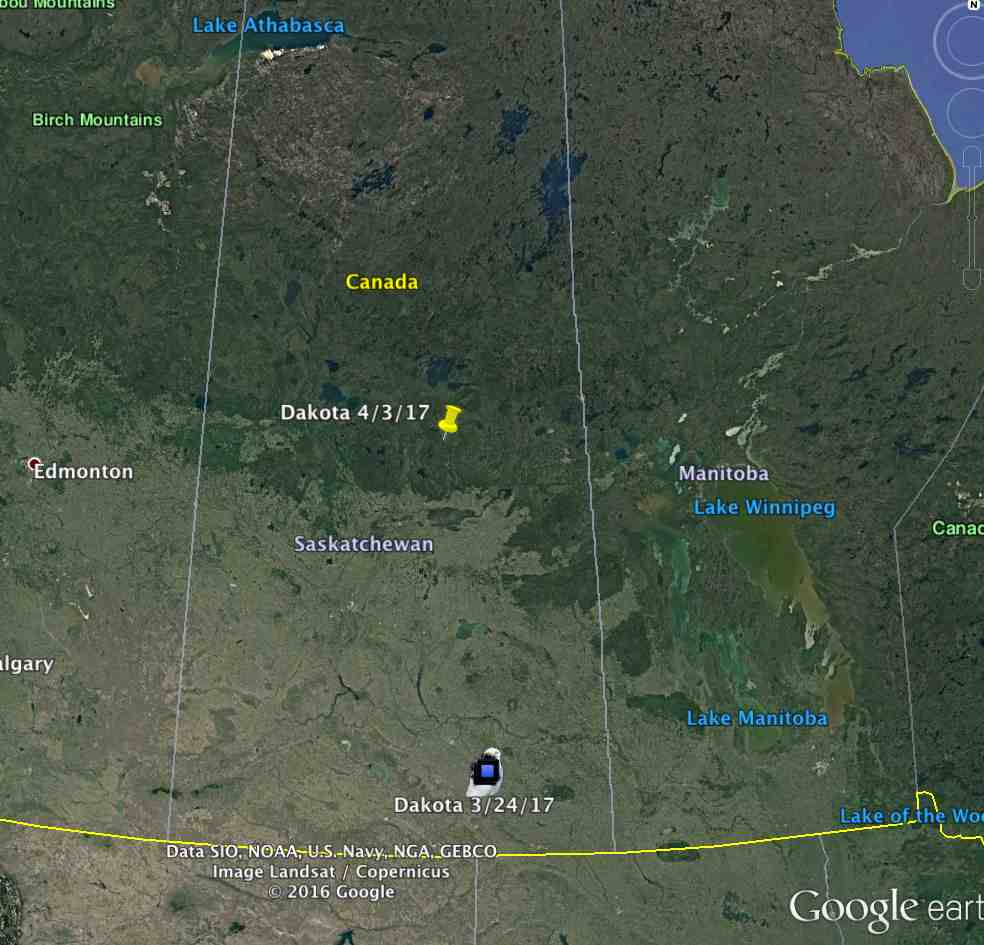

No wonder she was out of touch — Dakota’s been on the move, and is halfway north through Saskatchewan, close to the edge of the cell network. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Due to a glitch, this update scheduled for Tuesday April 4 didn’t post — sorry for the delay, and we’ll have a further update on the latest movements of the owls in another day or so.

The Project SNOWstorm team

———————

It’s definitely spring, and robins and geese aren’t the only birds making serious tracks to the north. After a quiet spell, there’s suddenly a whole lot going on with SNOWstorm’s tagged owls.

Dakota was missing in action last week, but yesterday morning at 4 a.m. I heard my phone buzzing, and when I groggily read the text, I found a CTT notification that her transmitter had checked in. No wonder she’d been off our radar — she was about 470 km (292 miles) north of her winter territory near Francis, Saskatchewan, and was in the dense boreal forest between Clarence-Steepbank Lake and Narrow Hills provincial parks of central Saskatchewan.

That’s also just about the end of the line for the cell tower network in that part of Canada, with a very sparse array of towers along a few of the major roads. It appears we got lucky that Dakota was near enough to send a bit of her data, but it must not have been a very good connection.

