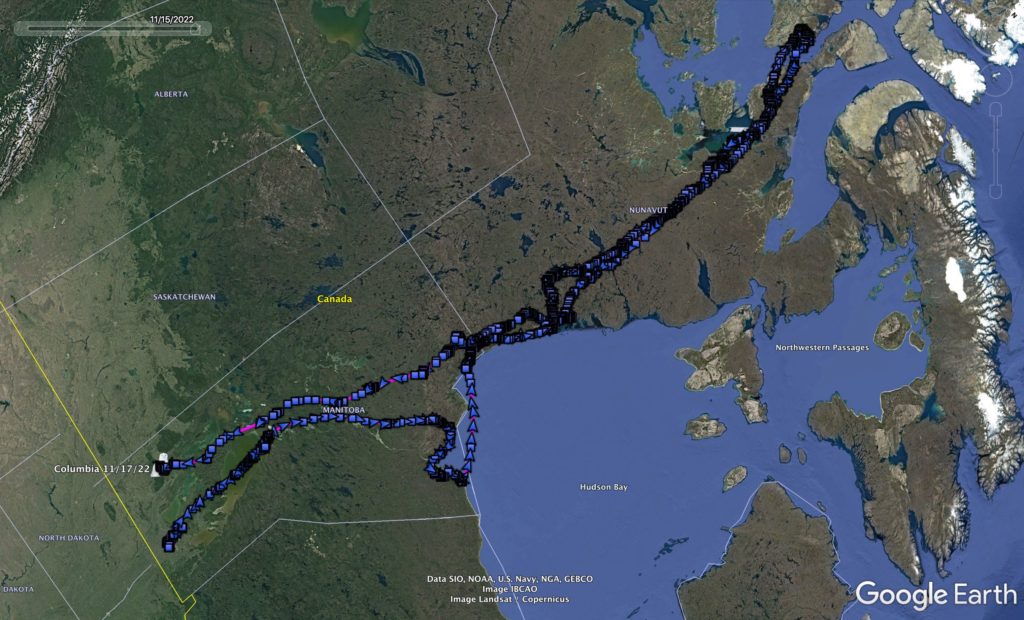

Columbia’s 2022 travels north to Prince of Wales Island in the Arctic and back south again this month. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Welcome back, everyone, to another season — our 10th — of snowy owl research here at Project SNOWstorm! We’re anticipating an interesting year, with some big developments both in the field and off that we’ll be sharing in the weeks ahead.

Columbia in 2020. (©Monica Hall)

But first, we have two treats. One is news of the first returning owl of the season — Columbia, an adult female originally tagged in Wisconsin in January 2020, who checked in Nov. 13 from southwestern Manitoba. Her data shows she spent the summer in the central Canadian Arctic — though it’s unclear whether or not she nested. Columbia spent most of the summer in a roughly 300-hectare (740-acre) area of Prince of Wales Island, but her location data doesn’t show the enormous number of stationary GPS fixes in one central spot that would clearly indicate the presence of a nest. It’s possible she started to nest and lost the clutch, or simply stuck to a small area because of abundant prey. You can explore her data and draw your own conclusions by checking out her tracking map.”

Also, every year we ask Dr. Jean-François Therrien of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania, one of SNOWstorm’s core leadership team, to bring us up to speed on how the summer breeding season went in the North American Arctic. J.F. did his Ph.D. at Laval University studying the nesting snowy owls of Bylot Island in the Canadian Arctic, where Laval has a long-term research site, and he’s in regular touch with scientists across the North. What kind of snowy owl flight might we expect this winter? Here’s J.F.’s 2022 report.

* * * * *

“Summer 2022 saw very low lemming abundances across most of the Canadian Arctic, the core breeding range for the snowy owl, including the long-term study site on Bylot Island (Nunavut). The only place harboring nesting snowy owls that we are aware of in 2022 was on Ward Hunt Island at the very northern tip of Canada (only a few hundred kilometers away from the North Pole).

Our colleagues in Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow, Alaska) with the Owl Research Institute reported only a single nest in 2022.

©Jean Hall

The last time snowy owls nested in abundance on the Bylot Island long-term study site was in 2021, when the last waves of the pandemic still prevented us from visiting the field station in the high Arctic. We were, however, excited to hear about a new technique being developed by our colleagues from Université Laval in Québec, Canada, to detect nesting snowy owls on the tundra — from space.

Using high-resolution satellite images from 2021, when owls were nesting on Bylot but the pandemic kept researchers away, they’re developing a tool that can detect a nesting snowy owl against the green and brown tundra remotely. The process starts with images that have a resolution measured mere centimeters, which are analyzed by an algorithm that can pick out white objects that are potential snowy owls. That’s then combined with ground-truthing the following year to confirm which of the white objects were artefacts like white rocks, and which ones were no longer present — those would have been nesting snowy owls. This allows our colleagues to estimate the abundance of owls on the study site even though no humans were present.