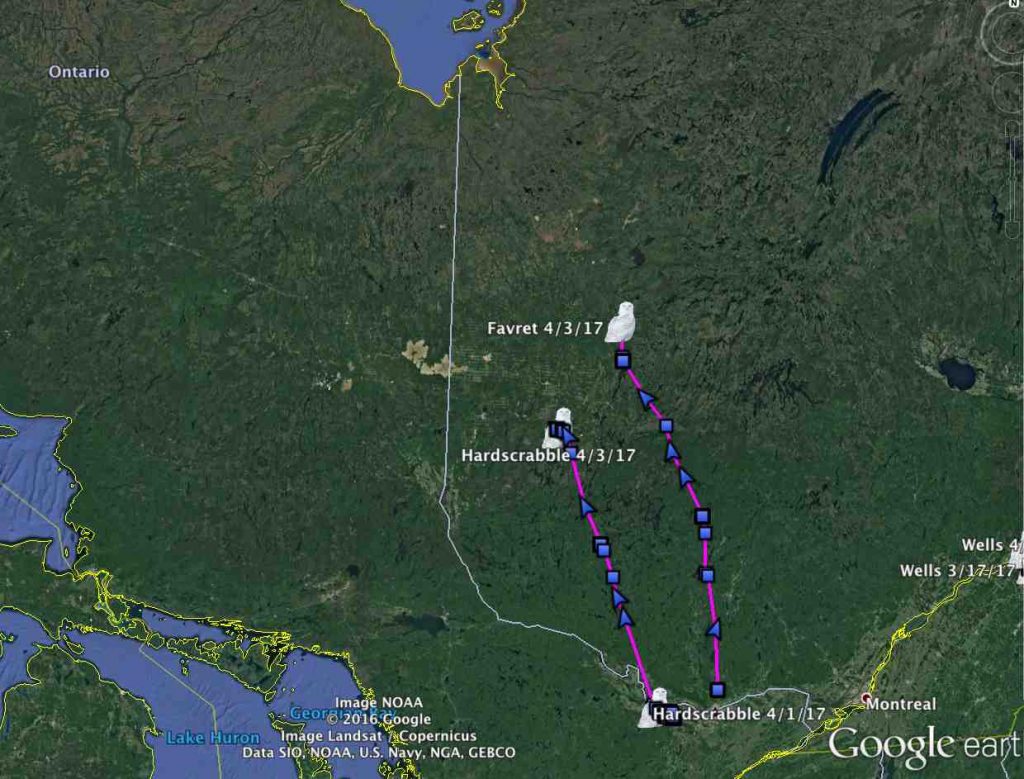

Last night the remainder of the owls were due to check in, and as the transmissions started coming in we learned that Hardscrabble and Favret — who had been in the Ottawa River valley — had also made significant flights north, into west-central Quebec.

Having left the Ottawa River valley within hours of each other, Hardscrabble and Favret both pushed hard through western Quebec over the weekend. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

In two days, Favret had traveled more than 400 km (250 miles) north and then northwest, across the immense Baskatong Reservoir in the Gatineau River valley, over Lac Parent, and at dusk Monday was 13 km (8 miles) from the town of Lebel-sur-Quévillon. This is industrial forest country — boreal spruce stands that are a patchwork of immense clearcuts, creating openings that a snowy owl would find attractive in an otherwise alien wooded landscape.

Interestingly, that’s very much the same track that Hardscrabble took north last year, even to passing through Lebel-sur-Quévillon (though not pausing for a rest). And speaking of Hardscrabble, he left his recent haunts near Arnprior, Ontario, within two hours of Favret’s departure Saturday night. He flew across La Vérendrye Wildlife Reserve, at 12,600 square km (4,864 square miles) the largest contiguous nature reserve in Quebec — a place of remarkable natural beauty. But for a snowy owl, looking for wide-open horizons, this forest of spruce and birch would appear hostile, and when Hardscrabble needed to put down for the day after his first night of flight, he did so at the edge of Lac Ward, one of hundreds of bodies of water in the reserve.