Given this past summer’s observations, we are not expecting a huge winter irruption at our latitudes this coming winter and we are eager to see if the situation will improve on the breeding grounds in 2023. We have been anxious for a productive breeding season (when there isn’t a pandemic) so we can deploy tiny satellite transmitters on juvenile snowy owls.

In the meantime, Dr. Rebecca McCabe here at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, part of the SNOWstorm team, is currently working with our colleagues in the International Snowy Owl Working Group on a worldwide population assessment for the snowy owl. (This effort is being partially funded by Project SNOWstorm through the donations of its many supporters.) The assessment will result in a comprehensive paper assessing for the first time the snowy owl’s global status, as concerns have recently arisen regarding its long-term conservation.”

14 Comments on “The First News From the North”

Welcome back Columbia. Hoping to see many more and would be thrilled to see Wells show up.

If anyone’s interested, I posted some screenshots of where Columbia spent most of her summer

on the community section of the Facebook page.

I’m not sure but I think one year there was no nesting seen at a place where they were doing a study witch was an indication of a poor season but for some reason we had an irruption and the explanation was that the snowy’s used a different nesting region then the usual one. Can’t recall exactly when but I think it was between the 2013-2018 seasons.

Thanks for the update.

You’re quite correct, Richard — people are thin on the land in much of the Arctic, and there are few areas where there are researchers on the ground to see what’s happening. So while we *think* this will be an off-year in terms of a large irruption of young snowies, we can’t be sure, and there may have been a lemming boom and big breeding event somewhere under the radar. And in the Great Lakes and East we can probably expect what’s sometimes called an “echo irruption” of surviving, second-year owls that migrated south for the first time in last year’s modest irruption. That unpredictability is always one of the exciting aspects of working with this species.

Hello

We were looking at the map of her path.. there are arrows and there are squares. What do the squares mean.. thank you

That kind of map is generated in Google Earth from the .kml file we download direct from the CTT server; the squares are stationary locations, the arrows are GPS fixes when the owl is moving. The maps we display on our website contain all of the same data, just in a different style. Each location is clickable and will show the date; time (UTC, Coordinated Universal Time, better known as Grennwich Mean Time); latitude and longitude; altitude (which could be ground level or in flight); and speed, if the owl was flying. These maps lack different icons for stationary and moving, but they do allow color-coding of the location dots to represent time: yellow for day, black for night, gray for twilight.

Thanks for the update Scott. Looking forward to hearing about the other snowies and what they’ve been up to.

Will there be more transmitter placements on any new owls this season?

Yes, we’ll be tagging additional snowies this winter. Matt Solensky, who had a slow winter last year in North Dakota, is hoping for a better season, and if we get some early-season owls in Acadia National Park in Maine we’re poised to try to tag one wintering in the alpine zone on Cadillac or Sargent Mountains. We also have two new (though deeply experienced) banders working with us in southern Ontario, Charlotte England and Malcolm Wilson, who completed their training this fall in fitting snowy owls with the backpack harness style we use, and are waiting on their final provincial permits.

It’s always great when the first owl ins the season arrives, welcome back Columbia!! Looking forward to some of the other snowies return, maybe this year Harsdcrabble will show up…!

Thanks Scott and J.F. Therrien for the updates.

This is honestly one of the most exciting research projects out there. I am so delighted to share this data with schools I work with.

Thank you to everyone involved. I am on my way to Winnipeg and I plan to share your amazing work with schools.

Snowy owl migration is just fascinating and the science behind this is making it come alive for so many.

Thanks Scott and J.F. Therrien for all the updates.

Just an FYI, we have always been happy to share our raw data with teachers who want to use it for school lessons – the only request, obviously, is that they not publish anything using it.

Hi Scott and all, as a high school ecology teacher in northern (lower peninsula) Michigan, this report is helpful and a teeny bit disappointing. So far, eBird has only one spotting in MI, so that in itself will be instructive. In my years of teaching, there is NOTHING like a snowy owl spotting to open students to the beauty and power and fragility to the more-than-human-world. Gratefully for all the work you do, ME and the life-science students at Interlochen Arts Academy

Awesome blog. My favorite insight: using high-resolution satellite images to detect a nesting snowy owl against the green and brown tundra. Wow. Incredible. Thank you. ❄️

I have to say, I think this could be a game-changer because right now we have no way of surveying snowy owl nesting activity across huge, largely unpopulated areas of the Arctic. But with AI and remote sensing it may finally be possible. We’ll keep our ear to ground on this emerging technology and update everyone as appropriate.

Snowy Owls have been seen on Wolfe Island, Ontario this month which is about the regular time we get them each winter.