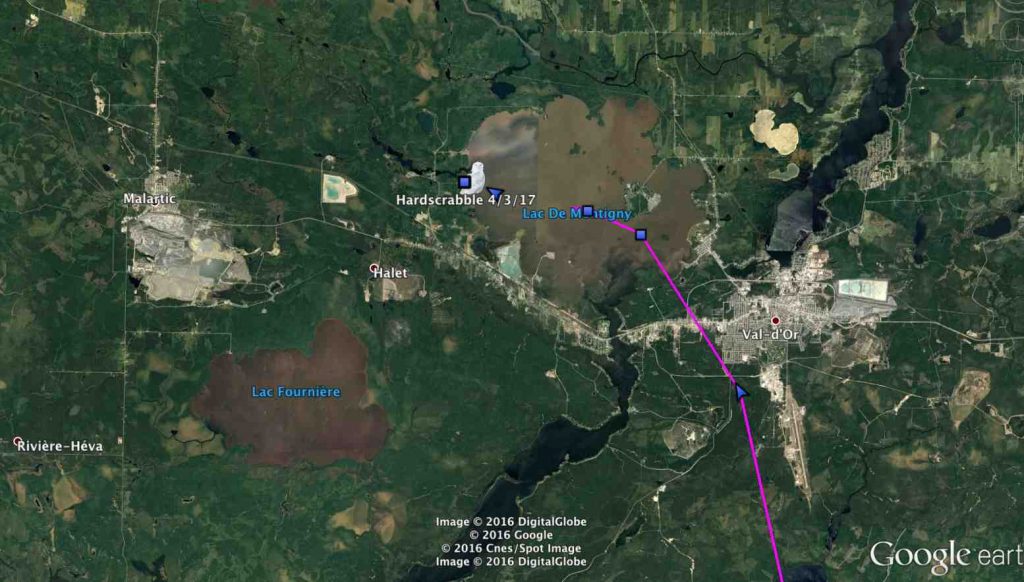

Turn north! We really, really don’t want Hardscrabble tempted by the open but dangerous spaces of the enormous gold mine at Malartic. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The next night he flew on, still taking a north-northwestern tack, and came down at Val-d’Or, “Valley of Gold,” a large mining town that sits in one of the richest gold-producing areas in Canada. At daybreak on Monday he was on the west shore of Lac de Montigny — a place that Baltimore had used for several day on his northbound migration in the spring of 2015. Hardscrabble was still there at dusk that evening when his transmitter sent its thrice-weekly data stream.

We hope he keeps moving north, because that part of Quebec has an unhappy association for those of us at Project SNOWstorm. Less than 10 km (6 miles) to Hardscrabble’s west is Malartic, home to the largest open-pit gold mine in Canada — an invitingly open, treeless area in an otherwise largely wooded environment, but one of the most dangerous places (short of a major airport) that a snowy owl is likely to wind up. In the spring of 2014 one of our first tagged owls, Oswegatchie, found himself at Malartic, and never made it out.

Oswegatchie’s signal disappeared for many weeks, and when his transmitter finally reconnected, it sent hundreds of stationary locations. With terrific cooperation from the mine’s officials, and help from Canadian scientists, his carcass was recovered, but it was bones and feathers, with no way to know whether he’d died from natural causes or something human-related. But we’ll all be happy if Hardscrabble detours around Malartic and keeps heading back to the Arctic.

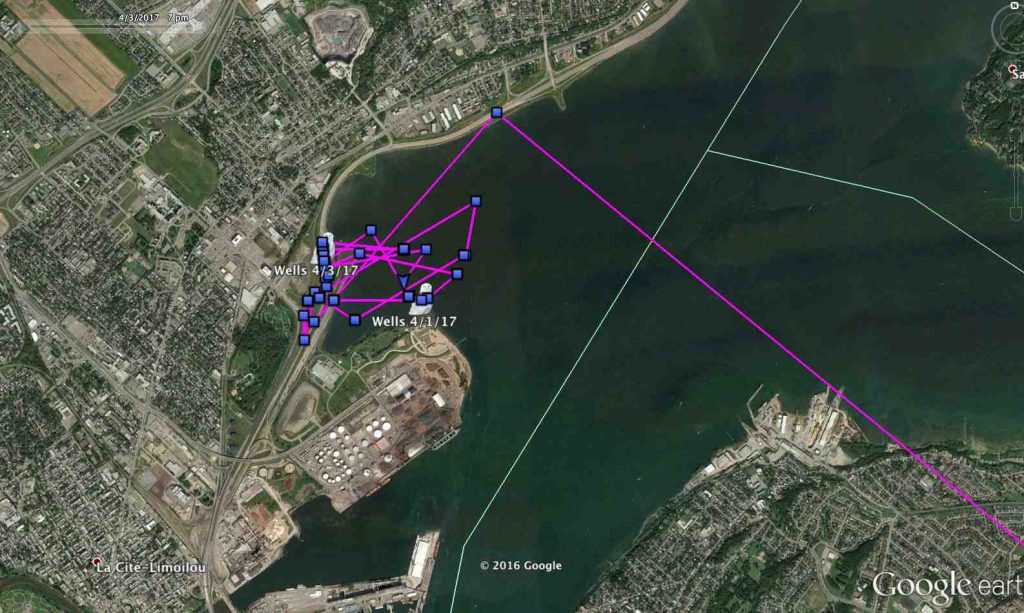

A cosmopolitan owl, Wells has been hunting the edge of the 27-hectare (67 acre) Domaine de Maizeret park in Quebec City. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Wells, who started north earlier than any other owl this year, leaving the coast of Maine back in late February, seems content for the moment to stay in and near Quebec City. The past couple of days she’s been using the Domaine de Maizerets, a nice little park on the waterfront of the St. Lawrence — and the street lamps along nearby Highway 440, which probably provide a great view of tasty waterfowl.

(Longtime SNOWstorm team member Jean-François Therrien at Hawk Mountain, who is from Quebec, was excited to see where Wells was hanging out — as J.F. told me over the weekend, he and his wife know that park well, and Cassandra even knows the Subway sandwich shop where Wells had been perching across the river in Desjardins.)

Only two tagged owls remain south of the U.S. border, that we know of (Oswego’s transmitter has gone silent again.) Chickatawbut remains on the New England coast, shifting back and forth between Hampton Beach, N.H., and Salisbury Beach, Mass., mostly patrolling the saltmarsh and tidal flats rather than hunting out over open water.

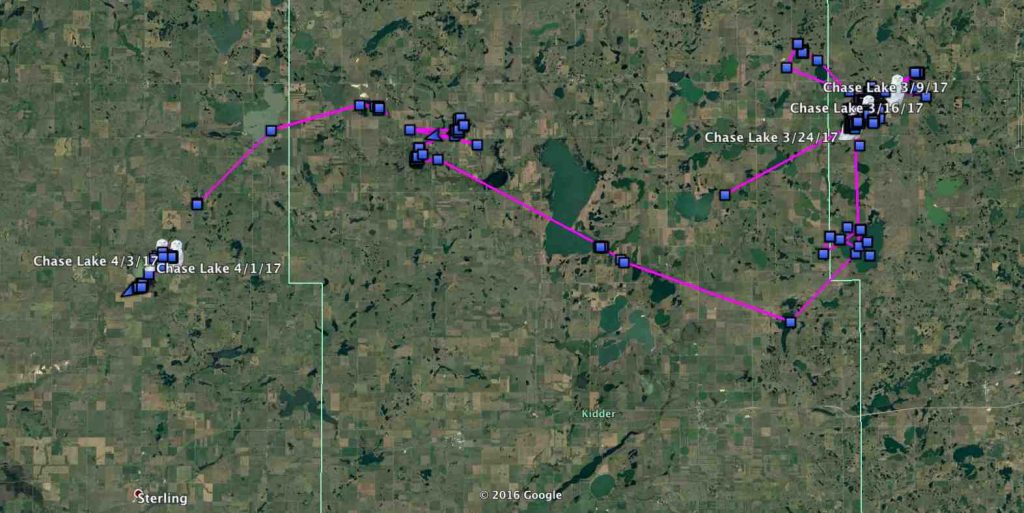

Chase Lake’s movements west over the past few weeks. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

And in North Dakota, Chase Lake has moved about 40 miles (65 km) west of the area where she spent most of the winter. Her latest hangout is Rice Lake in Burleigh County, about 11 miles (18 km) north of the town of Sterling.

Looks great to a snowy owl — a Google Earth Street View look (taken in autumn) of Rice Lake in Burleigh County, ND. The purple line is one of Chase Lake’s movement markers. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Why are these two hanging back, when the others are pushing hard for the north? It’s probably a question of age and priorities. Chickatawbut is a juvenile, in her first winter of life and likely a long way from being old enough to nest. Chase Lake is a bit older — based on her wing molt when she was tagged, she was born in the summer of 2015, and while there is some suspicion that snowy owl females may breed at that young an age, no one knows for sure, and the experts think maturity comes a bit later.

Hardscrabble and Dakota, on the other hand, are adults with proven nesting records, and Favret and Wells are at least three years old and possibly more. They have an awfully powerful magnet pulling them back to the north — to find a mate and a territory, and if the lemmings are abundant enough this summer, to start a new generation.